Sir Adam Newton, the first owner of Charlton House, was an undeniably ambitious man: swift rise at court, well-placed connections, and a remarkable gift for turning royal proximity into privilege. His marked talents allowed him to secure positions that other sons of ordinary Scottish bakers could only dream of.

A False Priest, a Royal Tutor

Newton’s precise birthdate is unknown, but around 1590 he was residing in France – illicitly posing as a priest while teaching at the Collège de Saint-Maixent. Around 1600, as a polished and well-educated tutor, he came back to Scotland and was appointed at Stirling Castle as a private instructor to Prince Henry, eldest son of James I. When the crowns of England, Scotland and Ireland were united in 1603, Newton followed the royal household to London and was swiftly naturalised as an English citizen. The king, whether grateful for his son’s education or simply unwilling to lose an apparently exceptional tutor, agreed to fund the extravagant cost of building Newton a new residence near Greenwich Palace.

A Baker’s Son with a Courtier’s Hunger

In 1607, Newton purchased the Charlton estate from Sir James Erskine for £4,500 (roughly £680,000 today). As a person of humble origins, with only a few years of service at court, he acquired such a vast sum through skilful manoeuvres. The king paid handsomely for his son’s schooling, and Newton’s role perhaps came with opportunities more lucrative than his official position suggested.

Moreover, teaching a royal was not his only responsibility at the time. In 1605, despite lacking any clerical orders, he secured the Deanery of Durham through his influence with James I – a role in which any genuine duties were delegated to a proxy, while the income flowed directly to his pocket. His private life was equally financially advantageous. In 1605 he married Catherine Puckering, the youngest daughter of Sir John Puckering, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal under Elizabeth I.

One might have expected his fortunes to falter after Prince Henry died in 1612, just after Charlton House was completed. Instead, Newton’s position only strengthened. He became treasurer of the household of the new heir, Prince Charles, and remained in this highly profitable post for the rest of his life. Meanwhile, Lady Newton died in 1618, leaving Sir Adam with four children: William, who died young; Henry, who later adopted his mother’s surname; and Elizabeth and Jane, who took their husbands’ names. This explains why the Newton line disappears from later records.

The Last Ambitions

In 1620, Newton purchased a baronetcy – likely funded by selling the now-superfluous Deanery of Durham. The title, created only in 1611 by James I, required candidates to maintain thirty soldiers for three years at a cost of £1,095 (about £275,000 today). It was not a noble rank, merely an expensive and well-branded privilege and a fancy title.

After Charles I’s accession, Newton secured yet more influence: he became secretary to the royal council, and in 1628 was appointed Secretary of the Welsh Marches, a role worth another £2,000 a year. Two years later, having reached the height of his career, he died in January 1630. His executors honoured his final wish by restoring the parish church of St Luke in Charlton, which stands there to this day.

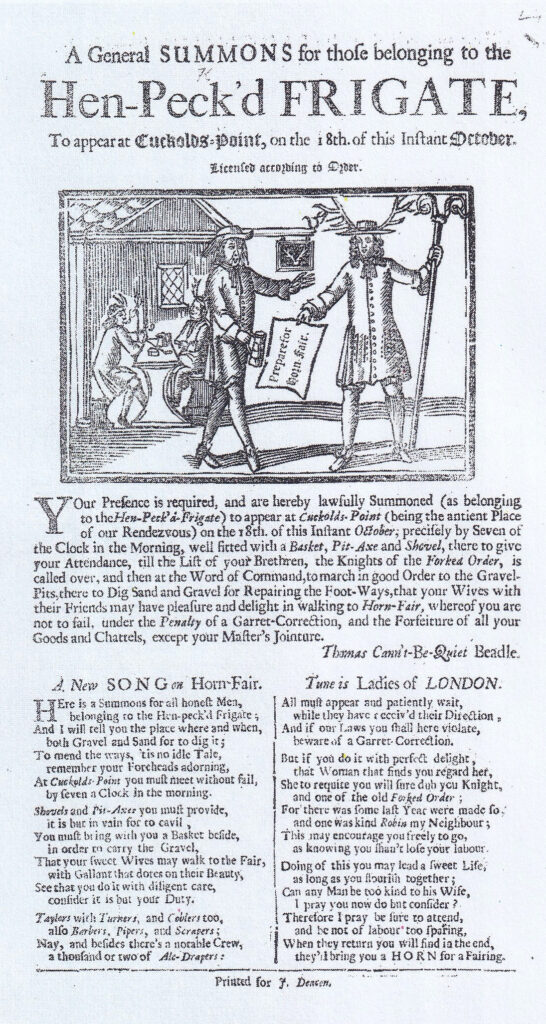

The Fair of Wild Revels

To fully appreciate how the construction of the distinguished Charlton House subdued and transformed the once uninhibited freedom of the locals, one must first understand the character of this riverside farming settlement before Sir Adam Newton ever arrived.

In the thirteenth century, King Henry III granted Charlton an annual market and fair. For centuries thereafter, the celebrations of St Luke’s Day, held on 18 October, carried to London tales of a particularly chaotic and earthy revel. The event became known as the Horn Fair, owing to the enormous quantities of horns, drinking vessels, and other horn-made wares brought there for sale. Several theories exist regarding the origin of the name, but the most plausible appears to be a reference to St Luke’s traditional emblem – the horned ox depicted in early iconography.

At first, the fair was held on an open meadow. As the settlement grew, however, the meadow disappeared beneath the village green opposite the church, just steps away from the Charlton House. By the reign of Charles II, the event had taken on the character of an unrestrained, rowdy carnival. Visitors from London would cross the river by boat, dressed as kings, queens, millers, or adorned with great curling horns upon their heads. Men dressed and adorned as women formed a rackety procession, marching round the church and the fair, honouring their patron saint with loud cries, singing and the incessant blaring of ram’s horns.

A Village Tamed

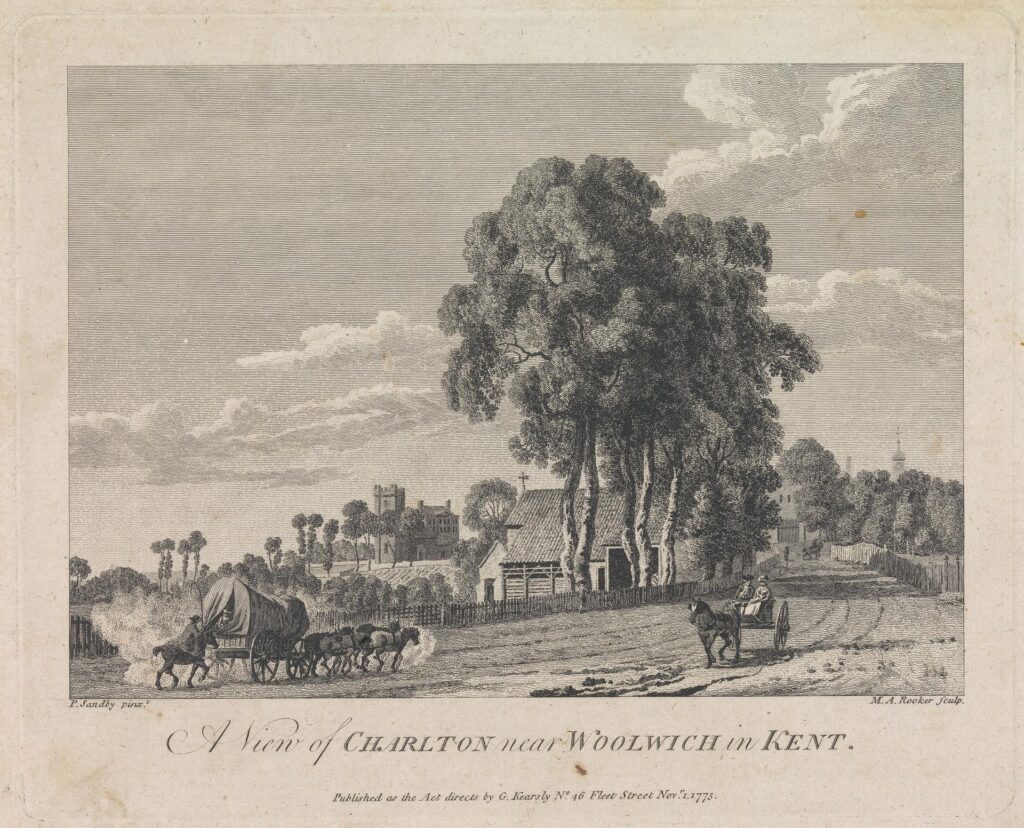

Perhaps it came as no surprise that by the mid-seventeenth century, the fair was banned – its bawdy excesses evidently too offensive for the refined sensibilities of those occupying nearby Charlton House. Thus, while the estate did not give rise to the village itself, its presence gradually reshaped the spirit of the place. The parish church and village green, together with the manorial residence, formed a new centre for the community. Newton’s connections at court brought both pride and a certain restraint to the villagers.

For the next hundred years, the area remained a charming hilltop village between Greenwich and Woolwich, overlooking the Thames valley, yet its wild and carefree character slowly faded. Even the local wildlife was no longer free from interference. According to The Gentleman’s Magazine, in 1734 a colossal eagle – its wingspan said to exceed three meters – was captured in Charlton. The bird was immediately claimed by the then-owner of Charlton House, but before long the royal falconer demanded it as a creature rightfully belonging to the Crown. The eagle was duly removed to court. What became of it afterwards is unrecorded – one can only hope it did not spend the rest of its life in captivity.

A Jacobean Masterpiece

Charlton House, completed in 1612 after five years of intense construction, remains one of London’s finest surviving examples of Jacobean architecture. It endured both the Blitz and the ravenous expansion of the modern city. Even at the time of its creation, it stood apart from the capital’s architecture: strikingly elegant yet modern, equipped with a rudimentary plumbing system and running water drawn from a nearby well.

In Newton’s era, its appearance must have been a stark contrast to the austere, functional buildings of the preceding age. Inside, many of the original elements commissioned by the house’s first owner have survived. Visitors may still admire the original ceilings, wooden panelling, and splendid marble fireplaces. The main staircase is also original, fashioned from heavy oak beams, with a rectangular recess and a strongly profiled handrail and balustrade.

The Grounds and Gardens

The grounds surrounding the house once extended over some 28 hectares. Part of them now form the public Charlton Park. In the garden grows a venerable mulberry tree, planted by order of King James I as part of his ambitious plan to establish a British silk industry. Unfortunately, the black variety chosen rather than the white preferred by silkworms doomed the project to failure. Near the mulberry stands a pavilion, now a Grade I listed building. In the interwar period it was converted into public lavatories, but it has since been painstakingly restored. The gardens also retain old plane trees, along with remnants of former kitchen and flower gardens.

For those not swayed by the gardens and interiors alone, Charlton House offers darker delights: macabre and unexplained stories connected to its former owners and their servants.

The Ghost of the Grey Lady

Charlton House is widely regarded as one of the most haunted locations in London. Over the centuries, numerous residents of the house have left behind traces of their presence that have undoubtedly contributed to the many reports of paranormal activity occurring in various parts of the residence.

The most famous and fearsome apparition associated with Charlton House is the Grey Lady. Museum staff have reported seeing her on multiple occasions, wandering through the gardens or the corridors in broad daylight. Witnesses claim that the spectre is always cradling a bundle resembling a wrapped infant.

Tradition holds that she is the ghost of one of the house’s servants from the Jacobean era. At that time, the domestic staff – particularly female maids – typically lived in the attics or upper floors, while male servants, including footmen and coachmen, slept on the ground floor close to the kitchens and stables. Both groups were strictly segregated from the family living quarters, reflecting the rigid social hierarchies of the period.

Viewed in this context, the story of the Grey Lady fits perfectly with the unsettling atmosphere that pervades the attic rooms. A strange, oppressive sensation overwhelms most who enter, and many of Charlton House’s staff prefer not to venture there alone. The lower ground floor and cellars are considered even more forbidding, with some individuals refusing to descend into them even in company.

The Bodies in the Fireplaces

The tale gained further weight when, during restoration work, a mummified infant was discovered within an old fireplace. Notably, this discovery reportedly triggered an increase in paranormal activity. Staff began reporting the mysterious disappearance of their belongings, only to find them later in entirely different parts of the house. It is now believed that the child was most likely the deceased offspring of one of the servants, born out of wedlock and hidden to avoid scandal.

Speculation abounds regarding the child’s paternity. Some suggest the father may have been one of the male servants, which might explain the oppressive atmosphere in the house’s lower floor. Others claim the infant could have been the result of an illicit affair – or even coercion – involving a member of the aristocratic family, who perhaps commanded the girl to conceal the child. Questions also remain as to whether the infant died a natural death or if someone contributed to its demise.

Curiously, another fireplace in the house is linked to a different macabre story. Within one of the house’s chimneys, the body of a young boy was reportedly discovered. He is thought to have been an apprentice chimney sweep who became trapped in the flue and perished from starvation, unable to escape.

Nocturnal Investigations

For those seeking a more intense experience or a first-hand account of these extraordinary claims, Charlton House offers nocturnal paranormal investigations. Participants spend the entire night within the residence, using Ouija boards, dowsing rods, and other devices in attempts to communicate with the house’s spirits. Many accounts describe strong emotional reactions and successful attempts at contact with the Grey Lady, who is said to recount the tale of her endless search for her deceased child.

The Abduction of Jane Puckering

A truly gothic and blood-chilling story is linked to Charlton House, that of Jane Puckering. As the sole surviving child of Sir Thomas Puckering, who died in 1637, the underage Jane stood to inherit lands worth at least £3,000 per year (roughly £460,000 in today’s money) upon reaching the age of twenty-one.

On 26 September 1649, the nineteen-year-old Jane was strolling through Greenwich Park with her cousin, Mrs Smith, when she was suddenly attacked by a group of men armed with swords and pistols. Ignoring the desperate screams of Jane, her companion, and two servants, the assailants forced her onto a horse and abducted her.

The Marriage of Desperation

Twice Jane attempted to escape, hoping to throw herself from the galloping horse, but to no avail. The kidnappers carried her all the way to Erith, where she was taken aboard a ship. It was only then, terrified and bewildered, that she first saw the organiser of the attack – Joseph Welsh. Her considerable fortune made her an exceptionally valuable prize, which Welsh intended to seize without ceremony. It was later claimed that Joseph had the assistance of a royal agent and the king’s mistress, Jane Whorwood. While Welsh’s motives are clear, Whorwood’s desires remain a mystery to this day. Her involvement, however, hints at a far deeper and more intricate intrigue, now lost to the shadows of history.

The ship set sail for Margate, and thence to Flanders. Once there, Jane was held captive for many months – first in Welsh’s hideout, and later in an English convent. Eventually, broken by fear and desperation, she agreed to marry her captor in exchange for the promise of reconciliation with her family and a return to England.

The Unpunished and the Lost

As soon as she regained her freedom and crossed the threshold of Charlton House, she immediately initiated proceedings to have the marriage annulled. The case was heard by Lord Chief Justice Rolles and commissioners appointed by Parliament. In July 1651, at the Maidstone trial, Joseph Welsh and his accomplices were charged with unlawful abduction – a crime punishable by death at the time. Yet Jane never saw justice served, nor a happy resolution to her ordeal. There is no record of Welsh ever facing any punishment; he managed to flee and evade the law.

Perhaps fearing further abductions and seeking to protect her fortune, Jane soon married her cousin, becoming Lady Bale. She died within a year of the wedding, in childbirth. Her tragic story, and the criminal case against Welsh and his accomplices, died with her last breath.

The Childless Baronet

Henry Newton, who adopted his mother’s surname to become Sir Henry Puckering, inherited the estate of his uncle, Thomas Puckering, in 1654, following the tragic death of Jane. A staunch Royalist, Henry fled Charlton during the English Civil War. In 1659, he decided to sell the residence to Sir William Ducie, who lived there until his death in 1679.

Ducie’s heirs subsequently sold Charlton House in 1680 to the baronet Sir William Langhorne, a wealthy merchant of the East India Company and long-serving Governor of Madras. Langhorne amassed a vast fortune, blending legitimate trade with the Levant with illicit dealings conducted discreetly during his time in India. Upon returning to London, he chose Charlton as a tranquil retreat for his retirement.

Marriages and Misfortune

Although he enjoyed the company of women, Langhorne never fathered an heir. By the time he returned to England, aged 68, he was desperate to find a suitable bride. In 1699 he married the much younger Grace Chaworth, a widowed viscountess, making him one of the richest men in the country. The union, however, was brief: Grace died on 15 February 1700, less than a year after the wedding.

Still mourning the absence of children, Langhorne, after fourteen years of solitude and now in his eighties, remarried on 16 October 1714 – this time to the merely seventeen-year-old Mary Aston. Yet he enjoyed neither the marriage nor the prospect of an heir for long: he died just two months later, on 26 February 1715, aged 85. His young wife bore no child despite numerous attempts, leaving Langhorne’s line unfulfilled. With his death, his baronetcy became extinct.

The Sighing Ghost of Langhorne

Sir William was interred in the nearby parish church at Charlton, yet, local lore claims, his restless spirit still roams the rooms and corridors of Charlton House, forever seeking the young lady with whom he might finally sire the heir he so long desired. Witnesses speak of bedroom door handles turning by themselves, sudden movements of objects, mysterious sighs, and chilling drafts of air, particularly in the Saloon and the Long Gallery – the baronet’s favourite rooms on the upper floor.

After his death, the estate passed to more distant nephews, who, in a cruel twist of fate, all died childless. Ultimately, the fortune fell to an even more distant relative of the Langhorne line, Mrs Margaret Maryon. She inaugurated the long stewardship of the Maryon-Wilson family over Charlton House, which they maintained until 1925.

The Maryon-Wilson Legacy

During World War I, as London’s hospitals began to buckle under the influx of wounded soldiers returning from the front, Sir Spencer and Lady Maryon-Wilson offered most of the house to create an auxiliary hospital. The facility operated from October 1918 to April 1919, treating approximately 160–168 patients during that time. It had 70 beds and was affiliated with the main Brook War Hospital. In 1925, the owners decided to sell Charlton House along with its adjoining lands to the Metropolitan Borough of Greenwich, as the family had no plans to return.

Today, the residence serves as a community centre, a venue for weddings, and an event space. It houses the offices of the Greenwich Heritage Centre, Charlton House Library, and a café, while the gardens and historic rooms on the upper floors remain open to the public free of charge.

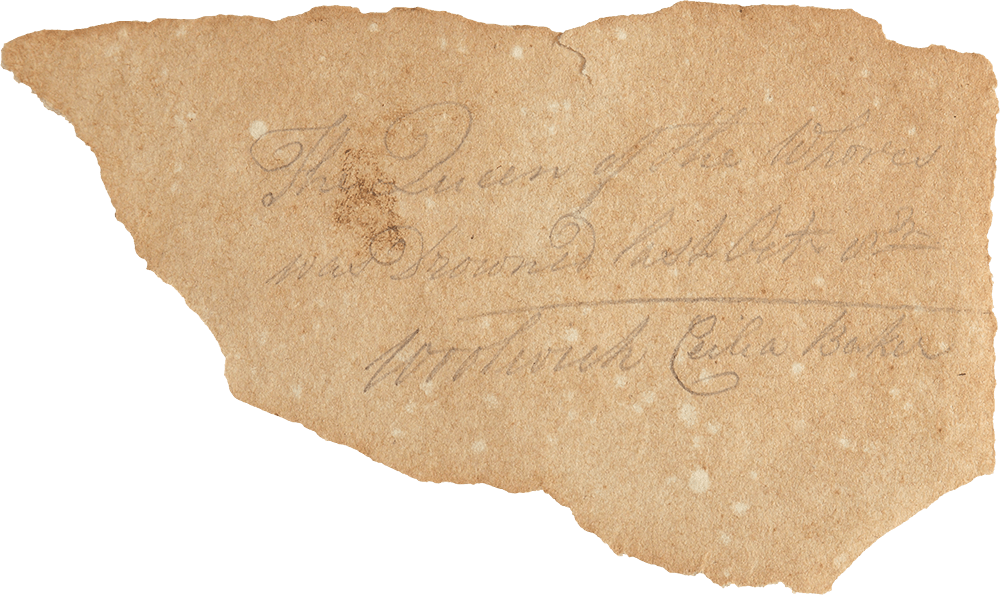

A Peculiar Note from the Past

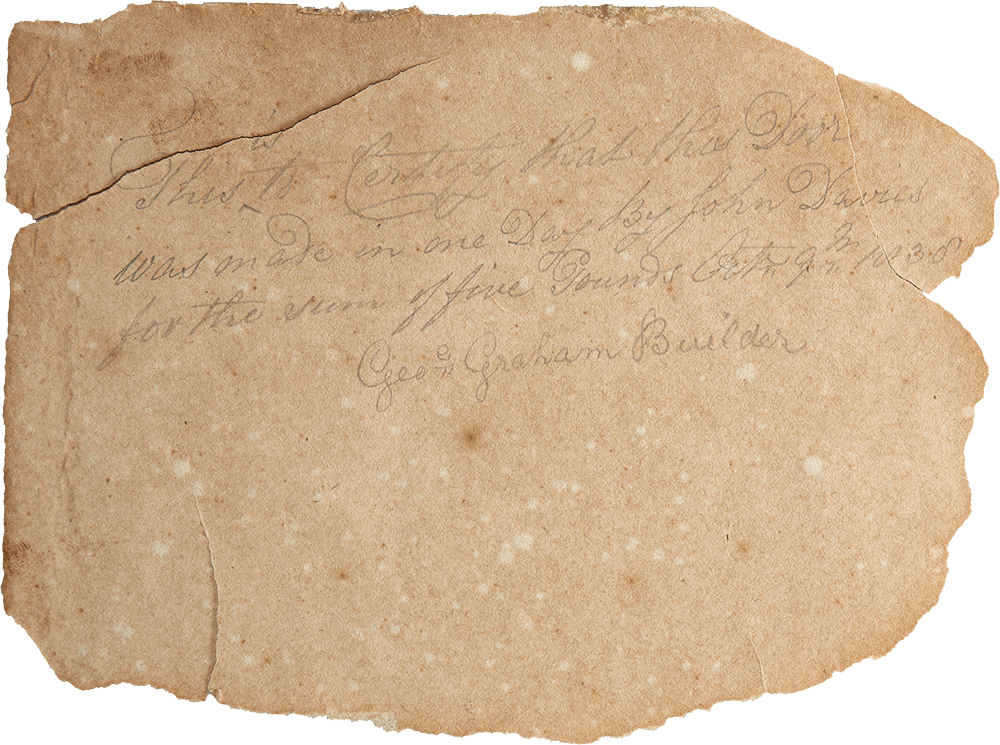

During one of the many recent restorations of Charlton House, two scraps of paper were discovered within a set of doors crafted in 1834, deliberately concealed by the carpenter who had built them. The first note reveals that his name was John Davies, that it took him a single day to make the doors, that he was paid five pounds, and that his employer was the firm George Graham & Son of Woolwich. On the second, separate piece of paper, John wrote: “The queen of the whores was drowned last October 10th. Woolwich Celia Baker.”

Despite the efforts of local historians and the Royal Greenwich Heritage Trust, the identity of the mysterious Celia Baker remains unresolved. This peculiar pair of notes forms a kind of time capsule – the gesture of a working-class man perhaps wishing that future generations might glimpse the lives of those who never had a chance of appearing in history books. While the families who lived in Charlton House over the years can be traced and arranged into a clear chronology, people like John Davies – indispensable to the running of the house – remained forever anonymous.

The Forgotten Lives of the Manor

The use of a specific name and the sensational tone of the second note suggests that Celia Baker was indeed a figure known locally in Woolwich or Charlton. The scandalous epithet employed by John indicates that the nickname circulated within the working-class community and would have been widely understood. Yet Celia left no trace beyond this single scrap of paper. She may have run a brothel or been a woman of such dubious reputation that she provoked scandal, outrage, and gossip – perhaps even bringing about her own death by drowning.

The note preserved in the doors captures a striking, dramatic moment in the life of a long-forgotten community – a moment John Davies deemed worth recording. It is a fragment of the history of those who lived, laboured, and died alongside famous historical figures, yet without hope of having their existence remembered in any other way.

Discover more from London Macabre

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.