John Hunter is not a man who lends himself comfortably to summary. To attempt to write the entire life story and long list of his accomplishments in a single article would be impossible – not to mention dismissive of the breadth of his relentless quest to uncover the workings of the human body, and the lengths to which he was willing to go, often illegally, in order to obtain human remains for dissection.

Let me, then, be realistic and focus instead on the many marvellous exhibits that can still be visited today at the Hunterian Museum. As we walk past glass jars containing human foetuses, dissected rectal cancers, and syphilitic skulls, I will attempt to highlight some of the most extraordinary episodes in Hunter’s life.

More importantly still, I will try to dissect his persona and decide whether he was merely a genius ahead of his time, a naturally gifted surgeon, or – more unsettlingly – a deeply disturbed man who found a legal and celebrated means to experiment upon, torment, and wade elbow-deep in blood through thousands of different creatures, including more than two thousand human cadavers.

Trophy-Taking by Another Name

The Hunterian Museum today remains one of the most shocking, yet awe-inspiring, museums in London. It houses what survives of the pathological collection of John Hunter, which originally comprised nearly fourteen thousand individual items. These included more than 1,400 animal and human specimens preserved in spirits; 1,200 dried bones, skulls, and skeletons; 6,000 pathological preparations demonstrating injury and a wide range of diseases; 800 dried plants; as well as stuffed animals, corals, and shells. In total, over 500 species were represented, not to mention approximately 3,000 fossils, amassed throughout Hunter’s surgical career from 1748 until his death in 1793.

Unfortunately, some of his prized exhibits did not survive the passage of time, bacteria, and war. In May 1941, during a bombing raid in the Second World War, the building of the Royal College of Surgeons was struck, destroying roughly two-thirds of the museum’s total collection. Thankfully, we are still in possession of approximately 3,000 to 3,500 specimens from John Hunter’s original hoard. Around 2,000 of these, displayed in elegant glass cases, can still be viewed free of charge.

A Curious or a Disturbed Mind

John embarked upon his path to becoming one of London’s most famous surgeons through truancy and the habitual skipping of classes. Struggling to read and write, he despised school and the study of the classics, dismissing their backwards-looking thinking, rooted hundreds of years in the past. By the age of thirteen, his parents had effectively abandoned his formal education altogether. John was left to roam the rural Scottish countryside, free to explore nature and to ponder questions for which no adults seemed able – or willing – to provide answers.

He witnessed births and deaths among horses, cattle, and fowl; observed neighbours attempting to act as veterinary surgeons; and studied the behaviour of wildlife. It is highly probable that Hunter undertook his first attempts at animal dissection there and then – a practice he would later openly acknowledge, remarking on the benefits of dissecting in open fields. Whether these were decaying wildlife corpses he found already expired, or animals he procured himself, remains a mystery.

Modern psychiatrists, hearing of a young boy so intensely fascinated by both living and dead creatures that he began examining their internal structures, would likely consider pathological behaviours associated with psychopathy or sociopathy. Yet in the eighteenth century, John was regarded simply as a naturally gifted child who learned from observation rather than books – and whose early passion for biology would, in time, evolve into a genuine obsession.

Collecting the Dead

In 1748, John joined his elder brother William – by then already an established surgeon and male midwife in his own right – to assist in running the Anatomy School in Covent Garden. He moved from rural Scotland to the very heart of London, where his ambitious, impeccably presented brother, white gloves and all, introduced John to the practical realities of anatomical study: the business of obtaining human cadavers for students. By any means necessary.

Uneducated and uncultured, John was a gamble for William’s reputation and his wealthy acquaintances in high places. Yet before long, the younger Hunter proved himself an indispensable assistant, furthering the success of William’s school for eager surgical students seeking practical instruction in dissection. The school’s prosperity depended largely on a promise made to every pupil: access to a fresh cadaver on which to practise. John was responsible for securing enough bodies to prepare specimens for demonstration – preserved in glass jars – as well as intact corpses upon which students could conduct their own dissections.

This was no easy task. Despite the frequency of executions in London, with criminals regularly hanged at the Tyburn Tree, the supply was insufficient. To ensure a steady and reliable stream of the dead, the twenty-year-old John was forced to cultivate close relationships with the capital’s underbelly. With rampant poverty, disease, and the anonymous sprawl of the metropolis, London seemed an ideal hunting ground.

Resurrection Men at Work

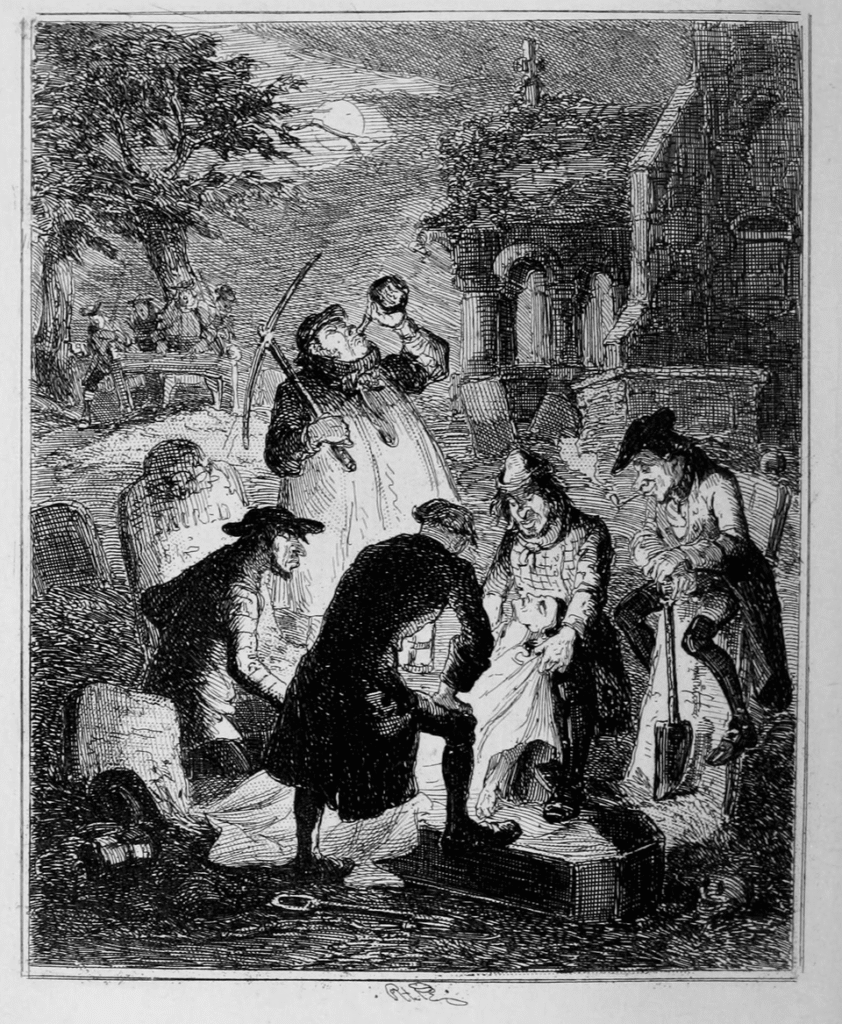

A dead body, even in the coldest London winter, could last little more than a week before decomposing. Hunter therefore faced the challenge of maintaining a constant flow of barely deceased people – shoved into large sacks and delivered to the back door of the Covent Garden school in the early hours of the morning, almost every day.

The shrewd young man began frequenting the seedy taverns of central London. His rough manners, plain clothing, fondness for drink, and unashamed cursing allowed him to mix easily with petty criminals, the unemployed, and vagrants. From them, he learnt where the dead might be found. The gallows were one source, though surgeons often had to battle grieving families for the criminal’s corpse. Visiting the condemned before execution to purchase their bodies in advance – sometimes in exchange for money to buy decent clothes for their final day alive – was another method. Certain undertakers could be bribed to surrender a corpse, replacing it in the coffin with stones before burial.

Even these measures, however, were not enough. John was eager – even anxious – to excel at the only occupation he had ever found himself interested in. He knew that the only truly inexhaustible supply lay in one place: the grave.

A Free Market in Corpses

When he arrived in London in 1748, grave-robbing – later known as body-snatching – was still in its infancy. Such thefts did occur, but they were neither widespread nor systematic. John changed that.

He transformed it into a fully organised industry, employing gangs of so-called resurrection men who fanned out across the capital night after night, searching for fresh graves and delivering corpses to the back of William’s house. This profitable but grim trade endured until 1832, when the Anatomy Act finally provided medical men with a legal means of acquiring bodies for dissection. In John’s time, however, it was a free-for-all.

There was no law assigning value to a dead body, and so technically, taking one was not a crime – unless you were caught. The deceased possessed no legal rights over their remains, and John Hunter operated with a free hand, supported by a formidable network of ringleaders firmly on his brother’s payroll. It is enough to say that in the twelve winters he spent at Covent Garden with William, John admitted to being present at more than two thousand dissections of human bodies.

The Means of Discovery

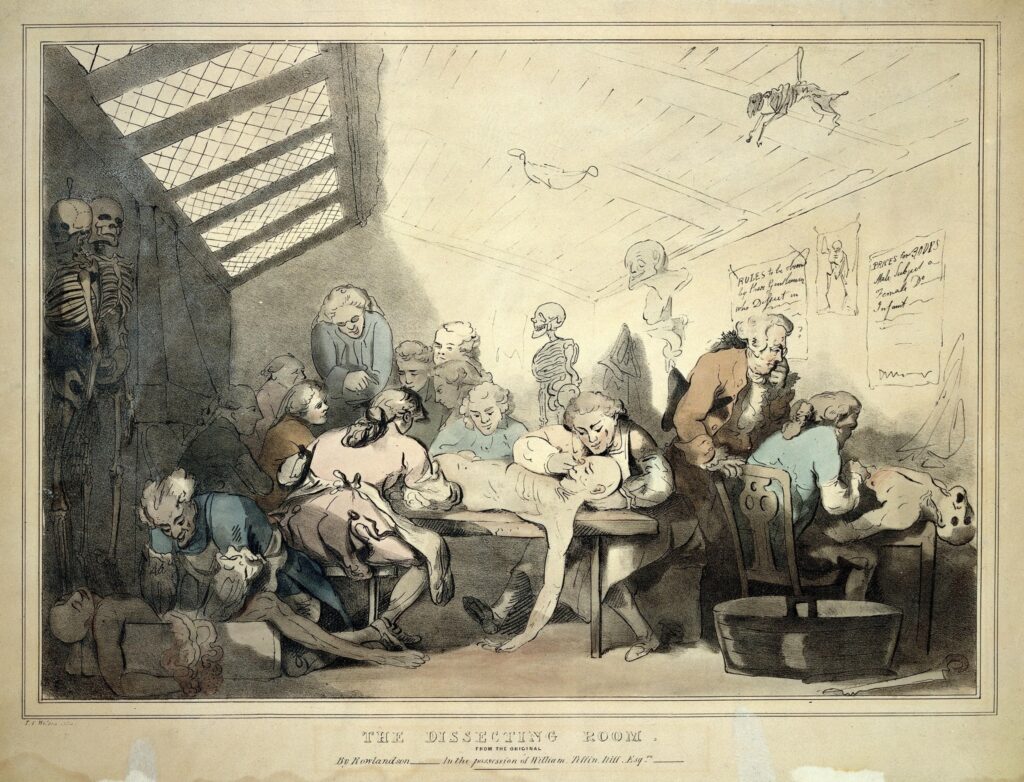

Under his brother’s supervision, John soon became more skilled than the master himself, and eventually almost all work in the dissecting room was handed over to him. His fingers were impossibly precise, his dissections so delicate that they could expose a single nerve threading its way through a dense mass of tissue. He spent countless hours pickling organs in spirits; drying bones and muscles before varnishing them; and injecting intricate networks of veins with dyes or coloured wax.

Cutting, sawing, probing, picking, and pricking raw human flesh, John bent for hours over his dissecting table in a small room steeped in the rancid stench of rotting bodies – a smell that clung stubbornly to his coat, hair, and blood-stained hands long before the advent of medical gloves. It followed him beyond the school walls, a fetor shared by the teacher and the pupils who gathered around him, fascinated by his work.

Had that not been disturbing enough, Hunter’s pursuit of discovery extended beyond smell, sight, and touch. Students were encouraged by their teacher to taste various bodily fluids and draw their own conclusions, in the absence of other forms of scientific analysis. John himself recorded in his notes, with striking matter-of-factness, the taste of urine, gastric juice, urethral mucus, semen, and blood.

The Quest for Pregnant Cadavers

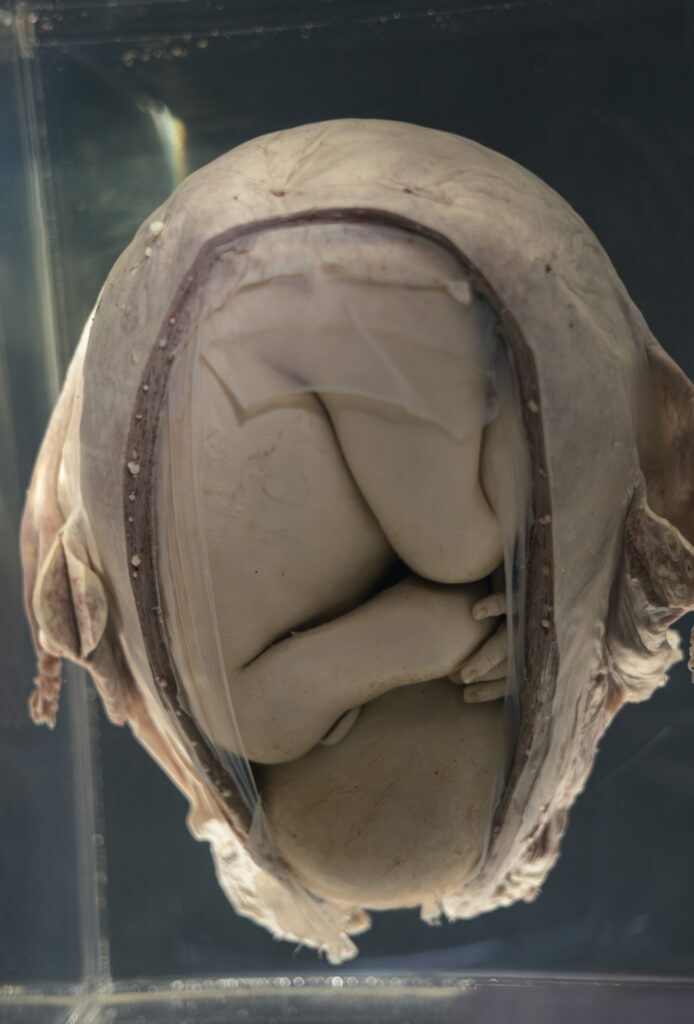

Pregnant women remained among the most frequent and highly prized requests made by William. Such bodies were exceptionally difficult to obtain, and the anatomy of the pregnant womb remained largely obscure. William was keen to conduct original research, to gain professional distinction through discovery, and to broaden his expertise as a surgeon and male midwife serving the daughters and wives of London’s aristocracy.

John supplied exactly what his brother demanded. Through his underground network, he secured the bodies of several women at different stages of pregnancy, their heavy forms dragged from coffins and delivered to John’s back door on the very night of their exhumation.

Then, in the winter of 1750, William’s lifelong ambition was realised. A body-snatcher delivered the corpse of a woman in her ninth month of pregnancy. She had died suddenly just days before giving birth; the unborn child remained intact within the womb. It was a chance occurrence of almost unimaginable rarity. Bodies in such a condition were virtually unheard of: pregnant women were spared the death penalty, and fatal complications occurring mere days before childbirth were uncommon. Despite having trained with the finest male midwives in London, William had never seen a fully developed foetus within the womb.

Anatomy of a Break

All dissection was entrusted to the skilful hands of the cold-blooded John. Before work on the first body was even completed, two further pregnant cadavers arrived in quick succession, providing additional material for experiment. News of John’s latest and most specific request must have travelled across London faster than the wind.

As a result of John’s relentless work, he soon established that mother and foetus possessed separate blood supplies, despite their intimate proximity within the placenta, where nutrients and oxygen were exchanged. This was a major discovery, for which William took full credit. The injustice later caused a deep rift between the brothers, whose relationship was never fully repaired.

Success in the Shadow of Contempt

After twelve years at his brother’s side, having become a master of dissection and arguably the most informed man on human anatomy in Europe, John finally parted ways with the overbearing and controlling William. He undertook a stint in the army as a military medic, which allowed him to practise as a physician without completing formal theoretical schooling. On his return to London, he worked briefly alongside a dentist before securing a post as a young surgeon at St George’s Hospital. By this point, John had achieved a measure of professional recognition: a widely known anatomist, a practitioner at St George’s, and the owner of a modest but steadily growing private practice.

None of this came without jealousy, rivalry, ridicule, hostile press, and the disapproving scrutiny of fellow physicians. Famed for his risky – yet at times miraculous – surgical interventions, he was increasingly sought after, and his name began to circulate widely, though not always favourably. In some circles, including his brother’s, it was spoken with restraint rather than admiration.

The Risks He Took

Hunter refused to defer to ancient Greek doctrines, the unproven virtues of bloodletting, leeches, or – above all – amputation as the default surgical solution taught in medical schools of the time. He had spent enough time immersed in human flesh to understand that careful observation, experimentation, and trust in the body’s natural capacity to heal were the only paths forward. In this way, he developed an early and remarkably modern conception of scientific analysis in medicine.

For instance, on the battlefield gunshot wounds were treated uniformly – and disastrously. Surgeons enlarged wounds, insisted on extracting bullets at all costs, often with unwashed hands and no understanding of antiseptics, frequently ending in infection and death. John adopted a radically different approach. He left bullets in place, removing only fragments of shrapnel that posed a clear risk of inflammation. Most soldiers recovered. His fellow doctors, however, regarded these methods as reckless and absurd.

Likewise, rather than resorting to amputation as the sole treatment for popliteal aneurysms, Hunter developed a groundbreaking procedure in which he cut off the blood supply to the affected vessel and allowed the body to redirect circulation naturally over time. The operation proved remarkably successful and earned him recognition across the Channel. His colleagues at St George’s, however, remained unimpressed, dismissing his work as dangerous experimentation and little more than educated guesswork by an unschooled butcher.

Beyond Ethical Restraint

During his partnership with James Spence – one of the most prominent dentists in London – John had become obsessed with the idea that all living tissue could grow, mend, and perhaps even fuse together. This belief led him into a series of strange and ethically dubious experiments, first on live animals and later on human beings.

Among his most bizarre grafting experiments was the removal of a spur from a cockerel’s foot and its transplantation into the bird’s comb, where it appeared to take hold and continued to grow. Next came a rooster from which one testicle was removed and implanted into its own abdomen; the graft was accepted and continued to function as living tissue.

Intrigued by this apparent success, Hunter proceeded to implant another testicle – this time into the belly of a hen. Once again, the graft was not rejected, likely owing to the close genetic similarity produced by inbreeding. One pupil also reported an experiment involving the transplantation of a cow’s horn onto a donkey’s head, though whether this succeeded remains unrecorded.

From Experiment to Exploitation

Encouraged by his results and increasingly exhilarated by the implications, Hunter found a poor man in need of money and, in exchange for a fee, removed one of his healthy teeth. He then implanted it into the comb of a cockerel. The hybrid later became one of his most prized specimens, as the two living tissues appeared to accept one another. If the sight of a cockerel bearing a human tooth in its head seems bizarre, it is worth remembering that Hunter rarely stopped at a single experiment.

He soon shared news of his apparent success with his dental partner. Before long, Hunter began purchasing healthy teeth from the poor and destitute for modest sums and implanting them into the mouths of the wealthy for enormous fees. The practice expanded rapidly, driven by clients desperate to rid themselves of decaying teeth. Tooth transplantation was not new – it had been practised in Paris and northern England before Hunter’s return from the army – but it had largely fallen out of favour due to moral concerns. Hunter, however, was untroubled by such objections and single-handedly revived the practice in London, at least for a time.

The Venereal Experiment

There was another path to discovery in John Hunter’s mind – one that might not have occurred to any other surgeon. To contract a disease deliberately, observe its progression, and experiment upon oneself in search of a cure. Yes, he almost certainly did this. What is more, the illness he chose was venereal disease, which at the time was incurable.

On a seemingly unremarkable Friday morning in 1767, as recorded in his notes, Hunter dabbed his surgical knife into a gonorrhoeal sore and then stabbed twice into a healthy man’s penis – once at the tip and once beneath the foreskin. He did not record the name of his volunteer, but given the minute detail with which he later described the progression of the disease over more than three years, it is highly probable that he himself was the subject of this experiment.

Gonorrhoea and syphilis were both widespread in Georgian London, affecting all classes of society, from common prostitutes to its most elevated members. Hunter, like the majority of physicians of his time, believed the two diseases to be one and the same. Gonorrhoea was thought to be a local venereal infection confined to the genitals, while syphilis was believed to represent its more advanced, systemic stage.Hunter’s experiment was intended to prove this theory once and for all – that both conditions were manifestations of a single disease.

Over the course of three years, the anonymous patient first developed the expected symptoms of gonorrhoea, which were later replaced by ulcers and sores on the genitals and tonsils typical of syphilis. Hunter was elated: in his mind, the hypothesis had been conclusively proved.

Error, Consequence, and Denial

The brutal truth, however, is that such an outcome was almost inevitable. As both diseases were transmitted in the same manner, many patients suffering from gonorrhoea were also infected with syphilis. It is now understood that Hunter must have taken pus from a patient harbouring both diseases simultaneously.

After three years of suffering – and following the successful publication of his thesis detailing the experiment – all visible symptoms disappeared. Syphilis had entered its latent, non-contagious phase, but unknown to John, it remained within his body until his death. Within a few years of the experiment, his health began to deteriorate gradually, displaying symptoms now recognised as possible early signs of tertiary syphilis.

Whether conscious of his hidden illness or not, John decided that it was high time to marry his long-time sweetheart, Anne Home, fourteen years his junior. The couple married in the summer of 1771. The potential risks of the union for his wife, as ever, appeared to concern him far less than the experiment itself. His first son followed a year later.

The Vivisectionist of Earl’s Court

Having purchased farmland away from London in the tranquil village of Earl’s Court, John created a quintessential country retreat for an anatomist eager to experiment on farm and exotic animals without the inconvenience of prudish neighbours. Although his villa was well screened by gardens and numerous outbuildings, it was not long before any passer-by peering through the iron gates found it difficult not to stare.

The lawns were grazed by an improbable assortment of sheep, horses, Turkish rams, zebras, cattle, and mountain goats. He was also known for the dangerous menagerie locked within the grounds: a lion, a jackal, a dingo, and two leopards. On occasion, he would drive from the quiet village into the crowded streets of west London with three Asian buffalo harnessed to his cart in place of horses.

Beneath the house lay an underground laboratory containing a large copper vat, in which Hunter boiled down the bodies of deceased animals – and sometimes humans – to obtain their skeletons. He froze countless fish and rabbits in the hope that, if revived once thawed, they might one day reveal a path towards human immortality.

The Knife Without Mercy

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Hunter did not flinch from vivisection. On the contrary, he conducted numerous experiments on live dogs, chickens, and pigs, tied to his dissecting bench while he cut them open and examined their internal organs until the tortured animals finally expired. No animal was too small – or too large – for John’s knife.

He was also an avid collector of animal and human peculiarities. His hoard included the brain of a two-headed calf, a kitten with two mouths, and a pig with two bodies, displayed alongside the remains of a human child born without a skull. Neighbours might glimpse a three-legged goat prancing across the gardens, or strange cross-bred – often sickly or deformed – animals produced by Hunter himself, including a hybrid of zebra and common donkey.

Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

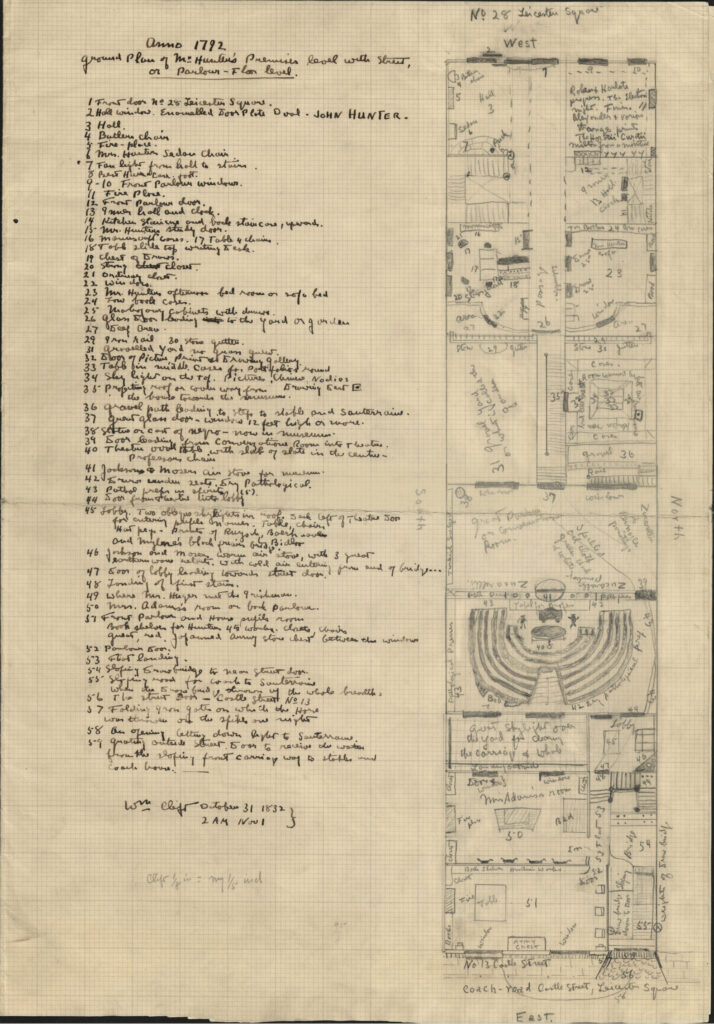

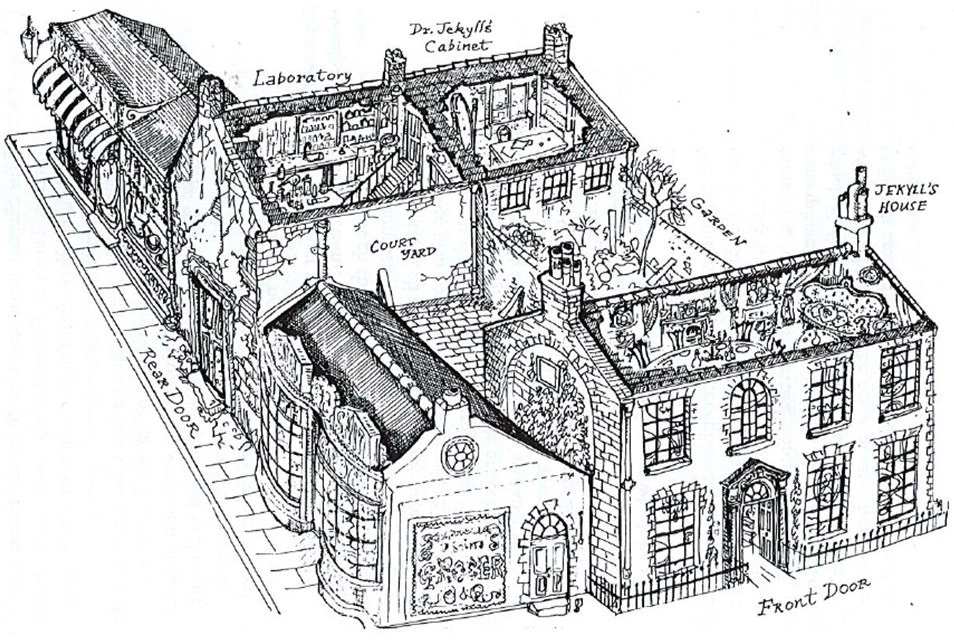

Meanwhile, his final townhouse on Leicester Square was anything but dull. The obsession of hoarding reached its culmination with this last move, from Jermyn Street to a purposefully remodelled residence overlooking the square. Hunter was adamant that his vast collection should one day form a museum capable of sustaining his wife and children after his death. Crucially, he refused to separate the museum, laboratory, dissecting rooms, and in-house anatomy pupils from the family home.

To achieve this, Hunter purchased two houses. The first was a respectable townhouse on Leicester Square itself, with a handsome façade suitable for his well-to-do family. The second stood on Castle Street, a narrow alley behind the square – smaller, shabbier, and far more cramped. The two properties shared adjoining gardens. Hunter constructed a door from the family house leading into an extension that ran the entire length to the Castle Street property, forming a long internal corridor.

Along this passage, arranged over two levels, he installed his museum, lecture theatre, dissecting rooms, and laboratory. The Castle Street house itself lodged his anatomy pupils. A ramp was attached to the rear of the building, discreetly opened at night to receive fresh deliveries of cadavers. Meanwhile, aristocratic patients of Dr Hunter approached the black-polished front door on Leicester Square, entirely unaware of what transpired behind the house. This divided residence and dual existence later served as direct inspiration for The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, with Dr Jekyll himself modelled in part on John Hunter.

The Moral Weight of a Visionary

Hunter’s collecting obsession was an expensive habit. Some specimens were gifts from friends and benefactors, but the vast majority were purchased from circus owners, auctioneers, private collectors, travellers, and fair proprietors exhibiting human curiosities.

The cost of acquiring fresh bodies mounted steadily. With an expanding family and a wife who enjoyed a certain standing in London society, debts accumulated unavoidably. Glass jars and preserving spirits were costly, as was the growing staff at Earl’s Court required to manage his extensive animal flock. Even as an eminent surgeon holding three paid posts, with a wealthy clientele and numerous publications to his name, Hunter was slowly drowning financially – and dragging his unknowing family down with him.

Having suffered from painful angina for years, and expecting his life to draw to a close, he grew desperate to ensure his museum would be as large and as famous as possible, in the vain hope that it might secure his family’s future. What he failed to consider were the times themselves. England was at war, and the government declined to purchase his collection upon his death from a heart attack in 1793.

Between Memory and Ruin

His Earl’s Court retreat remained under mortgage, as did his new home at 28 Leicester Square, which had cost an astonishing £30,000 (the equivalent purchasing power of roughly £5.8 million today) to build and remodel. Creditors descended upon the family with news of the doctor’s death. Once all debts were settled, little remained. Anne was left with only a modest income. Both properties were sold, and she retreated to John’s childhood farm in Scotland, soon forgotten by society. Eventually, the museum was purchased by the government for a fraction of its value and transferred to the Royal College of Surgeons. Both the Earl’s Court retreat and 28 Leicester Square were later lost to demolition and redevelopment.

There is no doubt that John Hunter remains one of the most famous names in English medicine, a man who helped forge the foundations of modern scientific practice. Yet a final question lingers. Where, precisely, does the scientific curiosity of a brilliant mind end – and the obsessive possessiveness of a serial collector begin? And with all that has been touched upon here, can one ever be certain where Dr Jekyll ends, and Mr Hyde begins?

Discover more from London Macabre

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.