Beneath the gloomy skies of mediaeval London, the line between superstition and heresy was dangerously blurred. Here, amid the stench of the Thames and the cries of the condemned, witches were hunted, tried, and executed – their supposed crimes etched into the city’s collective memory. Yet behind every accusation lay something darker still: envy, greed, and the eternal fear of the unknown.

The First Recorded Witch of London

The first record of a witch being executed in London dates back to the 10th century. The story goes that an unnamed widow and her son were accused of driving iron pins into a neighbour’s effigy for evil purposes. The woman stood trial and was executed by drowning in the Thames. Her son escaped from London and was sentenced to lifelong banishment under penalty of death. The land that the widow managed was transferred to the injured neighbour, which raises suspicions about the accuser’s real motives.

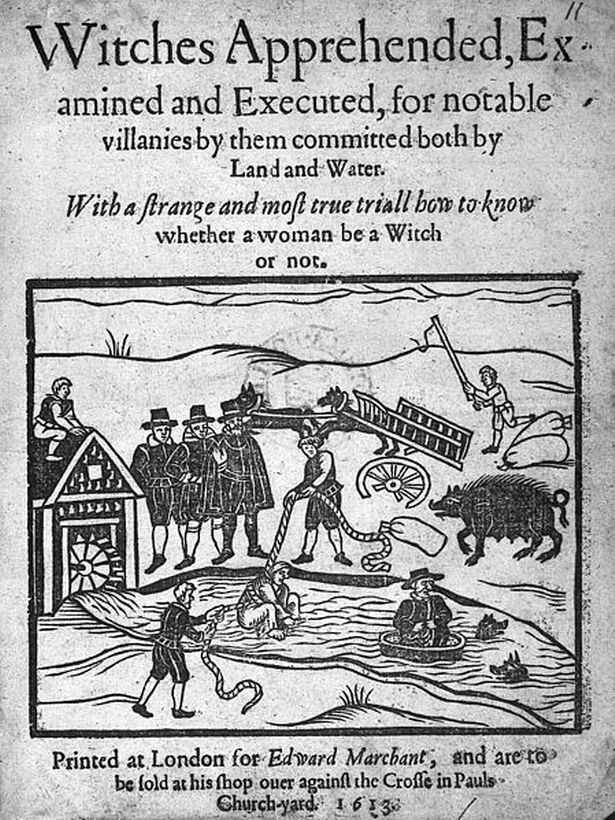

Drowning was a common method of “testing” witches. The accused would have their right thumb tied to their left toe and be thrown into the river. If they floated, it was believed they were guilty and had escaped death through black magic. If they sank, their name was cleared – but of little comfort, as the unfortunate victim was dead. Women, due to their long, flowing garments, often floated and were found guilty.

Executions in the capital were also carried out by hanging, rather than burning at the stake as was popular in Scotland and Europe. Documented cases of burning usually concerned witches accused not only of magic, but also of other crimes, most often high treason, heresy or poisoning. After death, those convicted of witchcraft often had their knees pierced with iron rivets to prevent them from rising from the grave.

Witchcraft Among Men

In 1331, a man from Southwark appeared before the King’s Court on charges of practising witchcraft, allegedly with the consent and participation of his client and an associate. The defendants claimed they used image magic to win someone’s friendship. Yet the jury concluded that the trio intended murder. Unfortunately, historical records do not reveal what punishment, if any, was imposed.

In 1371, the royal court held another man from Southwark on trial, accused of invocation and incantation. Despite finding a spell book, a human skull and a severed head of a corpse intended to be used to trap a demon, the necromancer was released from custody on the condition that he would not try to perform magic again.

In 1390, John Berking was arrested for trying to predict the future. This crime was very serious in the eyes of the clergy, and the fortune teller was sentenced to two weeks in prison, an hour in the pillory and the obligation to leave London forever.

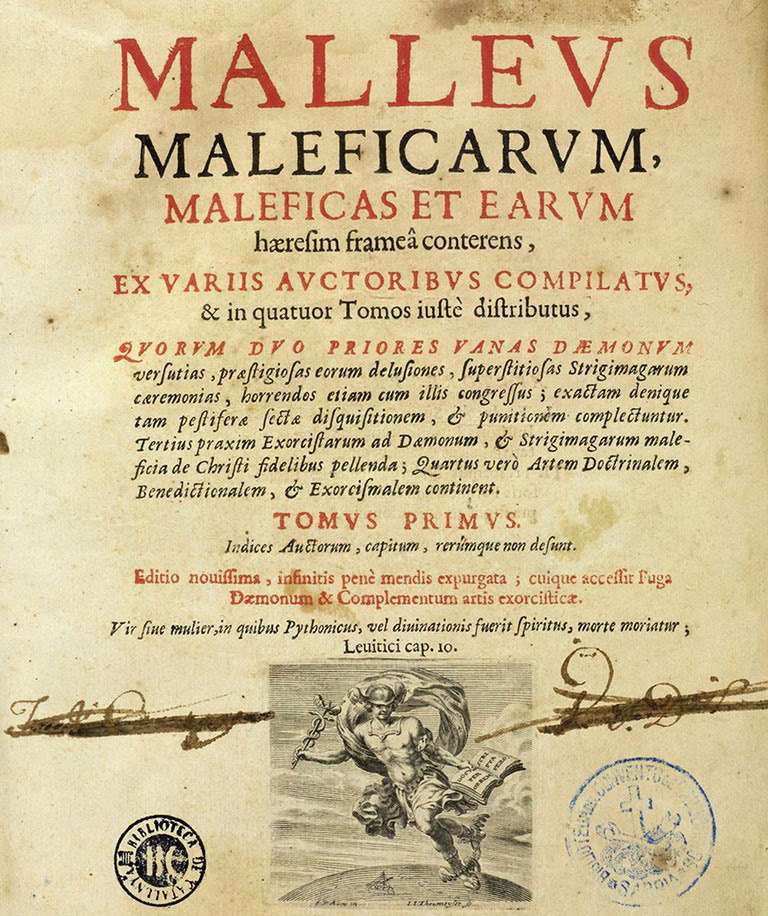

These examples demonstrate that men accused of witchcraft in medieval London often received far lighter punishments than women, who rarely escaped execution. The Malleus Maleficarum, a 1486 treatise on identifying and interrogating witches, stated:

“Women, when ruled by a good spirit, are most perfect in virtue, but when ruled by an evil spirit, indulge in the worst vices.”

This inequality often contributed to the tragic fate of many innocent women. The following cases illustrate the grim contrast in the treatment of male and female witches in London.

Margery Jourdaine: The Witch of Eye

Contrary to popular belief, witches were rarely burned at the stake in England – but one exception proves the rule. Margery Jourdaine, the Witch of Eye, was a fortune teller first detained in 1432 alongside two priests for practising forbidden rituals. Charges were dropped, and Margery was released on bail.

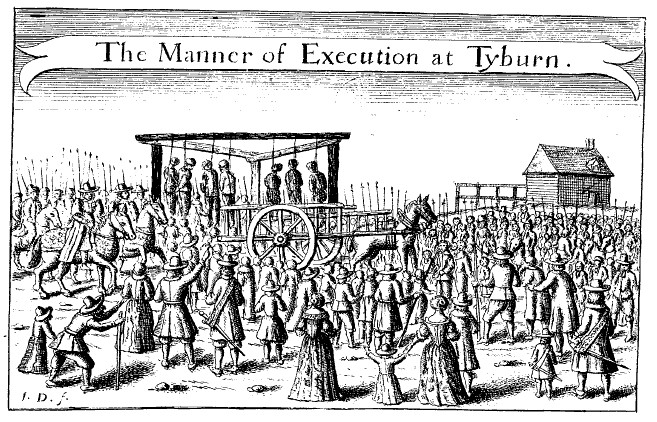

Nine years later, in 1441, Margery and four others were arrested for conspiring to assassinate Henry VI through witchcraft. At that time, high treason was the most serious offence in England, so there was no possibility of bail. Margery was burned at the stake in Smithfield, a famous execution site next to the city’s meat market. Her accomplice, Roger Bolingbroke, was hanged and quartered at Tyburn, near modern-day Marble Arch. Margery’s trial and execution were immortalised by William Shakespeare in his play about Henry VI.

Anne Kerke: London’s First Legal Witch Trial

The first legal witch trial in London took place in 1599, when Anne Kerke was convicted and hanged within five days, even though the Bishop of London was not convinced of her guilt. One day, the alleged witch had an argument with an acquaintance on the street. Following the incident, the woman’s child let out a terrible scream, froze, and died. Her second child suffered a fit of spasms but recovered as soon as Anne departed. Kerke was also accused of bewitching another child, allegedly because she had not been invited to the baptism. The infant recovered when one of the neighbours advised the parents to burn a piece of Anne’s coat alongside the child’s nappy.

Shortly thereafter, Anne was reported to the magistrate. Judge Sir Richard Martin heard that witches’ hair did not burn, so it was decided to cut off her locks to conduct a trial by fire. Her hair allegedly dulled and spoiled the scissors, which was considered sufficient evidence of guilt. Anne was brought to trial on November 30, 1599, and received the death sentence on the same day. She was executed by hanging on December 4, at Tyburn.

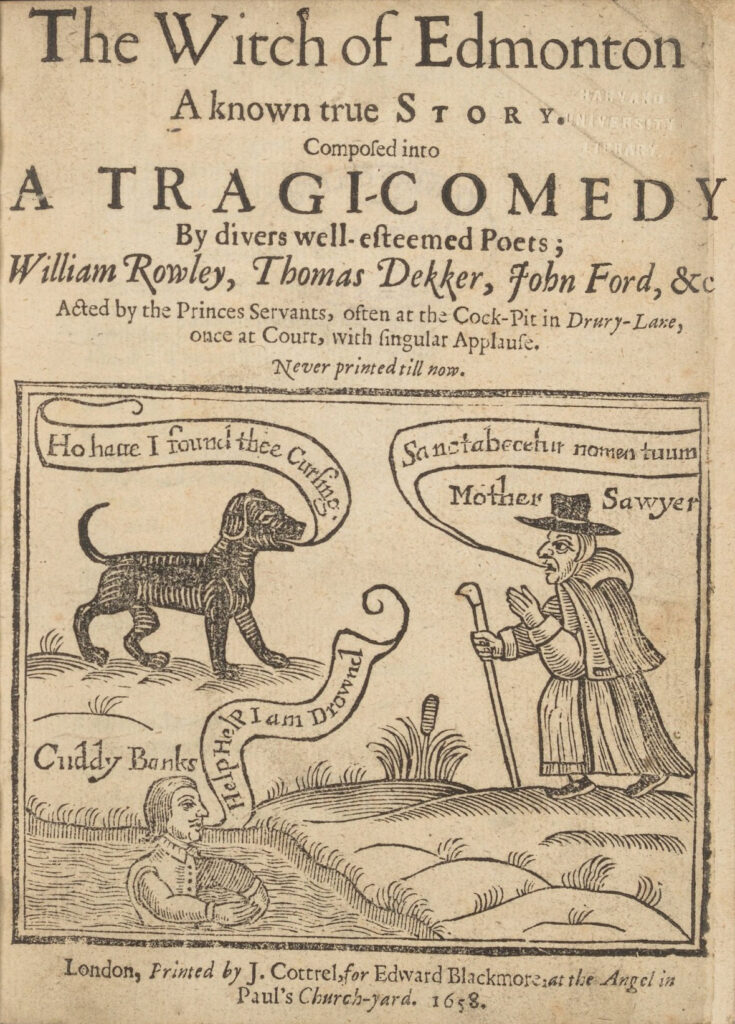

Elizabeth Sawyer: The Witch of Edmonton

One of the most infamous witchcraft trials in London was that of Elizabeth Sawyer in 1621. An Edmonton witch and resident of Winchmore Hill, she was accused of causing the death of Agnes Ratcleife by magic, after Ratcleife had struck one of Sawyer’s pigs for eating her soap. Yet rumours of Elizabeth’s witchcraft had been circulating long before the accusation. Known for her swearing and blasphemy, she had already aroused suspicion among the locals. It was said that one day a demon in the form of a dog, named Tom, appeared to her and tempted her with promises of serving Satan. Thereafter, the devil reportedly visited her thrice weekly as a familiar, sometimes appearing black, sometimes white.

Local women were summoned by the court to search for a witch’s mark on her body – a birthmark or other distinctive token. They returned with the shocking report that they had discovered a large discoloration near Elizabeth’s anus. This finding strongly influenced the jury, who convicted her. Elizabeth was subsequently hanged at Tyburn. Her story appeared on the city’s book stalls within days and was soon adapted for the stage.

John Lambe: The Royal Enchanter

Around 1600, John Lambe gained a notorious reputation for astrology and magic. Though he was not a licensed physician, he was credited with predicting the future, diagnosing illnesses, countering spells, and recovering lost or stolen items using a crystal ball. Rumours also suggested that he dabbled in dark enchantment.

Despite skirting the boundaries of heresy and witchcraft, Lambe became the personal advisor to George Villiers, favourite of King Charles I, in 1625. Opinions about him, however, remained sharply divided: some dismissed him as a mere charlatan, while others believed he possessed genuine supernatural powers.

Despite repeated attempts by Londoners to punish Lambe for practising black magic, his connections at the royal court protected him. In 1627, he was tried for the rape of an eleven-year-old girl and sentenced to death, but the execution was repeatedly postponed. On 13 June 1628, a frustrated crowd took matters into their own hands and stoned Lambe to death near St Paul’s Cathedral. No one was ever held accountable for his murder. Less than two months later, Villiers himself was assassinated. In 1653, Lambe’s former maid, Anne Bodenham, was hanged for witchcraft, accused of summoning demons and transforming into a range of animals.

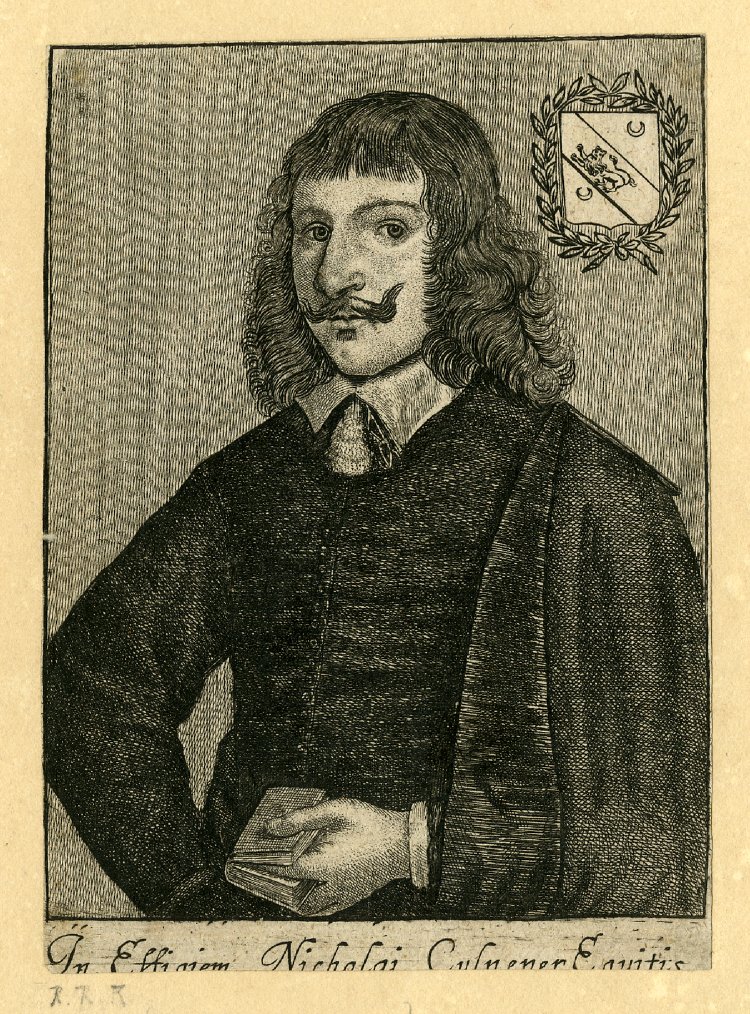

Nicholas Culpeper: Herbalist and Natural Philosopher

Nicholas Culpeper, a doctor and herbalist from Shoreditch, faced accusations of witchcraft in 1643 from his patient Sarah Lynge, who claimed that one of Culpeper’s devilish tricks had caused her slow decline. In reality, Culpeper was instrumental in democratising medical knowledge, making it accessible to a wider audience. A political radical, he ran a pharmacy from his home in Spitalfields, outside the jurisdiction of the City of London, and translated Latin medical texts used by the Royal College of Physicians into English.

Culpeper’s herbal research was guided by astrological observations. His 1652 publication, Culpeper’s Complete Herbal, still in print today, details both the cosmic properties and medicinal benefits of plants. In the 17th century, the boundaries between magic, religion, and science were blurred. Natural philosophers such as Sir Francis Bacon and Culpeper combined logic, medicine, and botany with experiments in alchemy, astrology, and divination. Eventually, the 1643 accusations of black magic were withdrawn, and Culpeper was acquitted. One might well wonder whether his fate would have been the same had he been a woman.

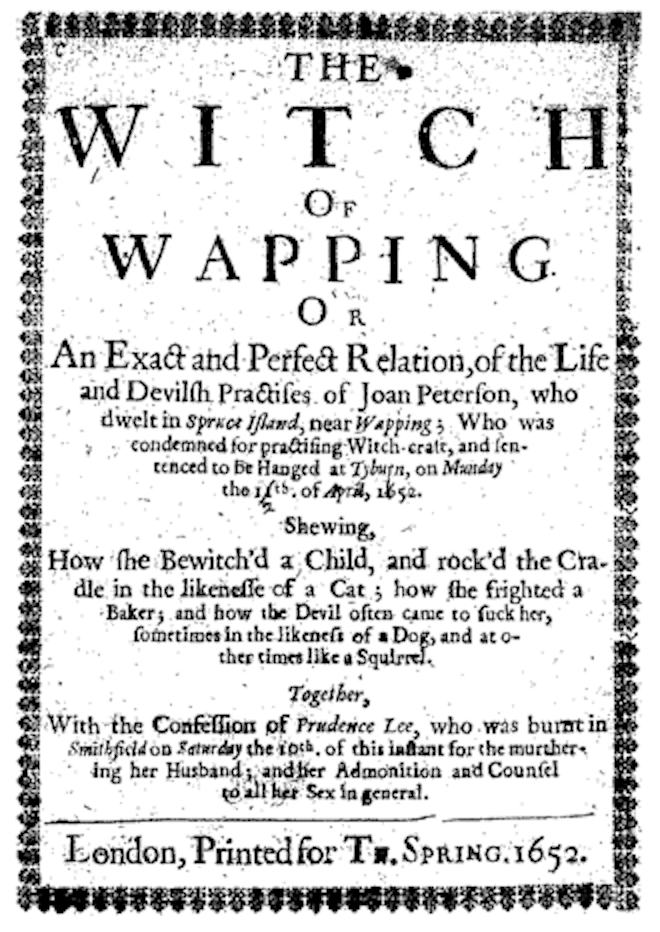

Joan Peterson: The Witch of Wapping

Joan Peterson, known in Wapping for her herbal remedies, shared a practical knowledge of healing with Culpeper but became embroiled in a notorious case following the death of Lady Mary Powell in 1652. Surprisingly, Powell’s estate had passed to an unrelated Anne Levingston, and Peterson was accused of using a spell to cause Powell’s death. Rumours claimed she could transform into a black cat, was seen conversing with a squirrel, and was said to have caused spasms in a baker who owed her money. Friends and neighbours protested her innocence, and a doctor testified in court that Powell, then in her eighties, had likely died of natural causes.

Peterson was offered a pardon if she testified against Anne Levingston and her alleged witchcraft, which might have secured Powell’s inheritance for her. Joan refused to comply – and reportedly struck one of her accusers in the face. She was sentenced to death and executed by hanging at Tyburn on 12 April 1652. This remains the last recorded execution for witchcraft in London.

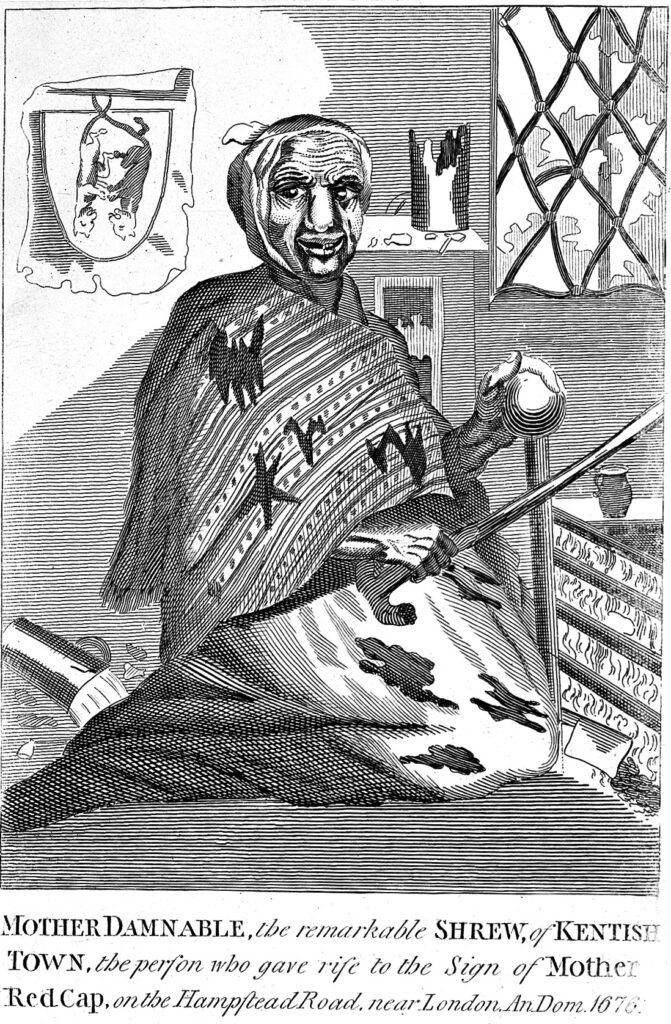

Jenny Bingham: Witch Queen of Kentish Town

Jenny Bingham, also known as Mother Damnable or Old Mother Redcap, was one of London’s last witches, residing in Camden in 1676. She gained a fearsome reputation, as all of her lovers reportedly died under mysterious or gruesome circumstances – one was even said to have been found burned in her large kitchen stove. Jenny frequented London’s taverns wearing a red cap fashioned from a musketeer’s belt, offering her magical remedies to those bold enough to seek them.

Dubbed the Witch Queen of Kentish Town, she was never convicted – perhaps because locals relied heavily on her medicines or feared the repercussions of accusing her. Jenny was eventually found dead in her home alongside her black cat; both had ingested tea brewed from poisonous herbs. Her house stood at a crossroads, most likely at the site of the modern World’s End pub or Camden Town tube station.

The Trial of Jane Kent

In the 1680s, witchcraft trials persisted in London, usually centred on suspicions of causing another person’s illness or death. In 1682, the Old Bailey heard the case of Jane Kent, accused of allegedly casting a fatal spell on a five-year-old girl, Elizabeth Chamblet. The magistrate was told that Elizabeth had “fallen into a deplorable condition and swelled up all over her body, which quickly became completely discoloured” before she died. Distraught over his daughter’s death, Elizabeth’s father blamed Jane Kent for witchcraft, particularly as they had previously argued over a failed pig sale.

Kent was eventually acquitted and released. During the trial, numerous witnesses testified to her good character and regular church attendance. The mysterious ailment that afflicted Elizabeth Chamblet remains unexplained.

Witches during World War II

One might think that witchcraft vanished along with the mediaeval stakes, the superstitions of uneducated peasants, and the dwindling number of devout Christians – Anglicans and Catholics alike – in Britain. Yet nothing could be further from the truth. London’s association with witches and magic did not end in the 17th century, but continues to this day.

From 1735, being a witch was no longer a crime in Britain – but impersonating one still was. Remarkably, even during World War II, two women were convicted under this old 18th-century law. Jane Rebecca Yorke, a medium based in Forest Gate, was accused of deceiving the public and exploiting wartime fears. She was arrested and found guilty on seven counts, due to her extensive – and seemingly inexplicable – knowledge of war matters, which she openly shared with her clients.

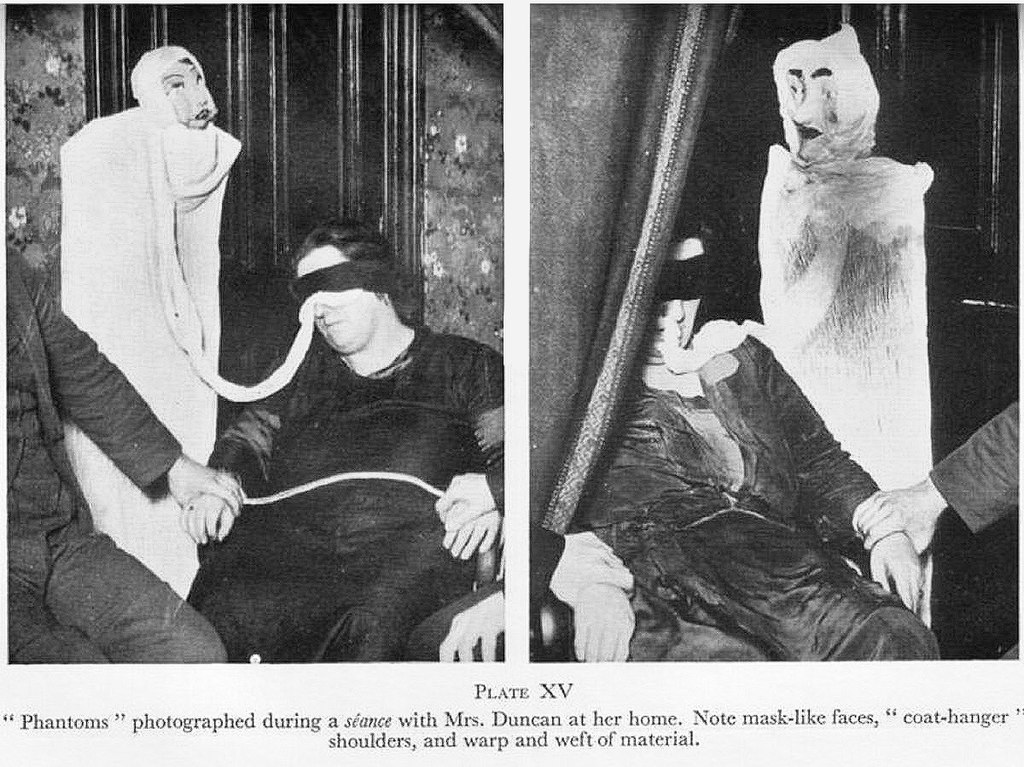

The last known trial under the 1735 Act concerned Helen Duncan of Scotland in 1944. She was accused of conjuring the spirit of a sailor in a Portsmouth church; the sailor had died when his ship was sunk by a German U-boat in 1941. Arrested during her second spiritualist séance with the sailor’s spirit present, Duncan was branded a traitor, and her actions deemed harmful to war morale. Although Winston Churchill dismissed the case as ‘tomfoolery’, no steps were taken to release or pardon her.

Father Wicca and the Nazis

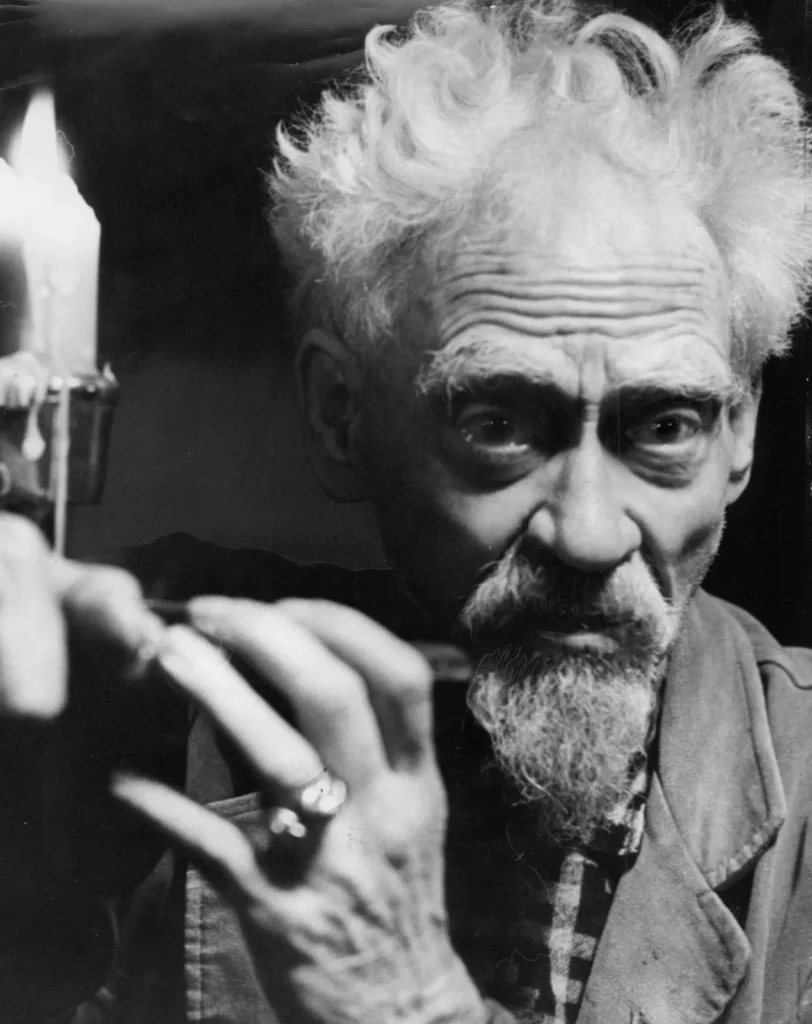

During World War II, Gerald Gardner—later known as the Father of Wicca—sought to revive the ancient pagan religion of Wicca from his Charing Cross apartment. With his striking grey hair and black cape, he could easily be mistaken for a genuine wizard. A retired civil servant, Gardner had moved to London in 1938 with the goal of restoring Britain’s pagan witchcraft traditions, eventually helping Wicca gain recognition as an official religion in Great Britain.

As a member of the secretive New Forest Coven, Gardner reportedly attempted to counter Nazi aggression in 1940 through magical means, targeting Adolf Hitler’s mind in an operation dubbed the “Cone of Power.” Despite his mystical efforts, the Luftwaffe’s raid on London that year proceeded as planned, leaving Gardner’s magic powerless to alter the course of events.

Contemporary London witches

Witches and magicians have survived into modern times, though they’ve long since traded dried frogs and herbal potions for mass-produced cauldrons and polyester capes. Nowadays, people looking for their witchy vocation should go to south London, and especially to Croydon, which statistically has the largest concentration of witches in Great Britain. According to the Office for National Statistics’ 2011 census of religions, a sizable group of residents in the area described their religious beliefs as Wicca. There are several shops in Croydon selling magical crystals and herbs, as well as astrologers, tarot readers, witches for hire and a suspicious number of people in long, flowing dresses and cloaks.

Until recently, the annual Witchfest International was also held here – the largest witchcraft festival in history. Unfortunately, the celebrations have now moved to a new, cheaper venue in Brighton. Proof that even witches are powerless against rising rents in London. The second popular location for modern witches is the St Giles and Bloomsbury areas, where there are several occult bookstores specialising in spell books and the history of witchcraft, as well as a well-stocked astrology shop.

Discover more from London Macabre

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.