In 1888, a series of brutal murders unfolded in the deprived district of Whitechapel, resonating far beyond London. Details of the horrific attacks, attributed to a single, ruthless assailant nicknamed Jack the Ripper, made headlines across Europe. The case, involving at least five murders of local prostitutes, remains one of the most chilling and unsolved mysteries in English crime. But why did the killer choose to operate solely in this part of the city?

Housing Situation in the East End

Jack the Ripper remained elusive largely due to the appalling housing conditions in East London, which offered him both anonymity and a quick escape through its maze of winding, dimly lit alleyways.

By the mid-19th century, Whitechapel had become notorious as the worst neighbourhood in the Victorian capital of the British Empire. Overcrowding, lack of clean water, inhumane factory conditions, and rampant unemployment created fertile ground for the growth of vast slums. Robbery, violence, and alcoholism were rife, and endemic poverty forced many women into prostitution.

Economic hardship was compounded by growing social tensions, driven by waves of immigration to East London – particularly from impoverished Irish workers and Jewish refugees fleeing repression in Europe. Anti-Semitism, racism, and nativism, coupled with a perception of moral decay, made Whitechapel seem, in the public eye, an incurable breeding ground for crime. By 1888, fear and loathing of the slum dwellers had reached their peak.

Police Attitudes Towards Prostitutes

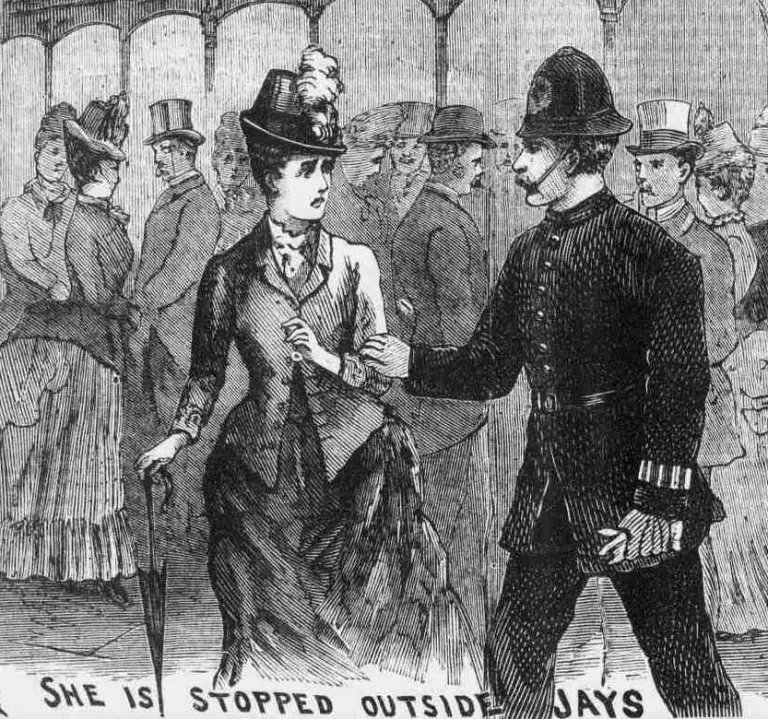

Another factor was the ease with which the killer could find potential victims – a consequence of the laws of the time and the false morality of the Victorian era. Prostitution was legal in England, and the only offence punishable by arrest was openly harassing men in the street.

In 1887, newspapers reported a sensational case involving a respectable mill worker named Elizabeth Cass, who was stopped by a constable on Regent Street and charged with soliciting. Miss Cass defended her reputation in court, claiming she had merely been shopping that evening. The scandal dominated the press, leading Members of Parliament to criticise both the police and the then Secretary of State. A new regulation soon followed, forbidding officers from interrogating women unless a passer-by had lodged a formal complaint.

The immediate result was a sharp drop in arrests of streetwalkers between 1887 and 1889. Fearing dismissal, constables avoided confrontation altogether. London’s street girls thus became unpunished and emboldened – but also invisible. By the time Jack the Ripper began murdering Whitechapel’s prostitutes, the police had long since learned to overlook their presence.

Closure of Whitechapel Brothels

In 1887–88, Frederick Charrington, a wealthy East London brewer and fervent moral reformer, launched a relentless campaign to expose and close local brothels. His crusade shut down more than 200 establishments in Whitechapel. While intended to improve the district, it had disastrous consequences for the women who lived and worked there – and inadvertently aided Jack the Ripper’s crimes.

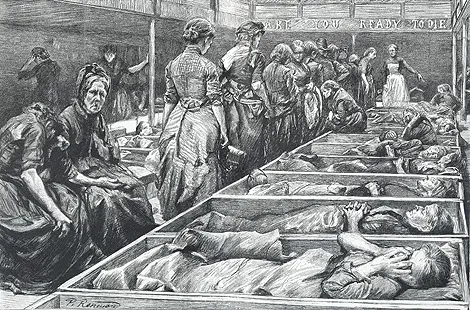

Deprived of protection from brothel owners – often older prostitutes known as madames – and of the companionship of other women, the street girls became more vulnerable to violence. Services once offered in the relative safety of small rooms were now conducted in dark, filthy alleyways off Whitechapel Road.

Unable to stay overnight in a madame’s quarters, women had to earn enough each day to afford a single bed in one of the nearby lodging houses. Those who failed to do so slept under viaducts, in doorways, or simply out in the street, seeking warmth and forgetfulness in cheap gin. By the autumn of 1888, hundreds of homeless, often alcoholic prostitutes wandered the East End’s streets.

Finding the murderer was further complicated by the diversity of clients who frequented Whitechapel. The nearby docks brought a steady flow of sailors looking to spend their wages. The market on Whitechapel Road attracted merchants and farmers. Middle-class men ventured east for cheap and readily available sex – something that would cost them far more in the West End. Even aristocrats came, not for economy but for the thrill of anonymity and the freedom to indulge their darker whims.

Crime Rates in the District

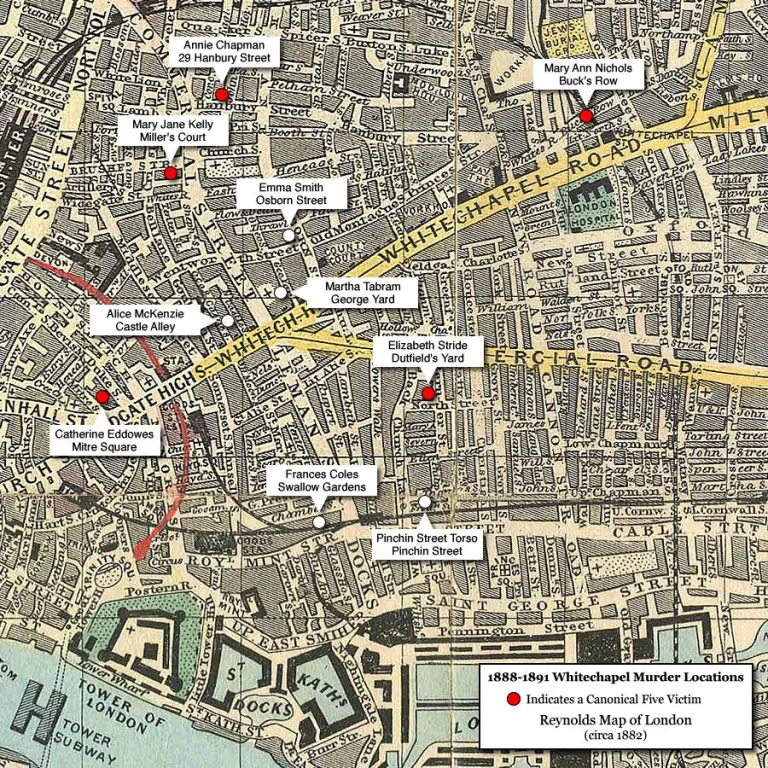

A review of Victorian newspapers shows that assaults on women were almost daily occurrences in East London. Between 3 April 1888 and 13 February 1891, eleven murders were committed in or near the district. Five of these victims were definitively attributed to Jack the Ripper: Mary Ann Nichols (d. 31 August), Annie Chapman (d. 8 September), Elizabeth Stride (d. 30 September), Catherine Eddowes (d. 30 September), and Mary Jane Kelly (d. 9 November).

The remaining six murders, which either preceded or coincided with the Ripper’s activities, bore similarities in method and violence but were ultimately excluded from the canonical five. However, during the investigation, police treated all eleven cases as potentially connected and grouped them under a single file known as the Whitechapel Murders.

This file was first opened after the death of Emma Smith, who was robbed and assaulted on Osborn Street on 3 April 1888. She died the next day from peritonitis but managed to describe her attackers – three men believed to be members of a local gang.

To this day, debate continues as to whether Jack the Ripper was responsible for only the five recognised murders or for some of the others recorded in the Whitechapel Murders file. More than a century later, the mystery endures, and the narrow streets of Whitechapel still seem to echo with the footsteps of both the hunter and the hunted.

Discover more from London Macabre

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.