When you wander the streets of Notting Hill, the very first thing that strikes you is the sudden shift in architecture west of Walmer Road. The pastel-coloured, well-kept nineteenth-century houses suddenly give way to bleak, bare-brick tenements and clusters of grey, battered tower blocks.

Every building looks exactly the same. Dull brickwork, plain walls, no ornate décor, no cheerful plasterwork. Cross that invisible line and the nouveau-riche, posh Notting Hill vanishes as if wiped away by a spell.

Suspecting that such a sudden and inexplicable shift might hide a forgotten secret, I dug into the neighbourhood’s past. That is how I came across the name Avernus – the old term for the notorious pocket of squalor at the heart of Notting Dale estate.

A Surge of Construction and Decline

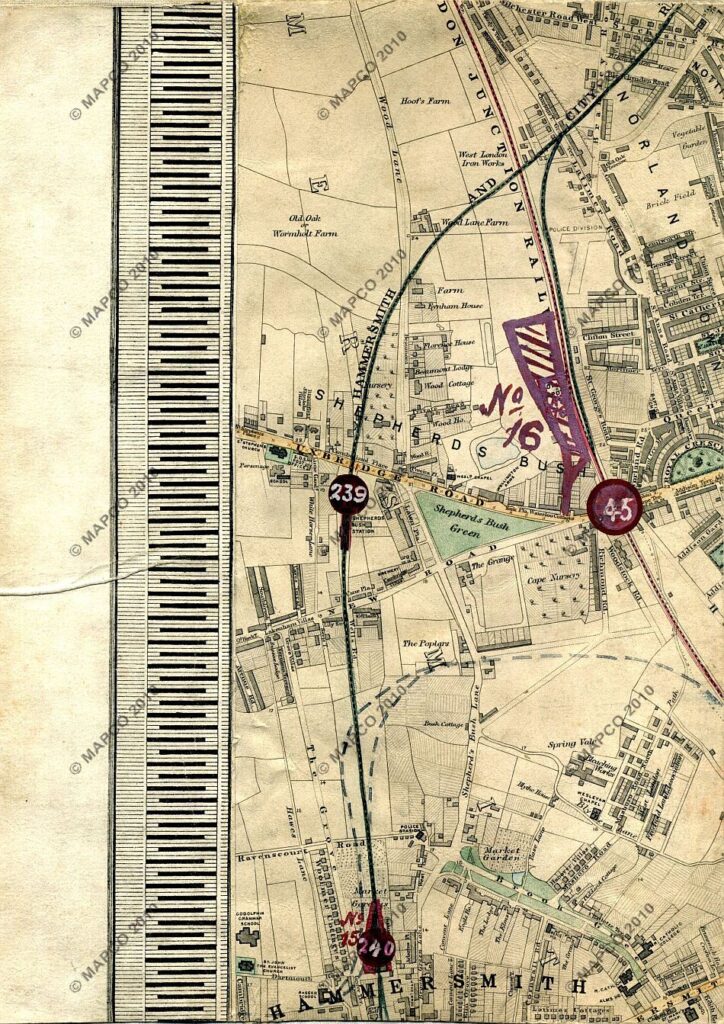

In the 1860s, London entered a period of frantic building. The growing demand for property after the economic crisis of 1847 reached the western edges of Notting Hill. In 1865, Stephen Bird, owner of one of the largest brickworks near Pottery Lane, decided to take advantage of the favourable market. He abandoned brick-making and began building houses on his old clay pit. Rows of terraced houses soon spread northwards too, on land bought by another developer, James Whitchurch.

The Birth of the Slums

Both men expected that the new railway line being built nearby would further raise land values and attract buyers. In fact, it became one of the principal causes of the slums of Notting Dale, later known as Avernus (Latin: ‘descent into hell’). The Hammersmith & City Railway opened in 1864. The line ran through Shepherd’s Bush and Notting Dale and terminated in the City of London. High arched bridges and a lattice of tracks sliced through the new residential streets. The noise of passing trains and filthy air put off the wealthy middle classes from the freshly built homes. The Potteries & Piggeries slums to the south only made the area less attractive.

Shortly afterwards, the Hammersmith and City Railway began selling cheap working-class tickets, putting suburban living within reach of poorer Londoners. As a result, the new terraces, intended for prosperous families, were quickly sub-divided and let out as single rooms to labourers. Both Bird and Whitchurch filled their remaining plots with cramped three-storey tenement blocks to meet demand. In little time the southern half of Notting Dale became effectively an extension of the neighbouring slums.

Living Conditions in the Avernus

Rooms rented in the lodging houses of Notting Dale were usually furnished with nothing more than a bed, two chairs and a table. In the mixed-sex lodging houses an entire family would often sleep in a single room of this kind.

The fee was about a shilling per night (roughly £2 today), and tenants had to vacate the premises by 10 a.m. the following morning. They were allowed to return only in the evening and, after paying the same amount again, could stay for another night. This meant that the entire following day all family members had to spend their time on the streets, bringing all their possessions with them. Many went to public parks and slept on benches or grass. Others begged or took on casual work.

Migration of the Poor

Meanwhile, construction works in the nearby districts of Kensington and Paddington forced increasing numbers of poor residents out of their homes. This was one of the main reasons behind the intensified migration of Londoners into the Notting Dale area. Furthermore, many factories and businesses employing unskilled labour were removed from the city centre and relocated to the outskirts. Within a short time, this increased movement across the city led to severe overcrowding in the western part of Notting Hill. Separated from the affluent houses to the east by the slums of the Potteries & Piggeries, the area quickly turned into an isolated pocket of extreme poverty.

The Anatomy of Crime and Vice

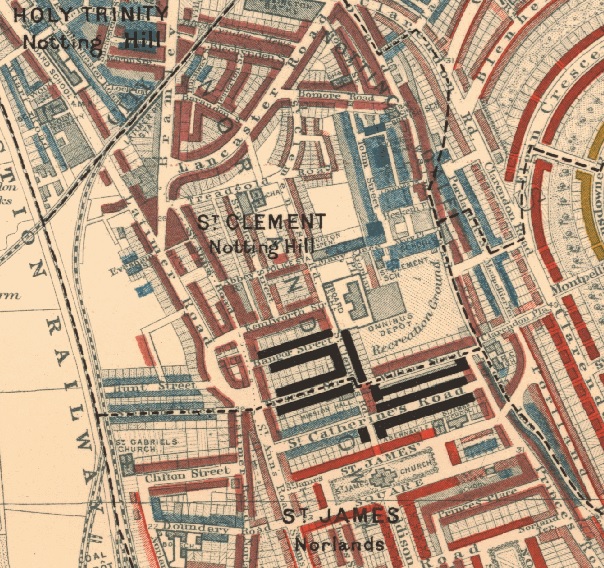

In 1872, the first medical reports were published noting a high mortality rate in Notting Dale. The worst affected was Bangor Street, together with its adjoining side streets: Crescent Street, St Katherine’s Road, Sirdar Road and Kenley Street. The area had a criminal character, its residents drawn from the lowest social classes. It was also known for the dubious morality of its tenants – not to say their outright debauchery. The narrow streets were filled with lodging houses in which almost every window was smashed and stuffed with rags, and in which practically every woman earned her living by practising the world’s oldest profession.

The Labour of Avernus

The census from the last decade of the nineteenth century gives us a deeper insight into the employment patterns of the Avernus community. Working men were most commonly pedlars, pot-washers, street vendors, painters, rag-and-bone men, unskilled labourers, street sweepers and musicians. Women, in addition to prostitution and washing laundry in the nearby wash-houses, also sold flowers, embroidered and sewed. The more skilled inhabitants of Notting Dale included cobblers and plumbers. The best-off tenants were employed in foundries and factories as mechanics. Taxi drivers and horse-breeders appeared only occasionally. The area also abounded in professional thieves, pickpockets and whole swarms of the unemployed.

Laundry Land and Soapsuds Island

Further north, towards what is now Latimer Road, stood vast steam laundries that employed an army of young girls. This part of Notting Dale and its surrounding streets, where laundresses rented rooms in large numbers, became known as Laundry Land and Soapsuds Island.

Women who worked in the large washing and ironing establishments were often the main breadwinners of their families. This was due both to the irregular demand for male labour and to men’s own idleness. Among the urban poor, it became increasingly common for unemployed bachelors to move to the Laundry Land area in search of a wife who could support them. According to a local saying well known to the neighbourhood’s idlers, ‘marrying a laundress was equivalent to possessing a fortune’.

Neglect and Decay

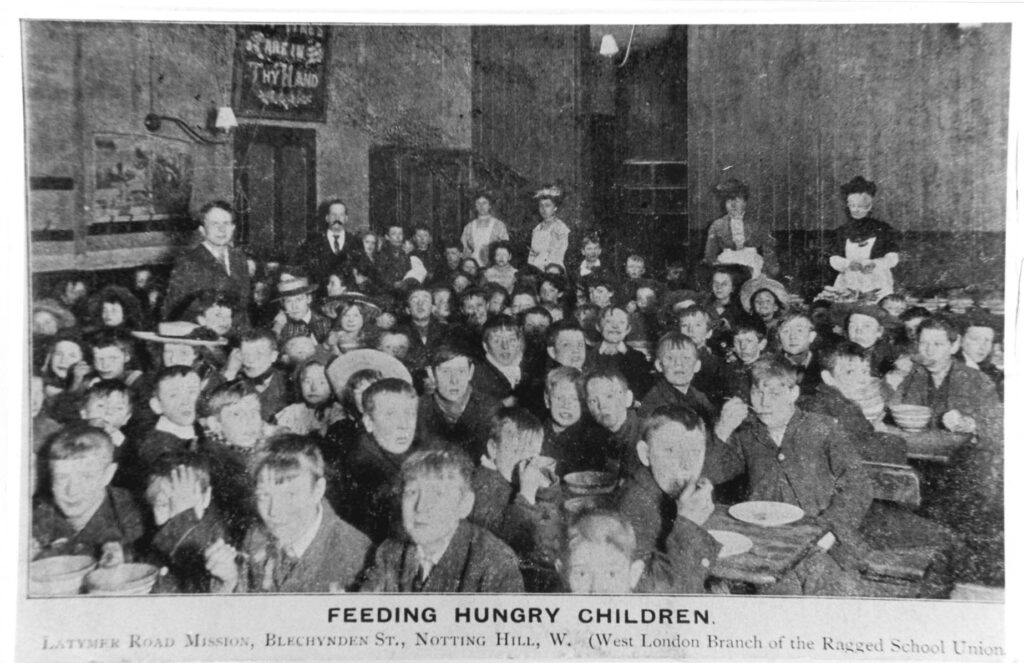

After pigs were removed from the Pottery Lane area in 1878, the local vestry lost interest in the district’s fate. No new legislation was implemented to enforce the rules introduced in 1846, which required the construction of public baths and wash-houses in the city’s poorest neighbourhoods. The 1866 directive regulating the maximum number of people allowed to occupy a single room was also ignored. When, in 1883, the city authorities finally obliged local officials to take action, the number of staff employed within the district sanitary department remained, quite irrationally, unchanged. Despite the efforts of numerous charitable organisations fighting to halt the spread of slums, Notting Dale’s social problems remained unresolved.

A West-End Avernus Exposed

The social conditions of the area became widely known only in 1893, when the Daily News published an article entitled “A West-End Avernus.” The piece drew attention, among other things, to the scandalous living conditions in the Bangor Street. Faced with growing public interest, a series of sanitary inspections was ordered to determine the scale of the problem. In 1895 it was discovered that the mortality rate in Notting Dale was around 42.6 per 1,000 inhabitants. A year later, it was reported that in Avernus 432 out of every 1,000 children died before reaching their first birthday. By comparison, the London average at the time was 161 per 1,000.

Lack of Morality or Mismanagement?

The vestry maintained in its reports that the poor condition of the houses was the result of the residents’ immoral habits and dissolute lifestyles. The main issue, they claimed, was that the community consisted largely of idlers, beggars, vagrants, thieves and prostitutes. Officially, increased supervision of the district was ordered. In reality, however, officials reduced the number of sanitary workers from seven to six. As a result, each inspector became responsible for more than 28,000 residents.

Meanwhile, the population of Avernus was growing at an alarming rate of 4% per year. Many new residents settled here in the hope of securing work on the construction of the Central Tube Railway (today’s Central Line). Between 1897 and 1899 the district’s mortality rate reached a record 53.4 per 1,000.

Faced with such grim statistics, the city authorities launched an inquiry into the state of the district administration. After uncovering numerous failings, the vestry was removed from governance in 1899 and replaced by Kensington Borough Council.

The Resurrection of Notting Dale

This marked the beginning of the slow demolition of Notting Dale’s nineteenth-century housing stock, whose derelict condition made renovation impossible. The old lodging houses were replaced by plain, multi-storey blocks containing thirty-six modern flats, each equipped with a toilet. By 1906, 120 new buildings had also been completed, offering 245 single rooms to rent at very low rates. Even so, the cost proved far too high for the poorest inhabitants of the former slums. Many were forced to relocate elsewhere in London, which helped reduce overcrowding in the Avernus. The new housing and the large-scale inspections imposed by Kensington Borough Council gradually brought improvement. By 1907, the mortality rate had fallen from 50.4 to 30.2 per 1,000.

The total number of new dwellings built in Notting Dale by 1938 reached 1,989. By then, the authorities had also dealt with most of the old, uninhabitable housing. Basement rentals were abolished, and the population reduced by 29%. In 1938, plans were drawn up for the construction of Henry Dickens Court, a project completed in 1953, officially concluding the redevelopment of all streets that had formed Avernus in 1893.

The expansion of social housing in Notting Dale continued regardless. In the 1970s, the towering blocks of the Lancaster West Estate were built. It is here that Grenfell Tower once stood – consumed by fire on 14 June 2017.

Legacy of Avernus

Fortunately, some of Notting Dale’s Victorian terraced houses were successfully restored. Their modest, quiet presence among the mass of grey tower blocks serves as a reminder of the district’s troubled history and helps us understand what shaped its modern appearance. There is no denying that the aftermath of rescuing the inhabitants of Avernus through rapid and inexpensive reconstruction continues to cast a sombre shadow over the area. To this day, Notting Dale remains a distorted reflection of fashionable Notting Hill – as if seen through London’s crooked mirror.

Discover more from London Macabre

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.