Brompton Cemetery is counted among the seven splendid Victorian necropolises of London, built in the nineteenth century. To this day, it stands as a testament to the enterprise and refined taste of the architects and engineers of that era. Confronted with the growing problem of burials in an ever-expanding metropolis and the overcrowding of small, neglected churchyards in the city centre, the authorities resolved to create new, spacious cemeteries on London’s outskirts – today collectively known as the Magnificent Seven.

These include Kensal Green, opened in 1833; Norwood in 1837; the famous Highgate in 1839; three cemeteries from 1840 — Abney Park, Nunhead and Brompton — and finally Tower Hamlets, completed in 1841. Each displays its own distinct architectural style, reflecting the vision of its principal designer. Among the tombs one can find Greek, Gothic and Classical influences, as well as the characteristic symbolism of the age: Egyptian pyramids, angelic sculptures, horses, Celtic crosses and Grecian urns. Together, they form the very essence of the atmospheric London cemetery.

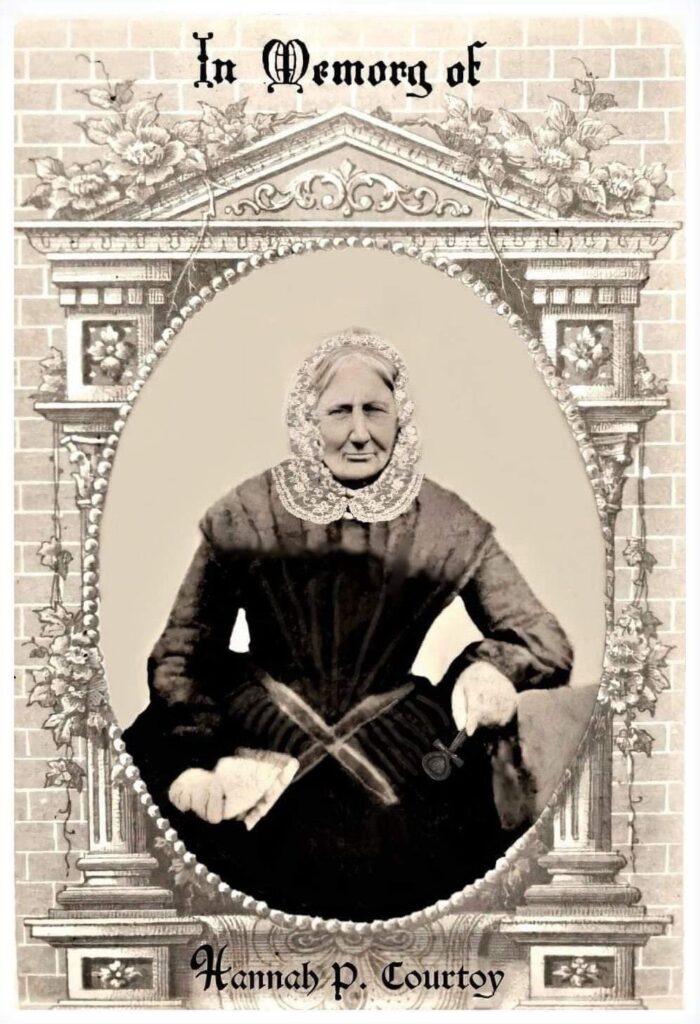

Like every self-respecting Victorian necropolis, Brompton has its share of legends and mysteries surrounding tombs that whisper tales of strange events and extraordinary lives. The most intriguing of all is the secret of Hannah Courtoy’s Egyptian Mausoleum.

The Enigma of Hannah Courtoy

In the eastern part of the cemetery, slightly apart from the main avenues, stands a remarkable tomb in the shape of a truncated Egyptian pyramid. Shrouded in mystery, it has long been associated with peculiar stories – some claiming that a working time machine is hidden within its sealed interior. Inside lie the remains of the equally enigmatic Hannah Courtoy, interred with her two daughters.

Little is known about Hannah’s life (1784–1849), but the few surviving facts and numerous speculations weave an intriguing, if incomplete, narrative. Some sources claim she worked in London as a maid; others focus on her alleged relationship with a wealthy older merchant, John Courtoy. Hannah never married, yet bore three illegitimate daughters, of whom John Courtoy is believed to have been the father. This theory gained credibility when, upon Courtoy’s death in 1815, Hannah became the heir to his vast fortune. The deceased merchant’s family tried unsuccessfully to contest the will in court. Shortly afterwards, Hannah adopted the Courtoy surname herself.

Some have speculated that she was either Courtoy’s mistress or the secret consort of a royal; others even claim she forged the will with the help of accomplices in order to seize the merchant’s assets. As a lady of London society, she left behind surprisingly few traces of her existence – an air of mystery has always surrounded her name.

The Birth of a Victorian Legend

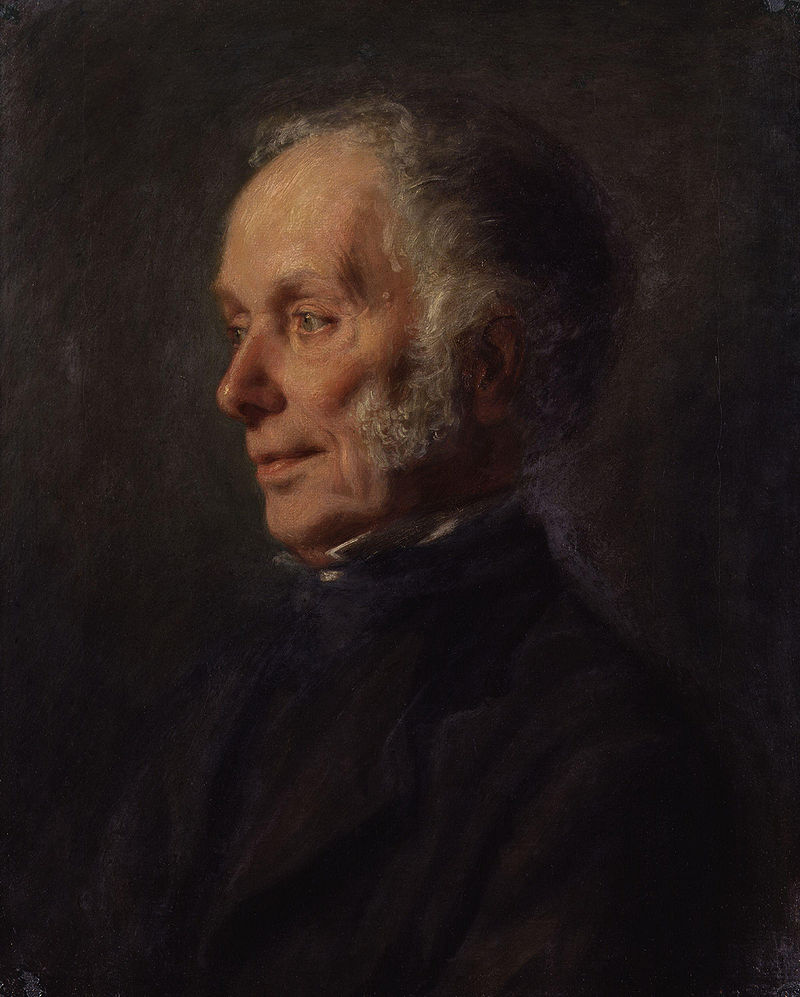

Courtoy was close with two men who may have designed her extraordinary mausoleum: Samuel Warner and Joseph Bonomi. Warner was an inventor and a conman, while Bonomi was a celebrated Egyptologist, artist, sculptor and museum curator. Hannah shared his fascination with ancient Egypt, and is believed to have financed several of his expeditions there. Known for their eccentricity, Hannah and her daughters are thought to have supported the creation of a time machine designed by the Egyptologist, who might have claimed to have uncovered the pharaohs’ lost secrets.

It is worth remembering that Victorian London was then gripped by an Egyptian mania. Symbols and motifs of ancient Egypt were immensely fashionable among the upper classes, and some believed that the pharaohs had discovered the keys to immortality and time travel. Egyptologists exploring the pyramids and tombs were rumoured to have unearthed such hidden knowledge.

Bonomi designed other Egyptian-inspired structures – notably the entrance to Abney Park Cemetery, another of the Magnificent Seven – making him the most likely designer of the Courtoy mausoleum. Other sources, however, attribute it to Samuel Warner. Curiously, both men were eventually buried near Hannah herself: Warner in an unmarked grave, and Bonomi beneath a headstone adorned with the image of Anubis, the Egyptian god of the dead, who gazes directly towards Courtoy’s tomb.

One legend claims that Bonomi and Warner were involved in occult practices and had together discovered the secret of time travel. Warner’s mysterious death in 1853 only fuelled speculation – some believe he perished as a result of his own dangerous inventions, while others whisper that Bonomi murdered him to protect the blueprints of a functioning time machine. There are even those who insist that Warner never died at all, but simply… travelled through time.

The Lost Key and the Tomb That Wouldn’t Open

The mausoleum itself inspires both unease and fascination. It stands on a small “island” encircled by a cemetery path – isolated from other graves, as though deliberately set apart. Although Hannah died in 1849, her burial did not take place until four years later, once the structure was completed. Since that time, its interior has remained sealed: the key to its heavy bronze door was lost, and no one has entered for over 150 years. Intriguingly, architectural plans survive for nearly every other structure within Brompton Cemetery – except this one.

The tomb abounds with peculiar details. At the base of its doors are carvings resembling wheels; above them, a circular window ringed by eight smaller ones. Some say it resembles the face of a clock, a mechanism – or perhaps the control panel of some strange device.

In 1998, the story once again captured the public’s imagination after a Reuters article revived the legend of the Courtoy Mausoleum. Since then, the Egyptian pyramid of Brompton Cemetery has remained one of London’s most photographed and most mysterious graves – a monument to Victorian fascination with death, science, and the elusive dream of travelling through time.

A Vision in Marble – The Architecture of Brompton Cemetery

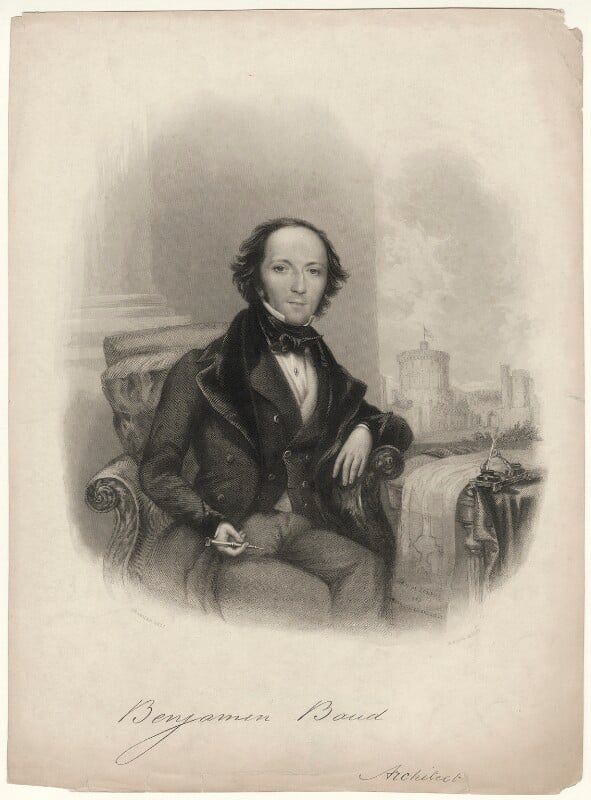

Even if time machines and the secrets of Victorian Egyptologists do not capture your imagination, Brompton Cemetery is worth a visit for its architecture alone, designed by Benjamin Baud. His vision was classical in style and strikingly ambitious.

The original plan called for high protective walls around the entire perimeter to prevent the theft of fresh corpses by the notorious resurrection men, who sold bodies to medical schools for dissection. Baud also designed two main entrances and a water gate for coffins transported by barge along the Kensington Canal, which once ran beside the western boundary. However, by the time the cemetery was consecrated and ready for its first burials, the canal had been replaced by a railway line, forcing changes to the design.

At the heart of the cemetery stand semi-circular colonnades forming an open square that leads directly to the Anglican chapel. Baud’s original concept also included two additional chapels flanking the colonnades – one Catholic, the other Nonconformist – but, like the water gate, they were never built.

Dreams, Lawsuits and Lost Fortunes

The scaling back of Baud’s grand design was due to immense financial pressures and a series of personnel changes. The architect Stephen Geary, originally employed on the project, resigned and demanded payment for his contribution, leading to a costly court case for the investors. Soon afterwards, the cemetery’s directors found themselves on the brink of insolvency. Baud’s original plans, which might have made Brompton the foremost of London’s necropolises, were drastically simplified to reduce expenses.

Tragically, Benjamin Baud himself fell victim to the company’s poor financial management and was never paid his due. Dismissed from his post, he became embroiled in a ruinous lawsuit and never recovered. Losing all heart for architecture, Baud abandoned his profession and turned to painting – a considerable loss for the fabric of London.

Despite these difficulties and setbacks, Brompton Cemetery soon became a fashionable and prestigious burial ground for many distinguished figures. The first interment took place in the year of its opening. By the 1850s, the catacombs beneath the colonnade were almost entirely filled, and by 1889 the historian Mrs Holmes described the cemetery as overcrowded, with around 155,000 burials. It is now estimated that over 200,000 souls rest there.

Silent Residents – The Famous Dead of Brompton

Brompton is dotted with graves belonging to remarkable individuals whose lives helped shape British history. Among them is Dr John Snow, the physician who discovered that cholera spread through contaminated water, halting the Soho epidemic. He was also a pioneer in the use of ether and chloroform as anaesthetics, and it was he who administered ether to Queen Victoria during two of her childbirths. Elsewhere lies Emmeline Pankhurst, the formidable leader of the suffragette movement and a tireless champion of women’s rights.

Today, Brompton Cemetery remains one of London’s most atmospheric resting places – a haunting blend of art, history and mystery. Wandering through its colonnades, tombs and trees, one can almost feel that the boundary between life and death grows perilously thin.

Discover more from London Macabre

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.