Kitty Fisher was born in 1741 as Catherine Maria, the impoverished daughter of a corset maker. She caught the eye of Admiral Augustus Keppel, who introduced her to London society. (Other sources suggest General Anthony Martin may have been her first patron.) She began her life in the capital as a humble maid, but the glamorous life of high-class prostitute proved far too tempting. Once she stepped into the salons, the young teenager swiftly acquired notoriety through numerous affairs with titled and wealthy men.

Within just a few years, Kitty Fisher had forged her own legend, using her striking beauty and carefully commissioned portraits by London artists to captivate the public imagination. Her charm and audacity were amplified by paintings and press coverage, drawing both admiration and envy. Her fashions and hairstyles were studied, copied, and obsessively imitated by young women eager to emulate her. Miss Fisher was among the first true celebrities, meticulously crafted and promoted by early English mass media, whose fame rested solely on the scandalous extravagance of her lifestyle.

Ascending the Salons

Kitty’s first official appearance as a courtesan is chronicled in the playful memoirs of Augustus Keppel, published four years after her untimely death. According to his account, the admiral encountered the radiant 18-year-old in London and immediately decided to become her protector. Though he lavished her with gifts and a life of luxury, Kitty swiftly turned from him, embracing her role as one of the capital’s most sought-after, high-class courtesans. She established her residence on Carrington Street, near Shepherd Market in Mayfair, an area long famed for hosting London’s elite prostitutes.

The Art of Self-Promotion

Fame, of course, demanded more than beauty alone. Women like Kitty relied on subtle marketing to secure their place in society’s gaze. Flyers and pamphlets praising the charms and services of courtesans often circulated among gentlemen. Kitty’s promotional material boasted that, alongside ‘complete satisfaction, the fee included witty and intelligent conversation.’

Once she had amassed sufficient wealth, she engaged one of England’s most celebrated painters, Joshua Reynolds, to paint her portrait. The artwork became an instant sensation. Copies were swiftly reproduced and widely distributed by London publishers in miniature form. At the peak of her career, posters of Kitty appeared in the windows of countless print shops, alongside pamphlets detailing her most recent romantic exploits. The likenesses of the city’s most illustrious courtesans sold like hotcakes, effectively establishing them as the first erotic models. Some miniatures were deliberately tiny, intended to be concealed in a gentleman’s pocket watch or snuffbox.

Kitty became Reynolds’ favourite muse, appearing in several of his works, including a famous depiction as Cleopatra dissolving a pearl in wine – a striking reflection of her insatiable appetite for wealth and indulgence. Nathaniel Hone also immortalised her in 1765; this portrait still resides in the National Portrait Gallery.

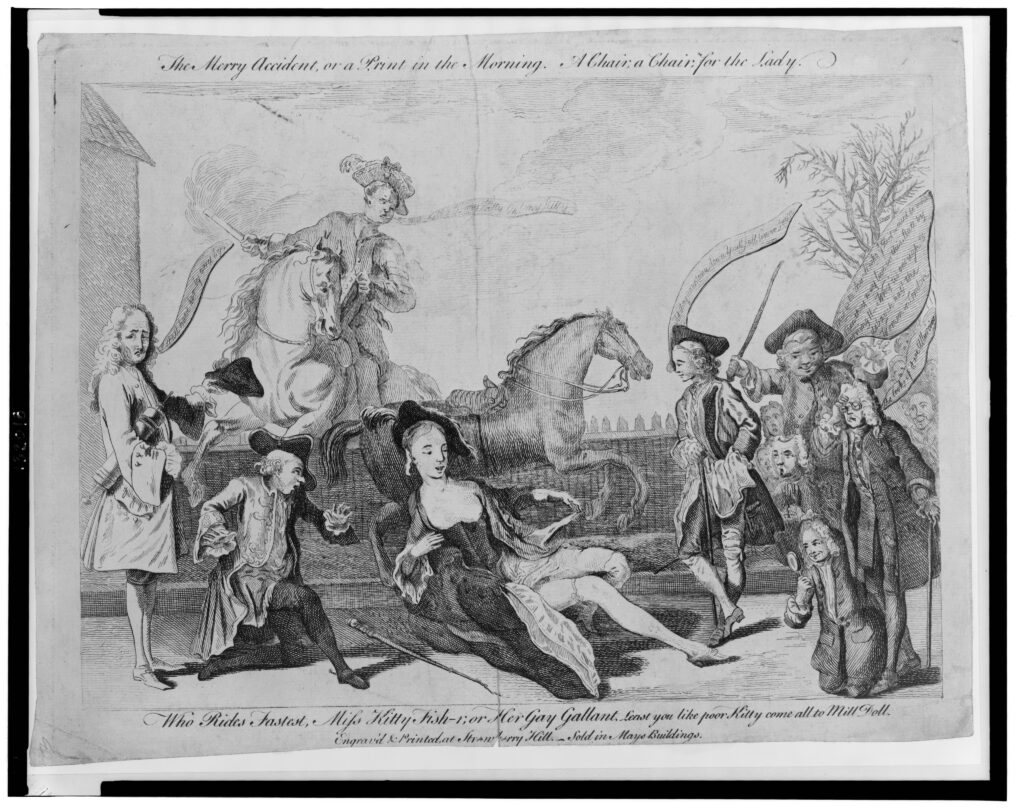

A Scandal in St James’s Park

Kitty sought attention in more public arenas as well. On one occasion, she made headlines at St James’s Park. During a horseback ride, her horse reared violently, throwing her to the ground. Though unharmed, her skirts and petticoats were lifted high, revealing far more than modesty allowed. Initially overcome with tears, she soon succumbed to hysterical laughter, hailed a carriage, and departed the scene.

Witnesses remained stunned at the memory of her exposed backside, while journalists enjoyed a particularly productive day. Newspapers published mocking songs, articles, and satirical pieces lampooning the unfortunate fall of a woman already considered fallen. Whether this incident was a genuine accident or a calculated publicity stunt remains unknown, but it did nothing to harm her career; indeed, it may well have enhanced her fame.

International Notoriety and Casanova

Miss Fisher’s pride in her profession and her skill in it soon earned her fame beyond England. Her renown rivalled that of the French courtesan Madame Pompadour. The famous lover Giacomo Casanova, visiting London in 1763, encountered Kitty and later described the meeting in his memoirs:

“We went to Mrs Walsh, where we met the famous Kitty Fisher. She was awaiting the arrival of Prince X, who was to take her to a ball. She wore diamonds worth at least 100,000 crowns (roughly £2.5 million today). Goudar suggested that, if I desired, I could have her for ten guineas (about £1,000 today). I declined, for although charming, Kitty spoke only English. Accustomed to loving with all senses, I could not indulge fully without the ability to communicate.”

It is unclear how trustworthy Casanova’s account is. Other sources claim the young woman spoke fluent French. Perhaps the Italian exaggerated to underline that he had willingly refused the services of a courtesan admired across Europe.

Extravagance Beyond Measure

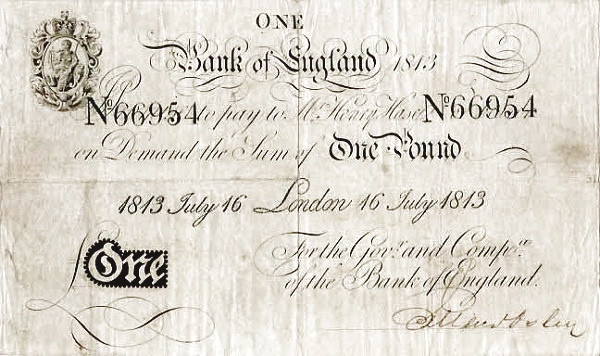

Kitty was famed not only for her beauty but also for her audacious appetite for her lovers’ wealth. Literally. On one infamous occasion, she publicly consumed a £100 banknote (equivalent to around £10,000 today). Casanova mentions the incident:

“Mrs Walsh told us that it was in her house that Kitty ate a £100 banknote on a slice of buttered bread, given to her by Sir Richard Atkins, the brother of the beautiful Mrs Pitt. In this way Fryne (as Giacomo called Miss Fisher) made a gift to the London bank.”

In 18th-century England, a banknote served as a bearer cheque, certifying the owner’s gold deposit. By swallowing it, Kitty forfeited her claim to the funds. Casanova implies this was both extravagant and provocatively defiant – especially towards one of the country’s most venerable institutions, the Bank of England. Kitty’s act was likely intended to taunt her admirer, revealing the transactional nature of their relationship. Banknotes were considered less secure than coins, and in consuming it, she publicly humiliated her lover, who in her eyes should have offered gold or jewels instead. Casanova’s comparison of her to Fryne linked her to the most famous courtesan of ancient Greece.

A Life of Decadence

Her extravagant lifestyle fuelled fascination. Kitty was the first London prostitute known to employ household staff – a remarkable achievement. Rumours of lavish and licentious feasts for wealthy gentlemen abounded, and at one such dinner, she allegedly served herself for dessert. Her friends suggested her household cost £12,000 per year (about £1.2 million today). Her obsession with diamonds was legendary. Her extravagant disregard for money, combined with an unquenchable thirst for it, became hallmarks of her notorious character.

Kitty Fisher’s Nursery Rhyme

Kitty’s legend survives in the nursery rhyme Lucy Locket, still recited by children unaware of its origins:

Lucy Locket lost her pocket

Kitty Fisher found it

Not a penny was there in it

Only ribbon ‘round it

The story behind this seemingly innocent rhyme is rather risqué. Lucy Locket was a barmaid at The Cock on Fleet Street (now Ye Olde Cock Tavern). To boost her income, she took a lover who paid for her affections – the purse symbolises him. Miss Locket spent the money and abandoned him. The desperate man sought refuge with Kitty, who took him in despite having no funds. The line about the empty purse with a ribbon refers to a practice among prostitutes, who tied pouches of earnings to their thighs, hence the metaphor of Lucy’s penniless admirer tied to Miss Fisher.

Society Rivalries

Lucy Locket was not the only woman whose suitor fell for Kitty. One of the capital’s most sensational scandals involved her affair with Lord Coventry. His wife, Maria Gunning, had married through her mother’s clever manoeuvres, elevating her social standing. Insulted pride led the young aristocrat to enter an open rivalry with Kitty. Giustina Wynne’s diary records one confrontation:

“They recently met in the park. Lady Coventry asked Kitty the name of the tailor who made her dress. Miss Fisher replied that Maria should ask her husband, as he had gifted the dress. Lady Coventry called her an impudent minx. Kitty replied she must bear the insult for now, but she too intended to marry the lord, if only to one day retort.”

Marriage and Sudden Death

After several years in the limelight, Miss Fisher sought stability. In 1766, she married politician John Norris, reputedly a degenerate and compulsive gambler. His friends and family initially disapproved, despite her permanent retirement from prostitution. Kitty (now Mrs Catherine Norris) soon proved them wrong. She restored her husband’s fortune, reconciled him with estranged family members, and the couple moved to the grand Hemsted House in Kent. The local community adored her for generosity to the poor.

Tragically, just four months after the wedding, at age 25, she died in a Bath sanatorium. Smallpox or tuberculosis is considered the likely cause, though lead poisoning from cosmetics has also been suggested – a fate shared by her rival, Lady Coventry. Kitty Fisher was buried in Benenden Cemetery, dressed in her finest ball gown, per her last wishes.

Discover more from London Macabre

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.