Notting Hill is a typical example of a London district that has undergone a complete transformation in just two centuries. Today, it is one of the city’s most popular tourist destinations – the heart of the world-famous carnival and home to the vibrant antique market stretching along the picturesque Portobello Road. Yet the Notting Hill of old was far removed from the pastel façades and bright pink peonies adorning today’s window boxes.

In the 1820s, its residents – alongside brickmakers and stove builders – were mostly pigs. The area surrounding Pottery Lane was a breeding ground for disease and crime to such a degree that by the late nineteenth century the north-western part of Notting Hill was known as Avernus (Latin: ‘descent into hell’). Racial street wars, mass immigration of impoverished Caribbean communities and severe overcrowding in rented tenements were only some of the problems the residents faced well into the second half of the twentieth century.

The Story of Pottery Lane

The troubled beginnings of Notting Hill are recalled today by Pottery Lane, located in the heart of the district. Wandering along this narrow, charming street, it’s hard to imagine that less than two centuries ago, one stood in what was once among the most dangerous places on the outskirts of London.

Known to locals at the time as Cut-throat Lane, this unassuming path led deep into the slums known to Londoners as The Potteries and Piggeries.

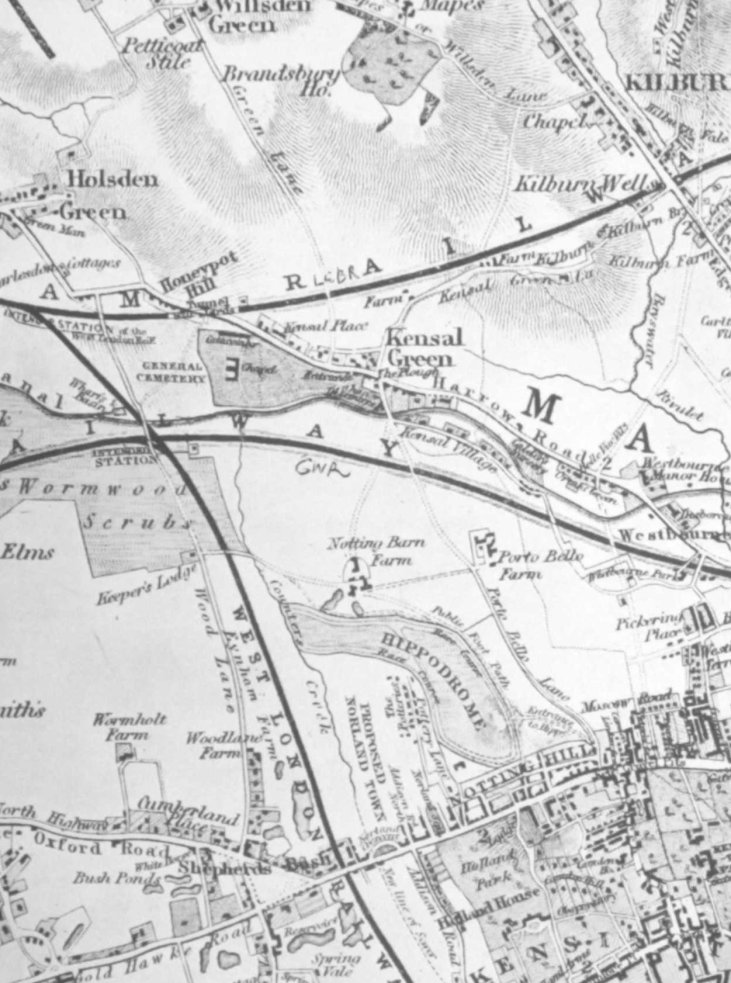

Pig breeders began arriving around Pottery Lane at the start of the nineteenth century, when rapid building works spread across what is now Paddington and Marble Arch. Displaced farmers, forced to abandon their land, sought a new and remote location suitable for their trade. At the same time, the western reaches of Notting Hill were already used for clay extraction – a resource essential to the production of bricks and ceramic tiles, and highly coveted in the age of London’s rapid growth.

The second largest group to settle in the area were potters and stove-makers. Bricks were fired in large, free-standing kilns built near the pits. Only one of these kilns survives to this day, standing on the eastern side of Walmer Road. Converted into a private home a few years ago, it is now available to rent for £1,100 per week.

Living Conditions on Pottery Lane

Brick kilns, pottery furnaces and pigsties crowded together on a small patch of land – without drainage or sewage – created a truly explosive mix. By 1838, the Commission for Urban Poverty had already drawn attention to the scandalous state of the housing in the area.

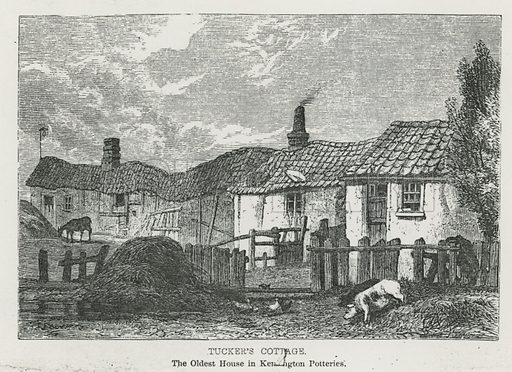

Most dwellings were built on stagnant pools that had formed in the clay pits. In some cases, the floors had completely given way. It was not uncommon for one corner of a room to be flooded with stagnant water, while in the other stood a bed or straw mat where the entire family slept.

The lack of any building supervision encouraged squatting and makeshift settlements. Many huts and shacks – built by hand from scavenged materials – were in fact one-room sties, where farmers often shared a roof with their livestock.

The Stench of the Potteries

Further insight into life in the Potteries and Piggeries comes from the reports of the Metropolitan Sewers Commission, established in 1847 when London authorities, threatened by cholera, decided to investigate the area’s sanitary conditions.

According to one report, the population of Pottery Lane reached 1,056 people, while the number of pigs exceeded 3,000 – on a street barely 300 metres long. Between 1846 and 1848, conditions were so appalling that the average age at death was just 11 years and 7 months, compared with the London-wide average of 37.

The main cause of this horrifying mortality rate lay in the pits that covered the land. Dug deliberately by the pig breeders, they were used to store slurry and animal waste. Many were located directly beside homes, with bedroom windows looking out – or rather down – onto the cesspools below.

Preparing and distributing animal feed was another popular occupation. The mixture was made from sheep entrails, blood, and various organic refuse, often in an advanced state of decay. Collected from elegant West End hotels and local slaughterhouses, the waste was boiled down in huge copper vats. The stench – nauseating and ever-present – drifted across the entire district.

The problem was made worse by unpaved roads choked with filth, and wells contaminated with waste. The nearby brickworks deepened the landscape with even more pits, which filled with foul, stagnant sludge – a mixture of rainwater, offal, dung and sewage. One such pond was so vast that locals called it The Ocean. It was finally filled in during the 1860s as part of an improvement scheme, and by 1892 the site had been transformed into today’s Avondale Park.

The Fall and Rise of Notting Hill

The cholera outbreak of 1849 plunged the area into even deeper crisis. Within the first month, 21 deaths were recorded around Pottery Lane. Another 29 followed, claimed by typhus and other diseases linked to the vile living conditions. Before long, the mortality rate in the Potteries and Piggeries reached a shocking 60 per 1,000 inhabitants – compared to London’s average of 25. Poverty, depravity and filth became notorious across the district.

Most pig farmers were taken to court for violating sanitary regulations. The court ordered them to remove their livestock immediately, prompting desperate appeals to the local magistrates. As a result, the verdicts were never fully enforced. Although by 1856 the number of pigs had been halved, mortality rates remained unchanged. A second cholera outbreak in 1854 claimed another 25 lives, and by 1856, 87% of all recorded deaths in the district were among children under five.

The real breakthrough came only in the early 1860s, when the city authorities began draining the land and installing proper sewage systems. Streets were paved, The Ocean was buried, and by 1878, large-scale pig farming had disappeared. Over time, the squalid slums quietly transformed into part of the charming, affluent Notting Hill we know and love today.

Discover more from London Macabre

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.