Completed in 1703, St Thomas’ Church is a most unusual – and yet almost entirely forgotten – part of London, home to the Georgian operating theatre hidden in its attic. It sits awkwardly pressed between a row of tight terraced houses and a sperm bank, dwarfed on one side by the glass bulk of the Shard and on the other by the hungry stream of Londoners perpetually grazing at Borough Market. What remains is a curious patchwork of faded history, former splendour and modern marketing whimsy, its nave now taken over by a kitschy dance club for giggling thirty-somethings.

Few of the tourists wandering through London Bridge and Southwark spare its modest tower even a passing glance. Yet a narrow, twisting staircase invites the brave to climb upwards into the roof space. Here, far from the clamour of the streets, hides Europe’s oldest surviving operating theatre, complete with a medicinal herb garret, apothecary, and a small museum of anaesthesia and surgery. The creaking boards, the scent of lavender and cloves, the handsome timbered ceiling and the resident skeleton known as Mrs Grieve could well sweep you back two centuries – if it weren’t for the insistent thump of techno rising from the overheated dancefloor below.

A Hospital Through the Ages

The history of this hospital is unusual, vivid and astonishingly long. It survived two relocations, several outbreaks of plague, repeated waves of cholera that ravaged the poor of Southwark, mercury cures administered to the syphilitic, and eventually the arrival of anaesthesia and the recognition of nursing as a profession in its own right. Even now it stands among the most prestigious hospitals in the country, its legacy marked by numerous world firsts – including the earliest successful implantation of an artificial eye lens.

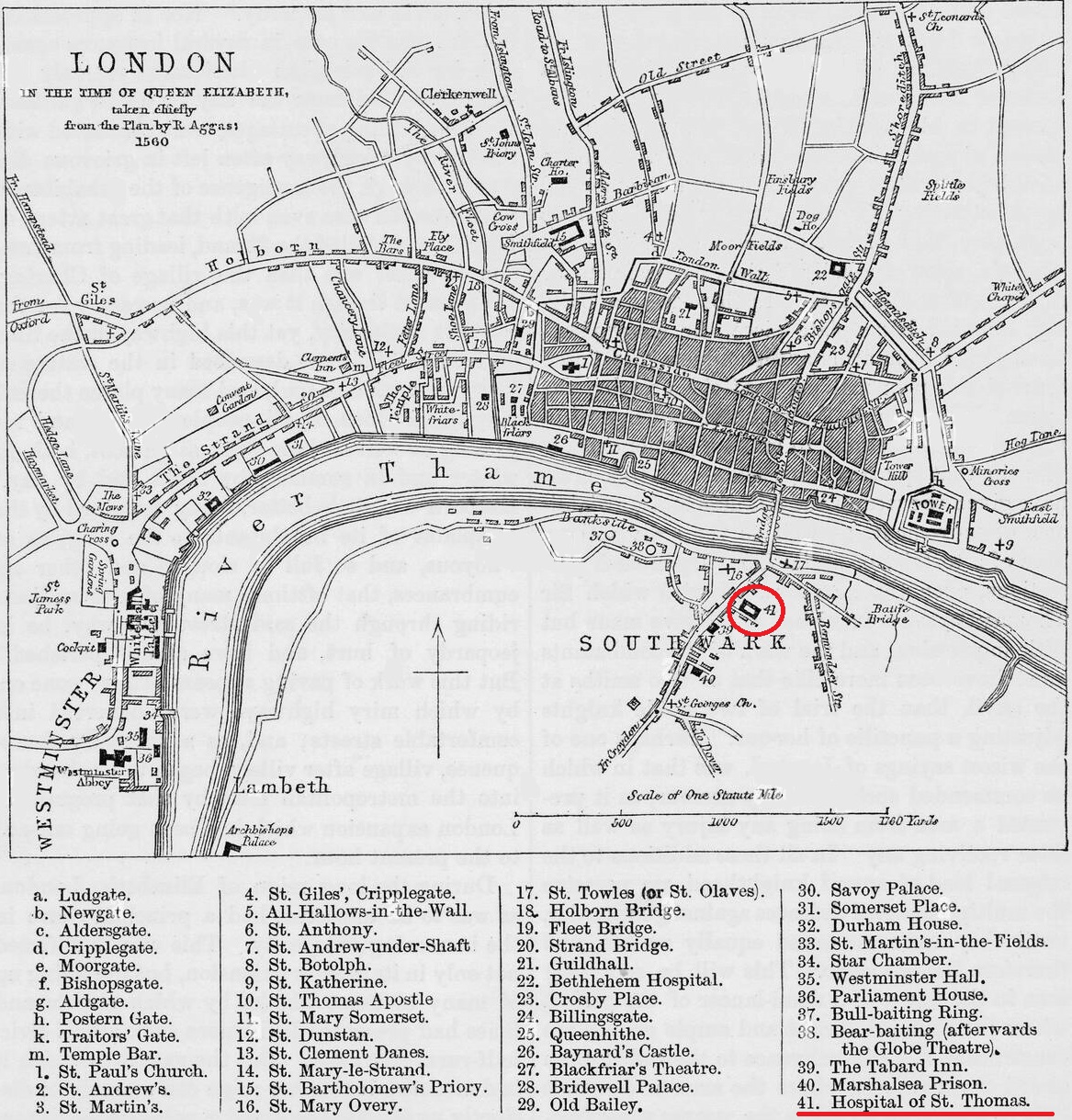

St Thomas’ Hospital was founded around 1173 by Augustinian canons of the Priory of St Mary Overie – today’s Southwark Cathedral – in honour of St Thomas Becket, murdered in Canterbury Cathedral just three years earlier. It is one of the oldest hospitals in Britain. After the great fire of Southwark in 1212, the hospital was moved to St Thomas Street, where it remained for more than six and a half centuries. Its mission was simple yet vital: to shelter and care for the poor, the sick, and the homeless. Astonishingly, as early as the fifteenth century the hospital also housed a ward for unmarried mothers – a remarkably progressive act for its time.

Renaissance and Rebirth

The upheavals of the 16th century proved decisive. Following Henry VIII’s severance from Rome and the dissolution of the monasteries, the hospital – still under the governance of the Catholic priory of St Mary Overie – was closed in 1541. Twelve years later, in 1553, the City of London revived it and renamed it St Thomas the Apostle, aligning it with the Anglican tradition. Restored to life, the hospital offered 284 beds and was staffed by skilled physicians, surgeons and apothecaries, as well as a treasurer, a steward, a matron and several ward sisters. At the same time, its now-famous medical school was established.

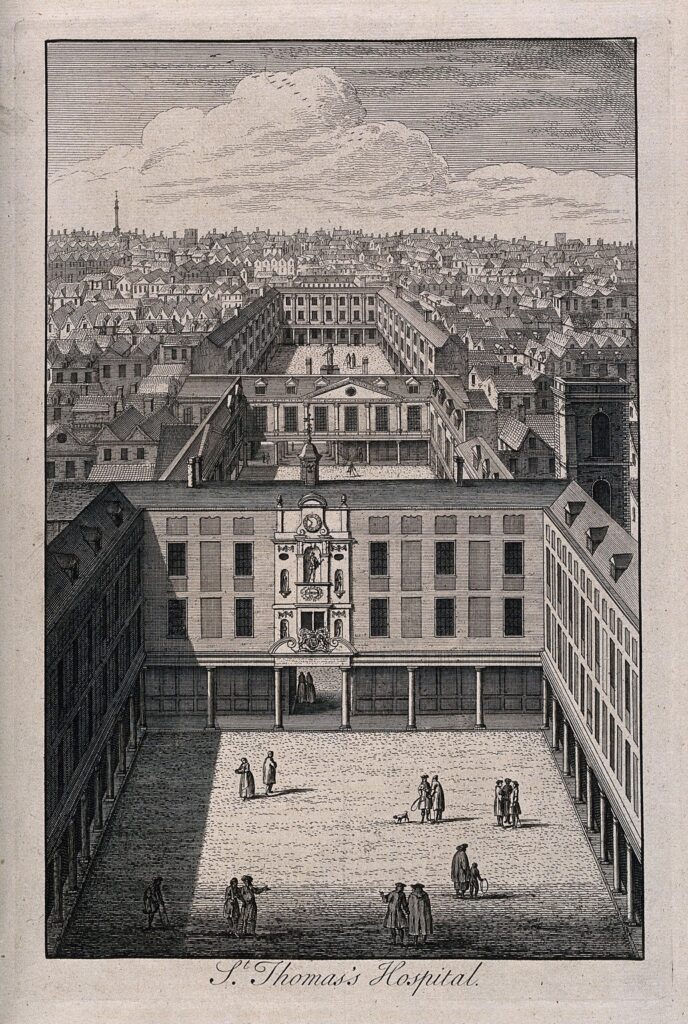

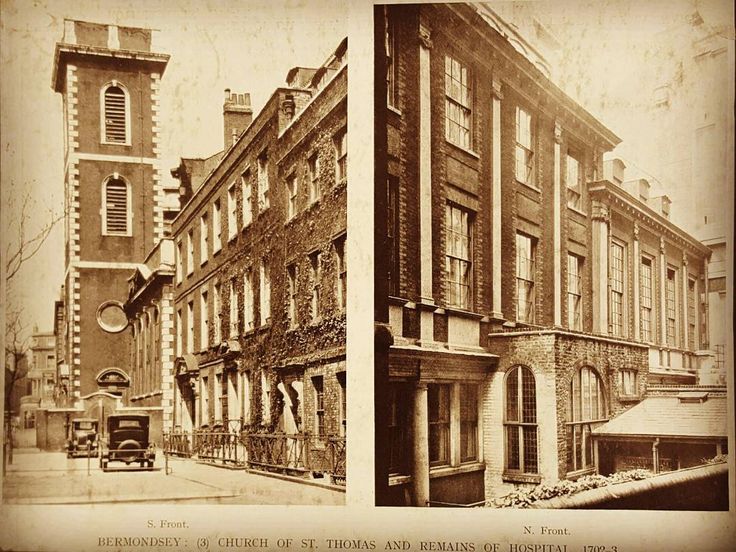

By the end of the 17th century, the old buildings had decayed and patient numbers had swelled far beyond capacity. Between 1693 and 1702 the entire hospital underwent a sweeping reconstruction. Its size tripled, with 19 wards located in three-storey buildings enclosing three quiet courtyards, and with the rebuilding of St Thomas’ Church, completed in 1703.

The church was not merely adjacent but absorbed fully into the hospital complex – a decision that would later set the stage for an operating theatre to be created in its attic, conveniently level with the women’s ward. But that moment lay still ahead. For now, from 1703 onwards, the attic served the apothecaries as a place to dry herbs and store medicinal supplies. In time, it came to be known as the Herb Garret.

The Herb Garret

At first, the attic was intended simply as storage for the hospital. Yet the apothecaries of St Thomas’ soon pressed for it to be given over to them as a place to dry herbs and prepare their medicines. Nestled between the oak rafters, the plants dried quickly as the warmed wood drew out their moisture, and the height of the space kept them safely beyond the reach of insects and other pests. The apothecaries lodged nearby on St Thomas Street, making the attic all the more convenient.

And so, for more than a century, the church loft served as the hospital’s herb garret. Quantities of herbs were purchased from a visiting “herb woman”. The hospital also had its own medicinal garden and an apothecary’s workshop and shop within its grounds.

A Pharmacy in the Rafters

Wandering through the museum today, it is easy to picture those quiet, bent-backed pharmacists at their work, carefully weighing herbs and tinctures on delicate brass scales. The shelves beneath the windows are lined with an assortment of dried plants – flowers, fruits, bark, roots and other remnants of a once-vital pharmacopoeia – each labelled with its former medicinal use. Basil, oregano, dried oranges, cinnamon, cloves, mint, aniseed and, of course, lavender all sit waiting, as if the apothecaries themselves had only just stepped out.

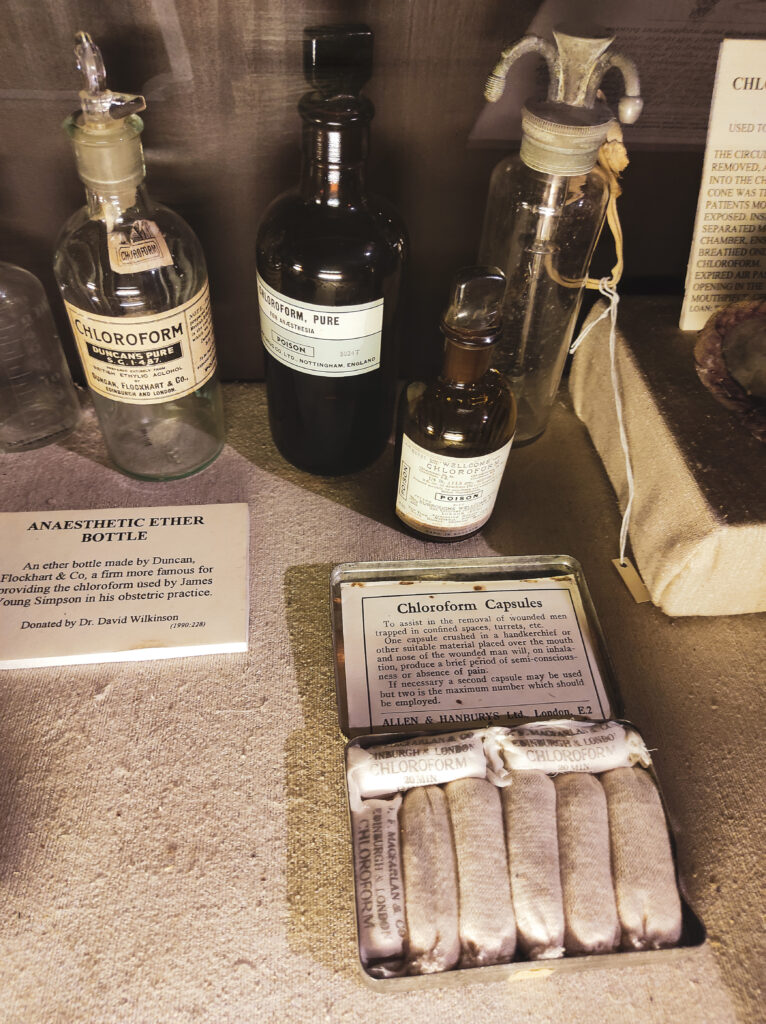

Yet the most besieged and tirelessly photographed cabinet is the one that houses remedies now forbidden in medicine. Behind its glass rest large, desiccated poppy heads, discovered beneath the floorboards in the 1970s. Their latex was once used to make laudanum, the potent solution administered during painful procedures before the advent of anaesthesia in 1846. It is worth noting that laudanum was given to soothe patients only after surgery – operations themselves were still performed entirely without anaesthetic. In that same cabinet stand original bottles of morphine, cocaine, ether, chloroform, strychnine, heroin and mercury: a small, chilling archive of the tools once relied upon in mainstream medicine.

Development of Surgery in the Hospital

The first operating theatre at St Thomas’ Hospital was established for the men’s ward in 1755. In 1813, the governors resolved to create a separate northern annex dedicated to a new university programme intended to train the next generation of surgeons. This annex contained a lecture hall, an anatomical operating theatre, a room for post-mortem dissections, and a pathology museum. By 1822, it was the women’s turn: a purpose-built operating theatre for female patients was finally commissioned.

Before the creation of the women’s theatre, operations on female patients took place directly on the ward among the other occupants. The “procedure room” was simply a curtained-off corner. The pain and cries of a patient held down by several assistants – the hurried instructions, the clatter of instruments – were not only heard by the terrified women lying just a few feet away, but often seen, in the form of blood on aprons and floors. The construction of a dedicated operating theatre was therefore not merely a practical improvement for surgeons but an act of mercy for the patients themselves.

Into the Women’s Theatre

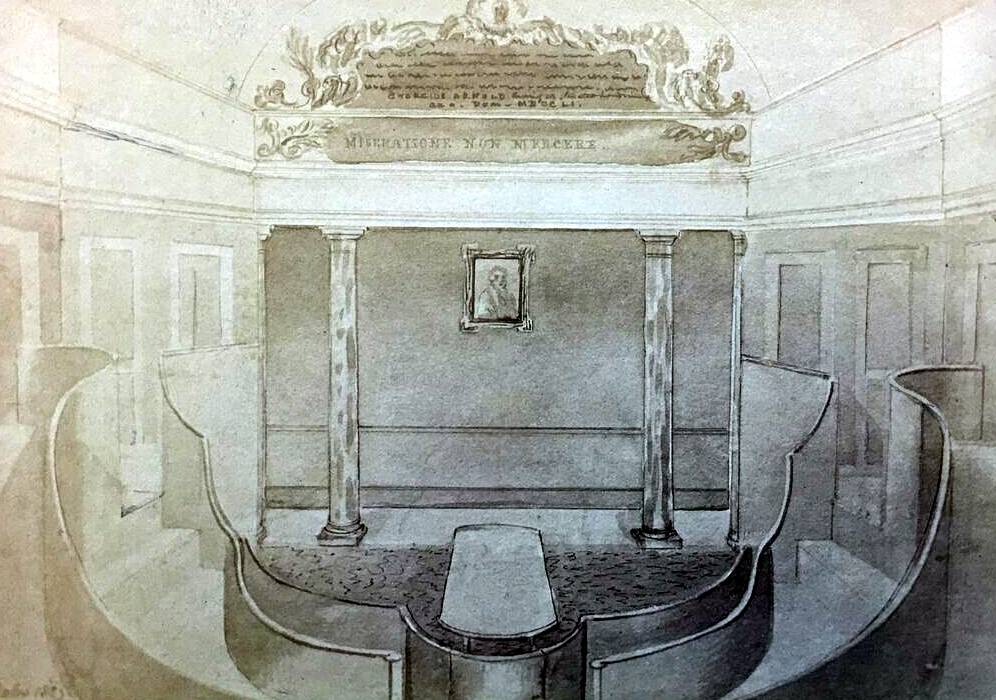

Dorcas Ward, the women’s quarters of the hospital, shared a wall with the attic of St Thomas’ Church. The hospital administration therefore decided to pierce a set of double doors at the end of the ward and convert the former herb garret into an operating theatre with an adjoining post-operative recovery room. Thankfully, someone had the foresight to propose this arrangement; had the theatre remained within the main hospital buildings, it would have been lost forever when the entire complex was demolished to make way for London Bridge Station.

The new theatre was fitted with steps and galleries from which young surgical apprentices could observe their more experienced colleagues, learning from both their failures and their triumphs. A large skylight was cut into the roof, flooding the room with natural daylight and giving surgeons the best possible chance at precision in an era before electricity.

Blood, Sawdust and Screams

Climbing the narrow stairs into the theatre and looking down upon the wooden operating table – with its box of sawdust beneath to catch the blood – one is struck by a strange sensation. With the creak of the steps, the unnatural hush where agonised screams once echoed, and the slow drift of dust motes in the light, visitors instinctively lower their voices, as if entering a place of worship.

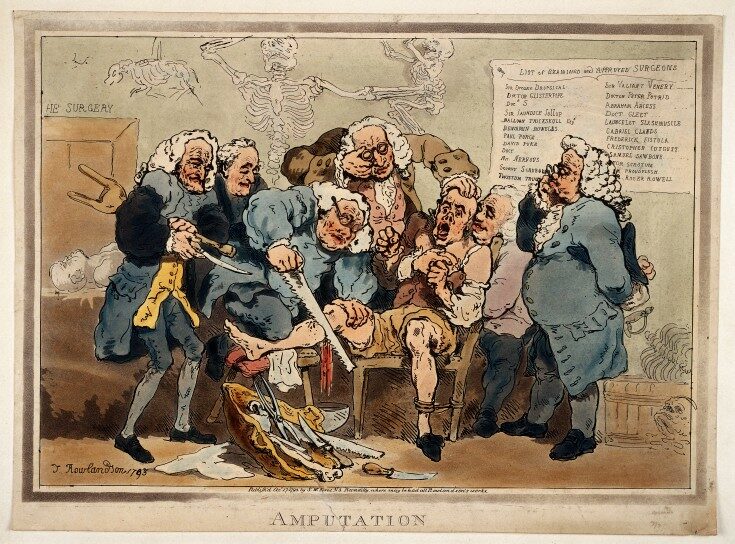

It was here that surgeons waged their desperate battle to preserve human life without the benefit of anaesthesia or antiseptics. Among the objects on display is a stout physician’s cane, ordinarily used for support, but during operations pressed between the patient’s teeth as a makeshift gag. Deep imprints of molars still scar its sides. Elsewhere in the theatre lie trepanning sets, instruments for removing bladder stones, and the saws and knives used in amputations – the only procedures, aside from complicated births, that surgeons attempted in this room.

Because of the unbearable pain, surgery was undertaken only when all other options failed, and the golden rule was that it must be completed in under two minutes to minimise blood loss and shock. Mortality rates at St Thomas’ hovered around 30 per cent, yet many patients accepted the risk, clinging to the hope of survival. Most deaths arose from shock, haemorrhage, or infection – a highly likely consequence of unwashed instruments, unclean hands, and a theatre untouched by disinfectant.

Common Procedures

Trepanning was among the oldest forms of surgery. The procedure involved boring a hole into the skull to relieve intracranial pressure or remove fragments of shattered bone. A strong assistant gripped the patient’s head immovably, while others restrained their arms and legs; sometimes the limbs were tied with ropes to keep the body still.

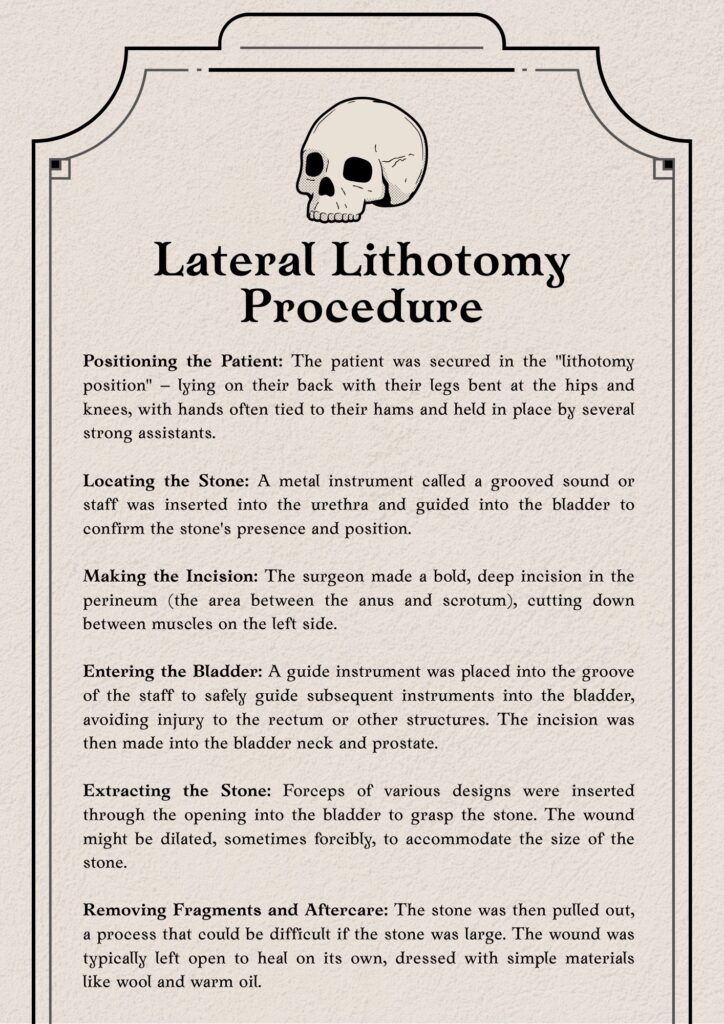

If that sounds excruciating without anaesthesia, consider lithotomy – the surgical removal of bladder stones. These stones were notoriously common among London’s poor due to their diet and could grow to the size of a hen’s egg, often proving fatal. William Cheselden, one of St Thomas’ most renowned surgeons, achieved fame by refining the operation and reducing its duration from forty minutes to a mere sixty seconds. His improvements raised the survival rate to an extraordinary 92 per cent.

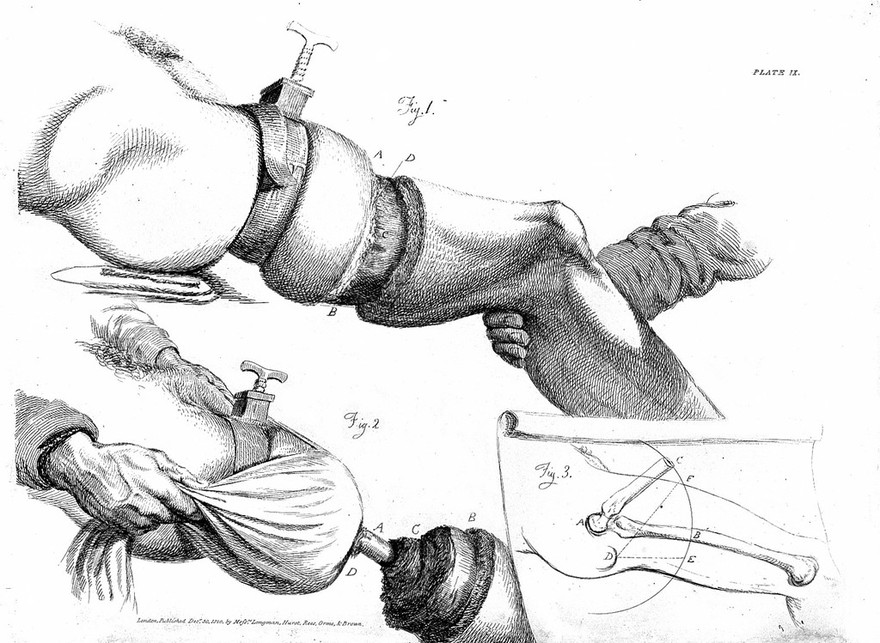

Amputations, by contrast, carried a far greater risk of death due to the brutality and scope of the procedure, yet for many injuries, infections, or cases of gangrene, they were the only chance of avoiding a swift demise. Surgeons used knives and saws to sever limbs, and until the late sixteenth century the bleeding stump was cauterised with boiling oil or red-hot irons. This barbaric practice gave way only after Ambrose Pare pioneered the use of ligatures. In time, surgeons began using skin flaps from the severed limb to cover and stitch the wound – a technique that still forms the basis of modern surgical practice.

Gynaecology & Obstetrics

In a shadowed corner of the museum, another glass case contains instruments once used in the hospital’s obstetric procedures. Although childbirth remained the domain of midwives well into modern times, from the eighteenth century onwards physicians increasingly intervened in difficult deliveries.

The sheer size of some instruments – designed either to assist birth or to remove a deceased foetus – can make one’s stomach tighten and knees weaken. Methods of forced abortion in cases of foetal death recall the grim contraptions of medieval torture chambers, while the cold, steel speculum could easily belong in a scene from a sci-fi movie. These tools were kept strictly hidden from female midwives and reserved for male surgeons for more than a century. Some, in refined and safer forms, remain in gynaecological use today.

Anaesthesia Arrives

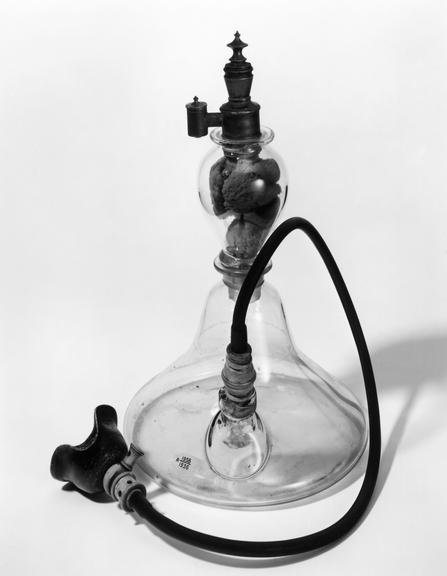

For centuries, alternative methods of dulling pain – such as opium or alcohol – were used by physicians to blunt, however slightly, the agony of surgery. Doctors also relied on other measures: freezing limbs, compressing nerves, administering nitrous oxide, and even attempting hypnosis. Yet operations remained a form of torture until two new substances were discovered: ether in 1846 and chloroform in 1847. These anaesthetics permanently transformed both the patient’s experience and the medical approach to surgery and physical pain.

The first recorded use of ether is attributed to an American dentist, William Morton, who shared his discovery with doctors at Massachusetts General Hospital. News of the miraculous innovation travelled quickly to London. In December 1846, Robert Liston performed the first amputation under anaesthesia at University College Hospital. At St Thomas’ Hospital, the first ether procedure followed in January 1847.

Around the same time, Dr James Simpson, Professor of Midwifery in Edinburgh, identified the anaesthetic qualities of chloroform. From that moment, anaesthesia was formally introduced into medical practice. London physician John Snow, best known for proving that cholera was a water-borne disease, was also a respected anaesthetist who administered ether to Queen Victoria during the birth of one of her children.

The benefits of anaesthesia were clear: patients no longer had to endure terror and unbearable pain, which often sent them into postoperative shock. Surgeons no longer needed to rush through procedures; they could work with greater precision and undertake more complex operations, including those involving internal organs. But there were grave drawbacks. Anaesthesia did not arrive hand-in-hand with antiseptics. The patient’s body was exposed to bacteria for far longer, increasing the risk of infection and complications. Ether and chloroform were also treacherous to administer: an excessive dose could prove fatal, while too little could cause the patient to regain consciousness mid-operation.

The Dark Side of Medicine

The old operating theatre in the attic of St Thomas’ Church never lived to see the antiseptic era during its forty years of use. The practice of killing germs on surgical instruments, wounds, the operating table – or even the surgeon’s hands – was entirely unknown. Tools were rarely cleaned beforehand, bandages were routinely reused, and hands were typically washed only after the procedure. Surgeons operated in their everyday clothes beneath a white apron that was never changed; the more it was stiffened with dried blood, the greater the surgeon’s reputation and the patient’s confidence.

Operations were almost always performed before an audience of medical students eager to crowd as close as possible to the patient. According to reports from St Thomas’ Hospital, as many as 150 people sometimes squeezed into the small room. Unsurprisingly, postoperative infection – known as “hospital fever” – was the leading cause of death.

Only the work of Louis Pasteur in the 1860s, proving that bacteria caused disease, prompted change. The renowned surgeon Joseph Lister developed the first effective antiseptic methods in 1864, introducing a spray of carbolic acid (phenol) during surgery to disinfect the air and instruments. Thanks to phenol, he reduced his patients’ mortality rate from 46% to 15% in just three years.

A Quiet Witness: Mrs Grieves

Before you leave the old operating theatre, and begin feverishly scanning the museum shop shelves – convincing yourself, with increasingly flimsy arguments, that you definitely need five hefty books of medical history – you should spend a few minutes with the rather lonely Mrs Grieves.

Mrs Grieves is the skeleton of a nineteenth-century woman, displayed in a case beneath the window. She was recently subjected to a detailed analysis of her bone structure in the hope of uncovering clues about her origins and the life she led. We now know that she was around 161 cm tall and died between the ages of twenty-four and thirty-two. Her teeth show clear signs of childhood periods of starvation, and her diet appears to have consisted largely of fish – typical of the Victorian working classes. Further examination revealed anaemia and a vitamin D deficiency that caused deformities in her ribcage. The cause of her death remains a mystery.

We do not know whether she died in a hospital, a workhouse, or somewhere else entirely. What we do know for certain is that no relative or friend ever came forward to claim her body. Under the terms of the Anatomy Act of 1832, her remains could therefore be legally sold and acquired for medical study – which is precisely what happened in 1884. Give her a little wave on your way out; it must be rather dull, shut inside that glass case all day with nothing but a dissected brain and a fragment of human lung for company.

From Southwark to Lambeth

In 1862, St Thomas’ Hospital left the vicinity of London Bridge after more than six centuries to make way for the new railway station linking Southwark with Charing Cross. The hospital was moved to Lambeth, directly opposite the Houses of Parliament, where it still stands and operates today.

Soon after the departure of the last patients, the hospital buildings were levelled with barely a hint of sentiment. Almost the entire complex was demolished, save for a small cluster of structures on the north side of St Thomas Street and St Thomas’ Church itself – the only surviving fragments. The operating theatre, miraculously spared, was sealed up and forgotten for nearly a century.

Rediscovery and Restoration

Its rediscovery came in 1956, when historian Raymond Russell began investigating the attic of St Thomas’ Church. While researching the history of the neighbouring hospital, he grew curious about the unused loft space. Climbing a ladder through an opening some fifteen feet above the floor, he found himself in a dark, dust-choked room containing the remains of the long-lost theatre. Much of the plasterwork and flooring had survived, and the original structures still in place offered invaluable clues for its eventual restoration. In 1962, the space reopened to the public as a museum.

Today, it is undeniably one of those deliciously macabre museums that belongs on the must-visit list of any self-respecting admirer of medical history, pathology, or early anaesthesia passing through London – and, naturally, anyone with even the faintest gothic inclination.

Discover more from London Macabre

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.