Green Park has a very particular atmosphere for a stretch of greenery situated in the very heart of tourist-heavy London. Even on the brightest summer days, one can sense an unusual stillness here – a feeling of suspension and a quiet sadness drifting among the shaded paths lined with twisted, ancient trees. The long, mist-shrouded and at times blood-stained history of this place, combined with urban legends of haunted trees and the duelling ghosts of seventeenth-century gentlemen, undoubtedly lends the park its peculiar charm.

Marshes, Lepers and Forgotten Graves

The earliest references to the land that is now Green Park date back to the Middle Ages. It is believed that for many years these marshy meadows served as a burial ground for lepers from the nearby Hospital of St James, founded by the citizens of London in 1189. In medieval times, leprosy was a common and highly contagious disease. Those who contracted it were sent into isolation in leper hospitals, known as lazar houses.

In time, the surrounding 160 acres of land were also granted to the hospice, and Edward I bestowed the right to hold an annual fair on the neighbouring fields. The area remained waterlogged, frequently flooded by the River Tyburn, while pigs were raised on the surrounding meadows.

When the Dead Made Room for Deer

The old hospital was closed as a result of the Reformation. Henry VIII wished to create an extensive hunting ground to the west of his palace at Whitehall, and so in 1531 the former hospital lands were surrendered to the Crown. From the areas that would later become St James’s Park, Green Park, Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens, a vast deer park was formed. The leper hospital was erased from the landscape, and its many unfortunate dead were consigned to oblivion, buried beneath a thick layer of parkland soil.

Royal Entertainments Rarely End Well

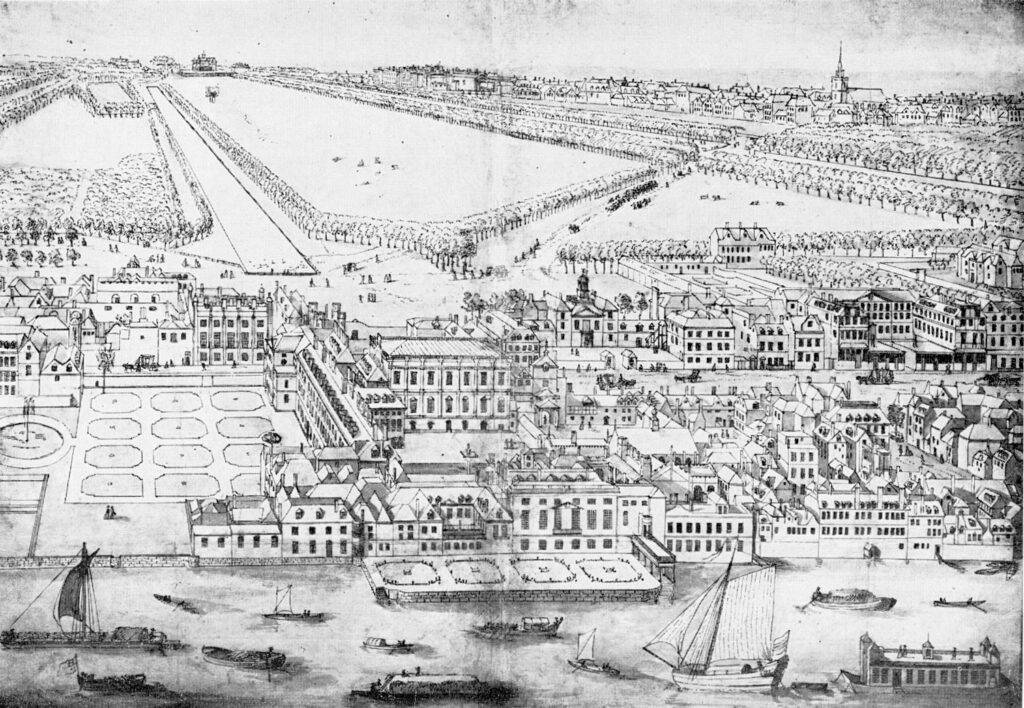

In 1668, Charles II wished to be able to walk on foot from Hyde Park to St James’s Park without ever leaving royal grounds. He therefore purchased the remaining strip of land between the two existing parks, enclosed it with a brick wall, and gave Green Park its first official name: Upper St James’s Park.

The king soon fell in love with his new green retreat, entertaining guests with royal firework displays and popular fairs that became a tradition long continued after his death. The festivities, however, were not always a resounding success and at times spiralled out of control.

On 27 April 1749, a huge firework display was held in Green Park to celebrate the end of the War of the Austrian Succession. George II commissioned Handel’s Music for the Royal Fireworks to accompany the display. An enormous pavilion, known as the Temple of Peace, was built in the park for the event and exploded during the display, when 10,000 fireworks ignited within minutes. Three people were killed in the blast.

A Dubious Place After Dark

Despite the fairs and its proximity to the royal residence, for much of the eighteenth century large parts of Green Park remained unlit and semi-rural in character – ideal conditions for highwaymen, robbers and rapists to operate. Even the writer Horace Walpole was not spared, falling victim to an attack by the notorious highwayman James MacLaine there. The park was also known as a popular duelling ground, and visiting it after sunset or in the early hours of the morning was widely regarded as an exceptionally unwise activity.

A Matter of Honour

On the morning of 11 January 1696, Member of Parliament Sir Henry Colt and the quarrelsome libertine Robert “Beau” Fielding met at the rear of Cleveland House (now Bridgewater House), on the eastern edge of Green Park, to settle their differences at dawn. The immediate catalyst had been a physical confrontation at the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane the previous evening. Fielding, well known for his vanity and explosive temper, had taken offence at Sir Henry and issued a challenge for the following morning.

Both men were competing for the affections of Barbara Palmer, the first Duchess of Cleveland – a former mistress of King Charles II and one of the most notorious figures in London society. Fielding deliberately chose the duel’s location behind Cleveland House, as the duchess’s windows overlooked Green Park, thus affording her a perfect view of the encounter and a display of his supposed bravery.

Fielding, however, whose honour and courage were not among his most admirable qualities, struck Sir Henry dishonourably before he could even draw his sword. Despite his wound, the baronet managed to disarm his opponent, and the fight ended unfavourably for Beau. According to legend, to this day – on the anniversary of the duel – the misty air of Green Park resonates with the sounds of combat and the laboured breathing of the fighters for several minutes just before sunrise.

What Did Not Happen at Sunrise

There was no doubt that on Sunday, 11 January 2026, I would find myself at half past seven in the morning in the narrow stretch of Cleveland Row, beside the gardens of Bridgewater House – frozen to the bone, clutching a cup of steaming, rapidly cooling coffee in an icy hand, impatiently awaiting sunrise at precisely 8:03 a.m.

Unfortunately, despite straining my ears and standing utterly still in the deserted park until half past eight, absolutely nothing happened. No sounds of battle, no steaming breaths, no clash of crossing blades. To be certain, I nervously glanced around and spoke the duellists’ names aloud, but this failed to interest anyone except a solitary squirrel. Undeterred, I turned my attention elsewhere, determined to uncover another of Green Park’s many hidden mysteries.

The Tree Everyone Fears… but Can’t Find

Among the park’s trees stands a single specimen with a particularly unsavoury reputation. People never sit in its shade, and squirrels and birds give its branches a wide berth. From its trunk, inexplicable sounds are said to emerge. Some claim it is the rough voice of a man engaged in animated conversation, which falls silent the moment anyone begins listening too intently. Others are convinced that a sinister giggle can be heard nearby, piercing listeners with icy fear. Still others report a strange, mournful moaning – the sound of someone sunk in utter despair or in the throes of death.

The tree is said to radiate an almost irresistible sadness and despair which, according to legend, draws suicides to it. It is hardly surprising that it is also known as the Tree of Death, as several people are said to have chosen to end their lives in this very spot. Among the stories are those of a man who poisoned himself while sitting in its shade, and of a violinist who fell into hysteria after inexplicably losing his instrument beneath the tree’s branches. Visitors to the park occasionally report seeing a figure dressed in black standing very close to the trunk. The apparition vanishes the moment the observer looks in its direction a second time.

A Legend Without a Location

The problem is that no one knows for certain which tree in Green Park is that tree. There are several contenders, but no consensus. Despite the many stories circulating through the city, the location of the Tree of Death remains a mystery. Park staff and paranormal investigators alike have been unable to identify it conclusively, and as a result it now exists more as an urban legend than as a single, agreed-upon tree. Having circled the park twice, I rebelliously picked my own favourite contenders, fully aware that this private act of classification was as inconclusive as every attempt before it.

After all, Green Park did not surrender its secrets to me. The tree remained anonymous, the ghosts declined to reveal themselves at dawn, and the park – as befits a place with such a long history – kept its mysteries to itself. Perhaps its true appeal lies in this: one can wander through it, seemingly calm and pleasant, unaware of the stories buried beneath its surface. In truth, it is a park that refuses to feel cheerful – and seems rather proud of the fact.

Discover more from London Macabre

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.