A late Victorian enclave for the well-to-do middle classes, Notting Hill began to crumble in the wake of the First World War. Over the following decades, the area would become known across London for the exploitative subletting practice later known as Rachmanism.

With the arrival of the new century and the shortages brought by war, many wealthy families abandoned the Ladbroke Estate and moved away from the capital. Domestic staff were dismissed, grand residences lost their market appeal, and the era of palatial splendour slipped quietly into history. Luftwaffe air raids during the 1940s destroyed much of the district’s older buildings, leaving scars that would linger for decades. In the aftermath, Notting Hill gradually transformed into a neglected quarter of damaged houses and cheap hostels, inhabited by prostitutes, gangsters, and murderers (including the infamous John Christie).

The early 1950s marked the beginning of rapid social change. The replacement of the former slums of Notting Dale with a council housing estate, intensified immigration from the Caribbean, and the radicalisation of post-war social attitudes were just some of the key developments shaping the district’s future character. Out of this shortage, fear, and neglect emerged also one of post-war London’s most notorious figures: Peter Perec Rachman.

Empire in Ruins

Britain’s involvement in the Second World War created a desperate housing crisis in a bomb-ravaged London. At the same time, the deaths of large numbers of young men on the front led to a severe labour shortage across key sectors of the economy, pushing the country to the brink of collapse. In response, the government issued regulations facilitating the employment of people from Britain’s colonies, particularly the West Indies – a region of more than twenty Caribbean islands, including Jamaica, Barbados, and Trinidad. The name West Indies dates back to the era of early colonisation, used by the British to distinguish their western imperial possessions from those in South Asia, known as the East Indies.

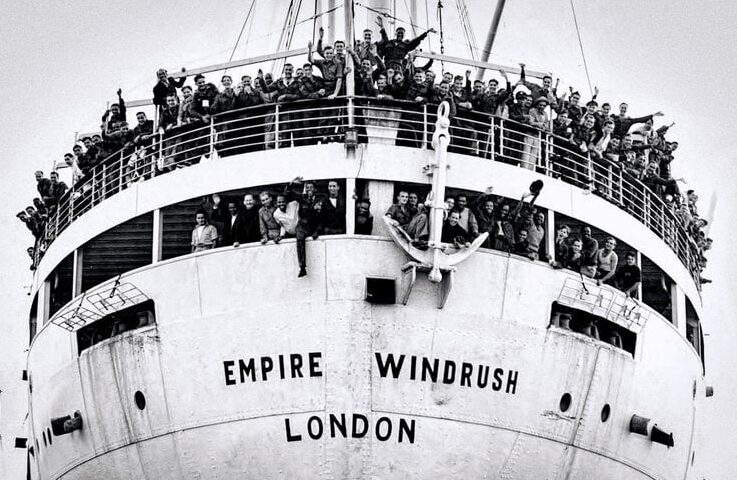

The Windrush Years

Between 1948 and 1970, over half a million people migrated from the Caribbean to Britain. Supporters of the move, including the King and majority of politicians, expected it to be welcomed by the English, both because the 1948 British Nationality Act had conferred citizenship on colonial subjects and because West Indian workers were urgently needed in public transport, hospitals, and the postal service.

People came for a variety of reasons. Some sought new professional opportunities and a more secure future for their children. Others hoped to save money before returning home. Many were former soldiers who had fought for Britain during the war and, once hostilities had ended, chose to remain in Europe.

The Empire Windrush ship, which arrived in London on 22 June 1948 carrying several hundred hopeful migrants, soon became an enduring symbol of this post-war mass relocation. As the first ship to arrive following the Nationality Act, its name came to represent the generation of Caribbean arrivals who continued to settle in Britain until the 1970s – now known collectively as the Windrush generation.

A Hostile Welcome

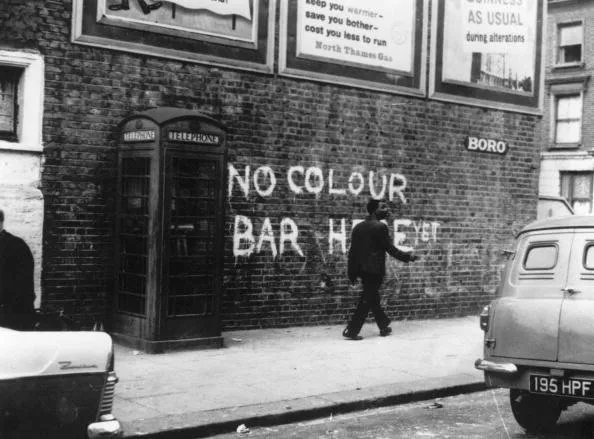

The welcome extended to the immigrants by London’s residents was far removed from the encouraging tone adopted by the British government and the King. Due to their skin colour and status, people arriving from the Caribbean were routinely refused accommodation or employment in wealthier areas of the city. A common sight on London streets was rental notices bearing the chilling disclaimer: “No Blacks, No Irish, No Dogs.”

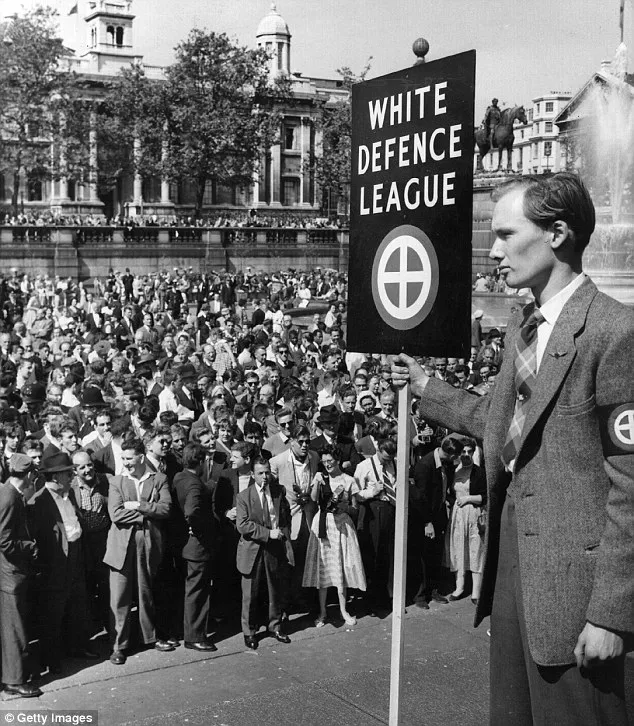

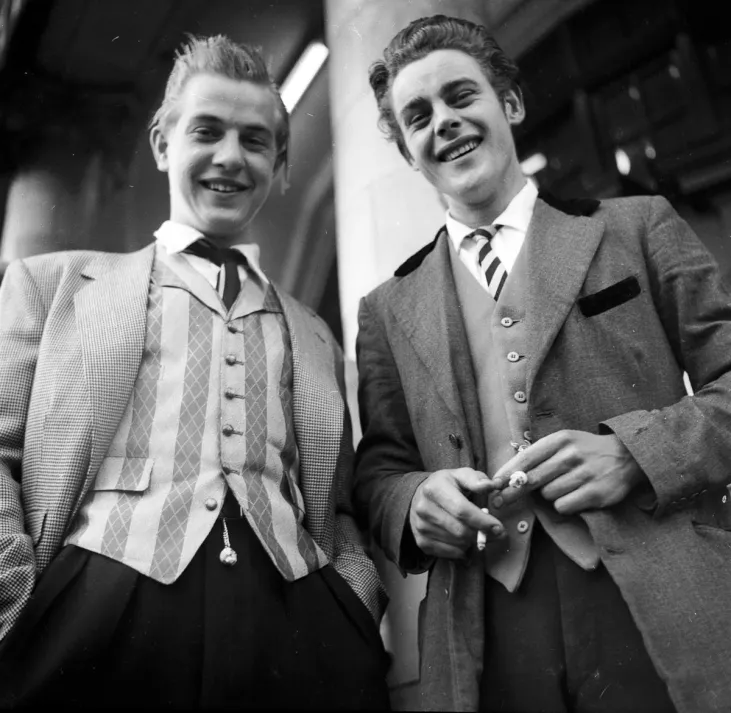

The radicalisation of social attitudes was also reflected in the emergence of racist and fascist organisations. Among the most notorious was the White Defence League, a far-right group led by Colin Jordan. Its members urged Britons to oppose Black immigration with slogans such as “Keep Britain White.” This ideology of hatred soon found an audience among young, uneducated working-class men known as Teddy Boys.

Youth and Violence

The Teddy Boys began as a largely harmless youth subculture, which gained particular popularity in the 1950s. Members adopted clothing inspired by Edwardian-era dandies, hence the name “Teddy,” derived from the diminutive of Edward. What started as a form of non-conformism and rebellion against grim post-war realities gradually absorbed the rhetoric of right-wing movements. Before long, Teddy Boys began forming rival gangs. Fuelled by racist ideology, the aggression of these young proletarians quickly manifested itself in immigrant-heavy Notting Hill. Black residents living around Bramley Road became the proverbial scapegoats for London’s rebelious youth.

Five Days of Fire

In the summer of 1958, the simmering tension in Notting Hill finally erupted into five days of street violence. Brutal clashes broke out between the Caribbean minority and white residents of the district, composed largely of members of the White Defence League, the Union Movement, and Teddy Boy gangs.

A mob of over four hundred white attackers assaulted and vandalised homes in the vicinity of Bramley Road. The Metropolitan Police arrested around 140 people – primarily white youths, but also Black residents detained for possession of weapons. Today, the difficult history of the West Indies community in London is commemorated by a Caribbean cultural festival held since 1966. The famous Notting Hill Carnival draws hundreds of thousands of visitors from around the world each year.

The Windrush Scandal

The struggles of the Windrush generation resurfaced in 2018 as a national scandal, exposing the shocking consequences of Britain’s inadequate immigration policies. Many people who had arrived legally between 1948 and 1973, often as children and without needing documents, had lived, worked, and attended school for decades believing themselves to be British. Yet changes to immigration law, combined with administrative failings and systemic racism, meant some were retroactively treated as illegal immigrants – denied medical care, benefits, and housing, threatened with deportation, detained, or even removed from the country.

Despite warnings from caseworkers and MPs as early as 2013, the Home Office failed to act, allowing thousands to be wrongly targeted. By April 2018, Parliament confronted the crisis, dubbed by the press the Windrush Scandal, exposing the human cost of decades of neglect and official oversight.

The Birth of Rachmanism

Nationalist sentiments and the country’s dire economic situation in the 1950s gave rise to another phenomenon rooted in racism: Rachmanism. The term refers to the extreme exploitation of residential properties and the intimidation of tenants by landlords. It derives from the surname of Peter Perec Rachman, a notorious slum landlord operating in the post-war Notting Hill.

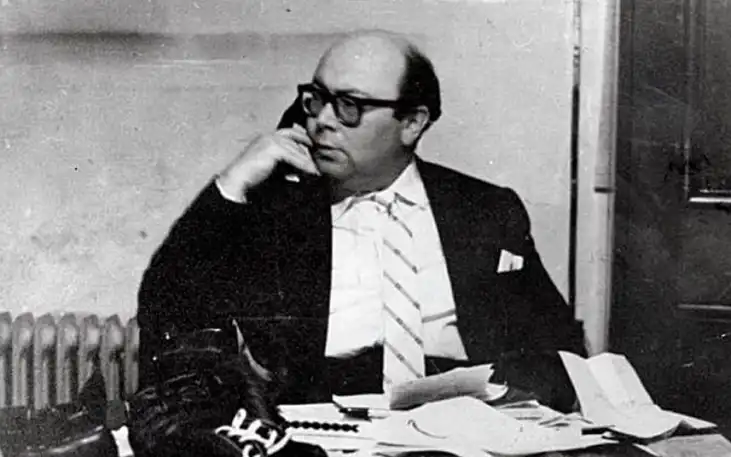

Rachman arrived in England after the Second World War as a refugee of Polish origin (born in Lviv in 1919, when the city still lay within Polish territory). He began his career at an estate agency in Shepherd’s Bush, but soon abandoned the position and established his own business, capitalising on the housing shortage. His agency, renowned for letting rooms at lightning speed, was based at 91/3 Westbourne Grove.

Fully aware of the precarious position of Black immigrants in London, Rachman skilfully exploited racist sentiments to build his empire of substandard lodgings for discriminated tenants. From 1957 onwards, aided by numerous loans, he acquired several terraced houses around Notting Hill – many of them still in a deplorable condition since the war.

Profit Through Terror

Rachman’s “business model” was based on extracting the maximum possible profit from his properties. His first step after purchasing a building was therefore to remove the existing tenants. He would initially offer residents a sum of money in exchange for relinquishing their tenancy rights. If that failed, their lives were turned into a waking nightmare of sleepless nights, accompanied by deafening music and the aggressive behaviour of planted neighbours.

In other cases, his men cut off electricity or water supplies, forced door locks, or destroyed shared lavatories. The strategy proved brutally effective. Vacated flats were then subdivided into single rooms and let to new tenants at exorbitant rents. His most frequent clients were those with nowhere else to go, unable to find better accommodation, leaving them vulnerable to his exploitation. Charging about £5 a week for a single room (roughly £76 today), his business rapidly turned into a goldmine.

A Fatal Loophole

Ironically, the British government itself contributed to the spread of Rachmanism. In July 1957, new legislation allowed landlords to set rents without restriction. This Conservative directive was intended to encourage the renovation of housing stock in the bomb-damaged capital. Property owners wishing to raise rents were, in theory, expected to carry out necessary repairs and modernisations, thereby reducing the number of abandoned and uninhabitable houses.

In practice, the Act led to drastic and unjustified rent increases across London. The new regulations resulted in over 200 eviction notices being issued in a single night. Existing tenants were forced out, clearing the way for figures like Rachman to repopulate the dilapidated buildings with desperate immigrants.

An Expanding Empire

The core of Rachman’s operations lay around Powis Square, Hedgegate Court, and Colville Road. Flats in the tenement buildings there were squalid, impossibly filthy, and generally unfit for human habitation. They became the first – and most infamous – slum within his growing empire. After acquiring the majority of houses on these streets, Perec expanded his influence to nearby locations including St Stephen’s Gardens, Powis Gardens, Powis Terrace, and Colville Terrace. He also owned number 90 on Lancaster Road.

Rooms of Desperation

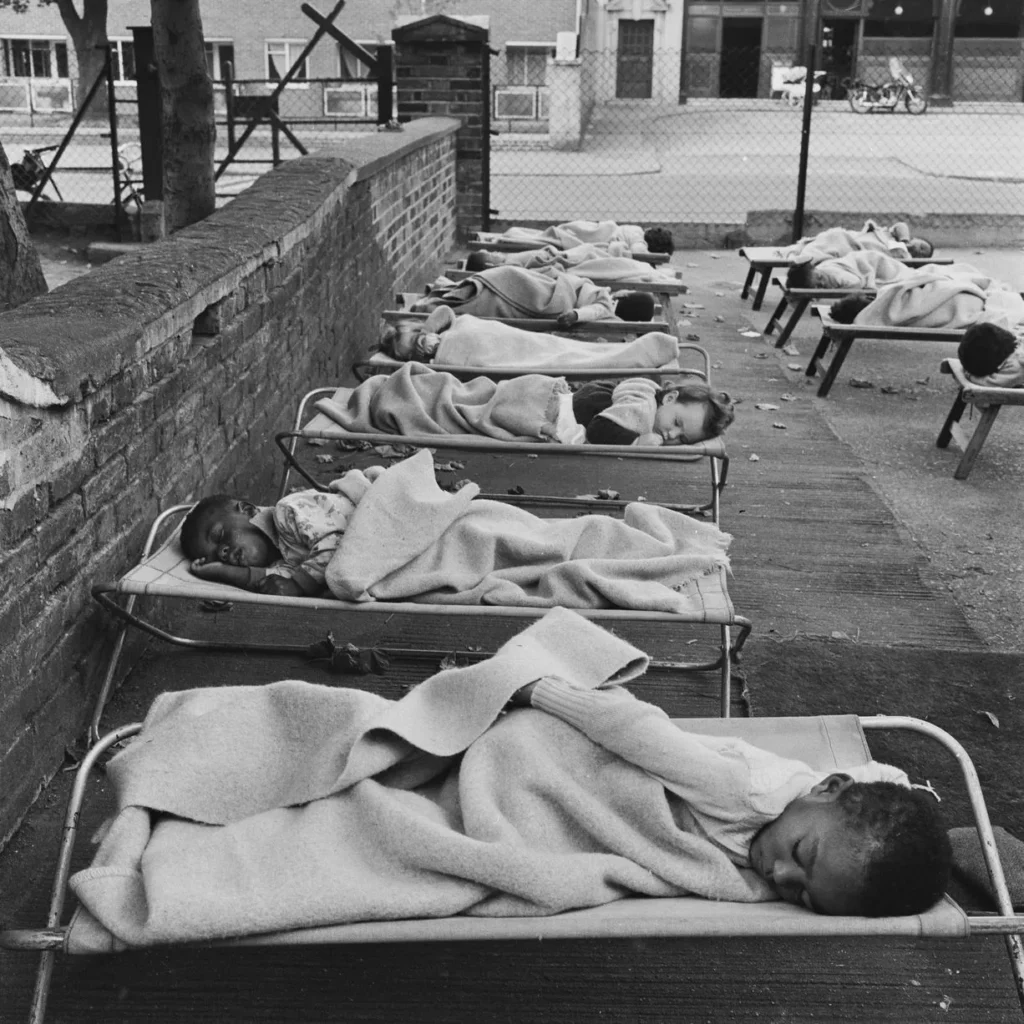

The rapidly increasing immigration from the Carribeans blended into a grim mosaic of impoverished Irish, Eastern European Jews, Cypriots, Maltese, and Africans living in Rachman’s properties. Rooms were also rented to local prostitutes, burglars, murderers, and pimps. New tenants arrived in ever larger waves, pushing the exploitation of space to absurd extremes.

Microscopic rooms were now subdivided into sections separated by cardboard partitions, where people slept in shifts, much like in the Victorian night shelters of the Avernus. Tenants who fell behind on rent were reminded of their debts by dead rats thrown onto their beds or by having their underwear dusted with itching powder. It was also common practice to dump rotting rubbish inside a defiant tenant’s room or to throw their belongings directly onto the street. Rachman’s employees, responsible for rent collection in the area, were often professional boxers and wrestlers who patrolled the streets accompanied by German Shepherd dogs.

The End of an Era

The slum landlord first came to the attention of the authorities in 1959, when he began cruising London’s streets in a Rolls-Royce with a hired chauffeur – a conspicuous display of wealth that contrasted sharply with the squalor of his properties. A special police unit uncovered a web of more than thirty-three companies controlling his empire and revealed his involvement in renting rooms to prostitutes by the hour.

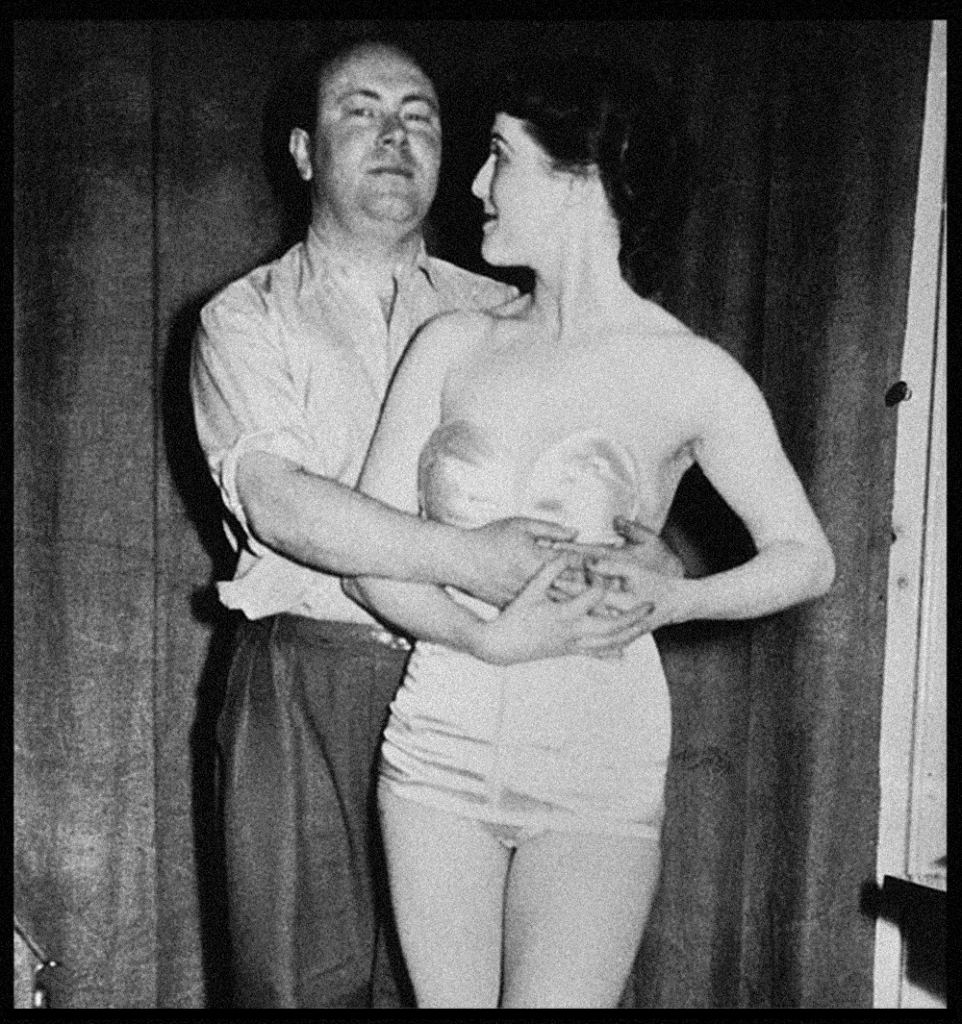

By the end of the 1950s, Rachman had begun to withdraw from his earlier illegal ventures and invest in property development, likely sensing growing police scrutiny. In March 1960, he married his long-time girlfriend, Audrey O’Donnell, though his personal life remained steeped in scandal, shaped by close associations with figures from London’s criminal underworld. Following a series of heart attacks, Perec died in November 1962 at Edgware General Hospital, aged forty-three, and was buried at Bushey Jewish Cemetery. At the time of his death, he was not only a millionaire but also stateless: his birthplace, the Polish city of Lviv, had fallen under Soviet control, and Britain had refused him citizenship.

It was only after his death, when the full scale of his ruthless practices emerged, that Rachmanism entered public consciousness and political debate, prompting calls for reform. In response, new housing legislation – notably the Rent Act 1965 – was introduced to curb exploitative landlord practices and strengthen tenants’ rights.

A Slow Rehabilitation

The inhumane housing conditions prevalent in the eastern parts of Notting Hill began to improve in the mid-1960s. Most of Rachman’s former slums were demolished and replaced with council housing, while buildings suitable for renovation underwent extensive refurbishment during the same decade. Today, these areas are home to communities originating from Portugal, Spain, and Morocco.

A significant rehabilitation of Notting Hill’s reputation, however, occurred only in the 1980s, when a new wave of affluent middle-class residents returned to the former aristocratic houses and restored their long-forgotten splendour. The area around Portobello Road once again became fashionable – inhabited mainly by wealthy, avant-garde Londoners, often well-known artists.

Discover more from London Macabre

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.