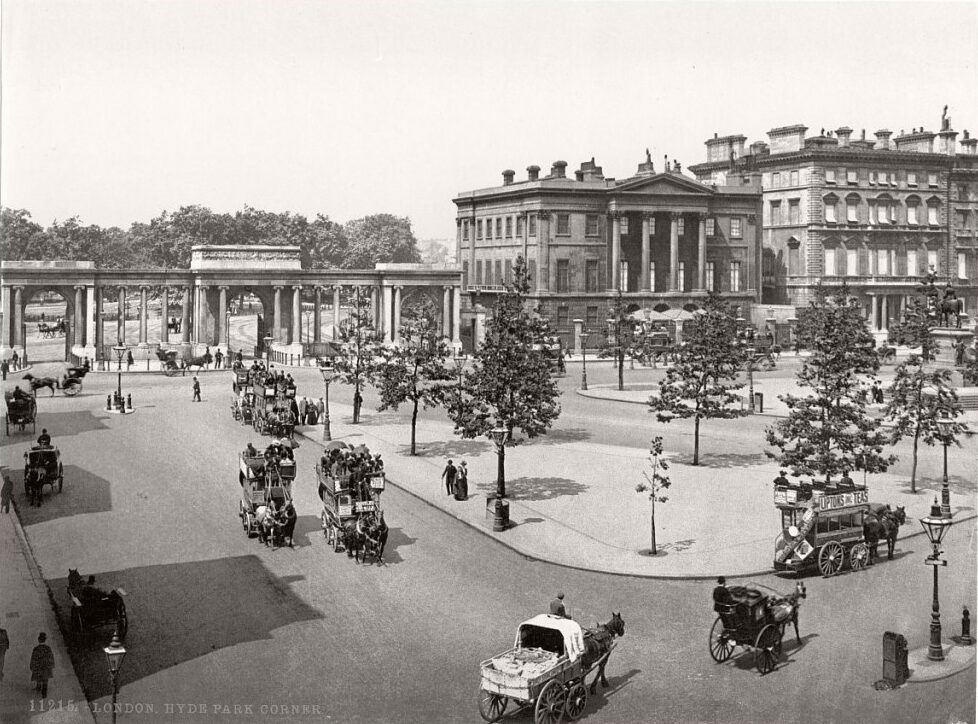

Nineteenth-century London, the proud heart of a vast British Empire, had become a political, cultural, and financial capital admired across the world. Queen Victoria ascended the throne in 1837 and remained there for the next sixty-four years. Her dignity, decorum, and strict moral standards shaped English society, which tried to follow her puritanical way of life. Yet behind the glittering façade of imperial modernity loomed a very different face of the metropolis riddled with poverty and prostitution.

Shadows of the Empire

In the east, the fearsome and repellent area of the East End spread relentlessly, with Whitechapel district at its core. Filthy, cramped streets housed more than 78,000 people living in severe poverty. Malnutrition and disease were so widespread that children had only a fifty-per-cent chance of surviving beyond the age of five. The local population consisted largely of the impoverished working class, employed in nearby factories and the docks. The area was also full of homeless, surviving in a state of chronic, crushing hardship.

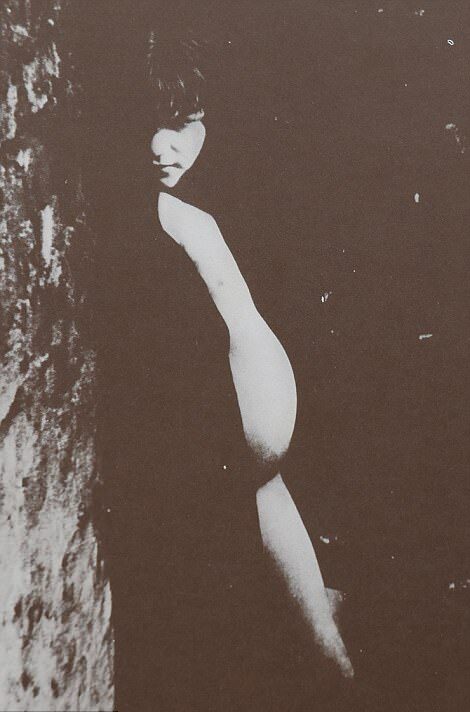

Another distinct group was the unusually large and conspicuous population of prostitutes. Despite strict Victorian morals, prostitution was legal and practised across all social classes. The country was so saturated with it that some sociologists saw it as the greatest evil eating away at the nation. In London’s slums the problem was especially striking. Labourers, desperate to escape the misery of their own lives, eagerly sought the company of local women who had been forced into sex work by sheer financial desperation.

Two Worlds of Women

Women in Victorian society occupied two entirely different spheres. Respectable young ladies preserved their virtue until marriage, and, once wed, their principal role was to serve as mothers and guardians of the domestic hearth. According to the teachings of the clergy, sex existed solely for procreation; any other form of intimacy, whether within marriage or outside it, was deemed improper.

Thus, a married woman living according to the official moral codes was not expected to engage in sex for her own gratification or her husband’s. Female sexuality was considered weak, dormant, or unnatural, and arousal was thought harmful to the delicate heart and nerves of the “fairer sex”. This angelic ideal did not extend to the lower classes, whose lives bore little resemblance to such fantasies. Consequently, upper-class men often sought from rough, straightforward working girls what they could not demand at home.

Hence the growing need for a “second category” of women – those whose role was simply to be objects of desire. Working-class women needed money to survive; gentlemen possessed it in abundance. Basic economics ensured that prostitution quickly became an officially condemned yet quietly accepted form of male recreation.

The Bastardy Clause

In 1834, Parliament passed the “Bastardy Clause”, stripping unmarried mothers and their children of any right to state relief. Forced through by groups opposed to premarital sex, the law also denied women – whether seduced with false promises of marriage or raped – any claim to financial support from the child’s father. As a result, men were effectively given a licence for consequence-free extramarital sex, while the entire burden of social and financial responsibility fell solely on the mothers. This feminisation of poverty fuelled both prostitution and infanticide, each becoming a grim reality of the era.

Factory Hardship

Most street prostitutes of London’s East End came from families in severe poverty, and more than half were orphans forced to navigate the brutality of the slums alone. The majority began their working lives in respectable employment. According to the 1851 census, women made up over 30 per cent of the labour force in East End factories, but the jobs available to them were among the harshest and worst paid.

Factory work meant six long days a week, with shifts of at least ten hours. Another parliamentary act passed in 1834 further worsened their situation by insisting that women should be treated the same as men in the workplace. Rather than increasing their pay to achieve that equality, the ruling simply allowed employers to mix both sexes on the same factory floors, making sexual harassment rife and assault common.

Women employed in female-only sewing workshops were spared harassment, but endured different hardships. Hand-sewing was carried out in stifling, overcrowded rooms with little natural light and almost no breaks. Employment was precarious, driven by fluctuations in demand.

During the spring–summer social season, the elite descended on London, and fashionable ladies delayed their dress orders until the last possible moment, for fear of choosing a style already deemed passé. Once orders were placed, they demanded almost immediate fulfilment, threatening cancellation. Seamstresses were forced into long periods of continuous labour, often without sleep or food. After the season ended came long periods with neither work nor income.

Domestic Exploitation

Domestic service, though the best paid of these forms of employment, was also the most gruelling. Servants worked a minimum of twelve hours a day, seven days a week, with one day off per month – if that. Sexual exploitation in wealthy households was rampant.

Recurring assaults and threats of dismissal for non-compliance by the head of the household, their sons, or senior servants were commonplace. Women who tried to speak up were often blamed for immorality, accused of seducing the men within the family, and promptly dismissed. A maid might lose her position for almost anything: a broken plate, a missing spoon, or overhearing the wrong conversation.

Other common occupations for Victorian women included shop work, laundry, and milk delivery. Whichever of the above “respectable” forms of employment they chose, the bleak reality remained the same: none paid enough to support a family. Most women struggled to support even themselves.

Secret Lives

The loss of virginity – whether consensual or not – destroyed a young woman’s prospects of a respectable marriage. Under strict Victorian morality, she was immediately pushed to the margins of society.

Given the constant risk of harassment and assault at work, it is little wonder so many women who lost their “treasured asset” resorted to secret prostitution. Determined to maintain a veneer of innocence, they kept their day jobs while selling sex under cover of darkness.

Once the truth inevitably surfaced, they were dismissed from the workplace for immoral conduct. With their reputations ruined and no chance of new employment, many had no choice but to enter the profession openly.

In October 1888, London’s police estimated that more than 1,200 women were working as prostitutes in Whitechapel district alone – a figure we now know was severely understated, as it excluded married women. Extreme poverty forced hundreds of wives of costermongers, pedlars, and small tradesmen into covert prostitution. Their husbands, unable to earn enough themselves, often encouraged or even managed their wives’ work and supplied them with clients. This hidden form of prostitution was a crucial means of survival for many families.

Child Prostitution

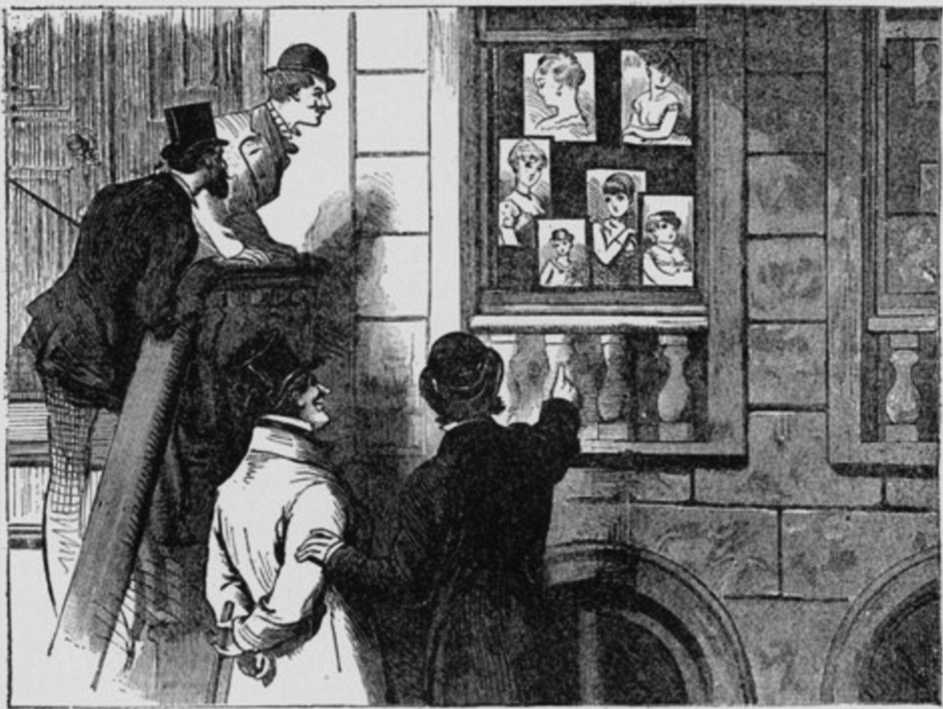

The average age of a London prostitute was around twenty, though many began far earlier. Until 1885, the age of consent was only thirteen. Brothels specialising in very young girls were popular among upper-class clients who didn’t mind paying handsomely for the “freshness of the experience” and the safety of virgins being free from venereal disease.

Parents sold their daughters’ innocence out of abject poverty and addiction to gin or opium. The daughters of prostitutes entered the trade even earlier, assisting with domestic chores in brothels as very young children and beginning the work themselves as soon as they turned thirteen.

In 1885, journalist W. T. Stead published a series of shocking articles in the Pall Mall Gazette under the title The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon, exposing how easily he could purchase a thirteen-year-old girl in the East End for £5 (around £330 today). This sum covered a medical examination confirming her virginity, a fee for the intermediary, and payment to the parents.

The doctor recommended using chloroform to ensure she was unconscious during the rape. The parents accepted the whole arrangement with chilling indifference. The intermediary washed and dressed the child, then sent her to bid farewell to her parents. Her mother was too drunk to recognise her, and her father remained unmoved.

Stead’s articles caused public uproar and led to the age of consent being raised to sixteen later that year. The same act, however, criminalised male homosexuality – a status that persisted until the 1960s.

Life, Disease and Death

Prostitutes working the streets of East End owned nothing beyond the clothes they wore. Their day’s earnings afforded them only a little food, some alcohol, and a bed for the night. Reports from the period describe women so desperate that they sold themselves for three pence (less than a pound today) or even a stale loaf of bread.

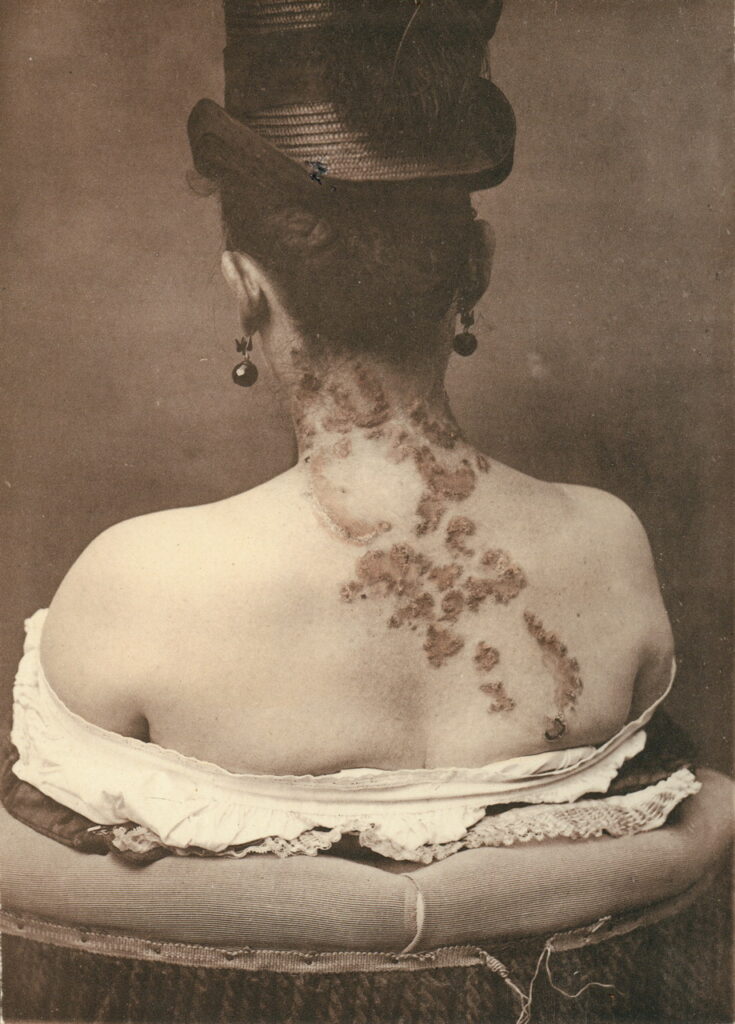

The ravages of their lifestyle meant that many women in their twenties looked twice their age. Opium and alcohol were common escapes, further straining their limited resources. Syphilis was rampant, devastating both prostitutes and their clients. Nine out of ten women in the trade died prematurely from various illnesses.

Venereal disease became such a national crisis that a military report cited it as a primary cause of the army’s declining strength. With no contraception available, illegal abortions were routine. Performed in alleys or filthy basements, they often resulted in catastrophic infections or fatal haemorrhages. Many women died after ingesting poisonous substances intended to end unwanted pregnancies. Only a few reached hospitals; most simply perished on the streets. Suicide and attempted suicide were all too common.

Those who avoided addiction and disease occasionally saved enough to start small businesses – cafés or lodging-houses were popular choices – and a select few, through beauty and luck, became the kept mistresses of wealthy men.

Lodging Houses

East End in the late nineteenth century had more than 230 lodging houses, often the only shelter available to the area’s destitute residents. Neighbourhoods around Flower and Dean Street and Dorset Street in Whitechapel were infamous for cheap beds and dangerous occupants.

By law, men’s and women’s dormitories were meant to be separate, but this rule was rarely enforced. Most houses were owned by middle-class investors living far from the slums, while day-to-day management fell to hired wardens – many with criminal pasts. A bribe could buy silence on almost anything.

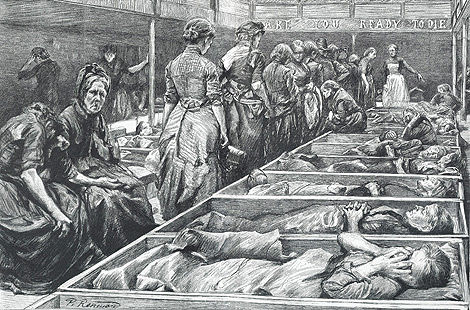

As long as residents could pay four pence for a bed, they were admitted – thieves, vagrants, sex workers, and the desperately ill all crowded together. Beds were narrow wooden coffins laid side by side on the floor, lined with hay and filthy blankets swarming with vermin. Communal kitchens were stocked with food bought, begged, or stolen during the day. Each night, more than 8,500 men, women, and children sought refuge in these establishments.

The sick lay feverish beside children and intoxicated prostitutes. Brutalised clientele did not hold back from theft or assault; violence and brawls were part of the daily routine. Few of the original nineteenth-century lodging houses survive today; one that does is the Providence Row Night Refuge and Convent, where Mary Kelly – later murdered by Jack the Ripper – often sought shelter.

Modern Whitechapel

By the late nineteenth century, the slums surrounding Whitechapel Road were gradually demolished. Magdalene asylums were established to help women on the brink of destitution, aiming to rehabilitate them and return them to society. Over time, however, these institutions grew increasingly punitive. Women were subjected to harsh labour, enforced silence, and long periods of prayer and fasting. Remarkably, the last Magdalene asylum in Britain closed as late as 1996.

Prostitution has not vanished from the East End. The modern Flower and Dean estate – built on the site of the old Victorian lodging houses – is a warren of red-brick blocks, narrow lanes, and blind corners. Nearby Commercial Street, a busy route linking the City of London to the nightlife around Brick Lane, remains a well-known red-light area. Prostitutes solicit openly on almost every corner, and Flower and Dean’s secluded alleyways are frequently used to service clients. Local residents, many of them devout Muslims, have repeatedly appealed for protection of their children, who play among discarded needles and used condoms.

It is a bleak and bitter irony that, in the very streets where Victorian women suffered, starved, and died in filth, modern women still sell sex today. It exposes a cruel continuity: generations change, but the conditions trapping women in the vicious cycles of patriarchal society remain hauntingly familiar.

Discover more from London Macabre

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.