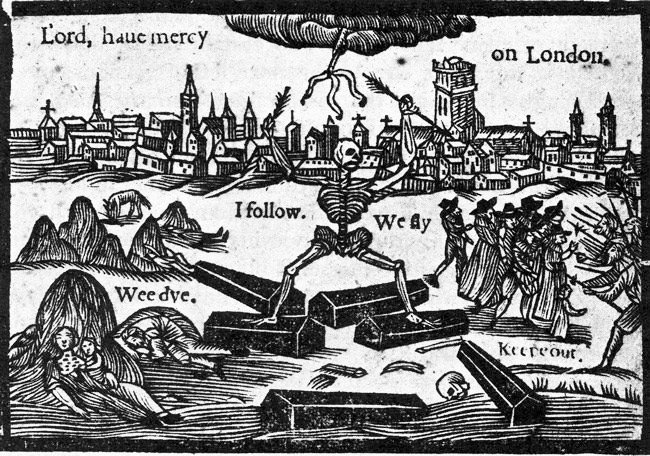

The Great Plague of 1665 was preceded by unsettling portents that lent it a mysterious, almost otherworldly character. In December 1664, a comet appeared in the night sky, deemed profoundly ominous by scholars and astrologers alike. The conjunction of Mars and Saturn in November was interpreted as a harbinger of war, pestilence, and famine. The appearance of yet another comet in March only deepened public anxiety. Even the most esteemed astrologers were unable to explain the phenomenon.

Meanwhile, the plague ravaging France and the Netherlands further sharpened fears among the population. The Church regarded the epidemic as divine punishment for human sin and called for fasting and fervent prayer in the hope of deliverance. Superstitious Londoners increasingly recalled the prophecy of Edlin, who had foretold a great plague descending upon London in the year 1665.

An Old Enemy

Plague, however, was nothing new to Londoners of the time. The Black Death had first reached Europe in 1346 and had returned to the capital at regular intervals ever since. As a result, the first fatal cases recorded in the parish of St Giles-in-the-Fields in late December 1664 not only failed to alarm those in power, but passed almost entirely unnoticed.

By the seventeenth century, plague had become endemic in England. It is therefore mistaken to believe that the epidemic of 1665 began when a Dutch ship carrying bales of flea-infested wool entered a Thames-side port. The long-held conviction that Mary Ramsay brought the plague from France – on the grounds that she was the first recorded death from plague in the parish of St Olave – is equally difficult to substantiate. Human nature has a tendency to seek scapegoats, particularly when blame can be placed on an outsider.

The reality is that from 1603 onwards, when 33,347 people died of plague in London, the city recorded only four years entirely free from the disease. Another outbreak had struck in 1647, a mere twenty-eight years earlier, meaning that most adult inhabitants remembered its previous visitation all too well.

A Crowded Capital

Only a few years before the epidemic, England had entered the period of the Restoration, with Charles II returning to the throne in 1660. His father, Charles I Stuart, remains the only monarch in the nation’s history to have been overthrown by his own subjects and executed, in 1649. Following the collapse of the English Republic under Oliver Cromwell, the royal family and numerous courtiers returned from exile abroad. The city swarmed with travellers and migrants seeking fortune and opportunity. This influx of people was one of the indirect reasons why the Great Plague of 1665 proved so devastating. The population of the capital had grown to nearly half a million souls.

A City Unprepared

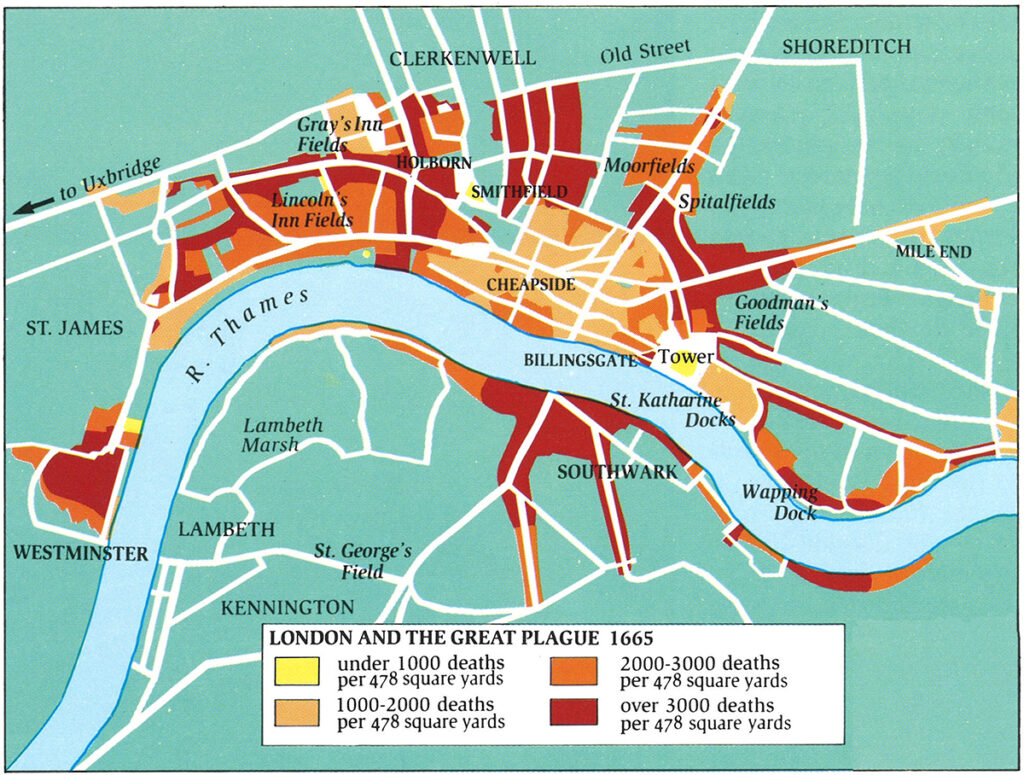

Seventeenth-century London was utterly unprepared for the brutal assault of the plague. The overcrowded and filthy city, built from tightly packed wooden houses, expanded at an alarming rate beyond its medieval walls. The urban poor numbering some 250,000 lived on the fringes of the metropolis, in the wretched huts of Westminster, Holborn, and Southwark, amid repellent accumulations of waste and open gutters running down the streets.

Even the most basic standards of hygiene were impossible to maintain. The absence of sewers, limited access to clean water, and open cesspits created a paradise for swarms of flies. The slippery streets were coated with horse dung, animal waste, and rotting refuse. Residents of the upper floors habitually emptied kitchen slops and the contents of chamber pots directly out of their windows.

Stench Within the Walls

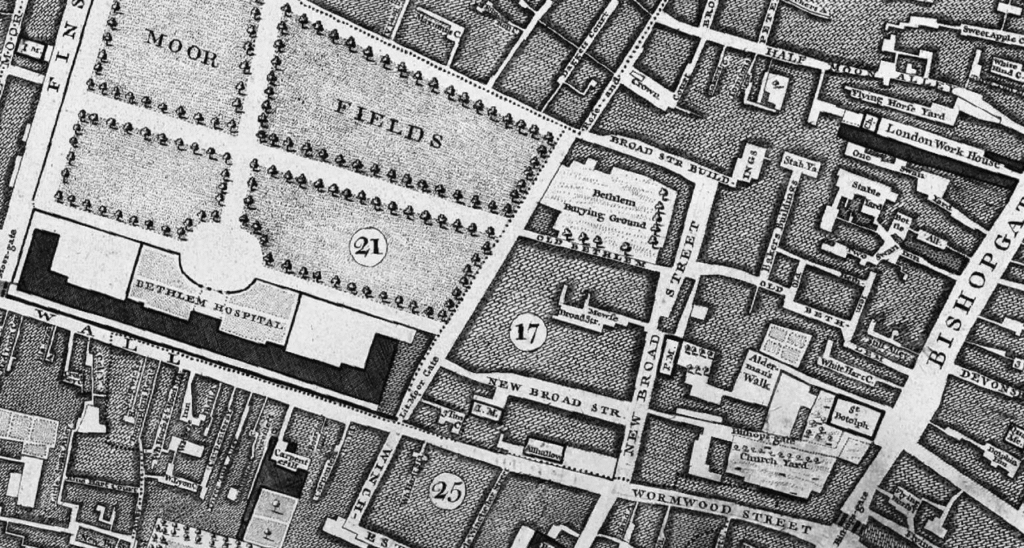

Conditions within the city walls were little better. The City authorities employed street cleaners who roughly cleared the roads and carted away the worst filth to the outskirts of the metropolis, yet the stench that hung over the capital was unbearable. Those forced to venture outdoors walked with handkerchiefs or small posies of flowers pressed to their noses. Wealthier inhabitants travelled by carriage, avoiding the narrow and foul-smelling alleys. The City of London lay between the polluted River Fleet and the foggy marshlands of Moorfields to the north. Water drawn from the city wells first passed through overcrowded burial grounds.

A Pestilent Metropolis

Cramped and dim dwellings at street level and in cellars lay buried in the shadow of upper storeys, which were extended so aggressively that neighbours on opposite sides of the street could shake hands through their windows. On rainy days, the lanes were submerged in foul-smelling mud reaching ankle height, with torrents of filthy water rushing through the city gutters. The entire metropolis lay beneath heavy clouds of black smoke from more than fifteen thousand coal-heated homes, as well as numerous soap works, iron foundries, and breweries. Lice, bedbugs, fleas, parasitic worms, and rats were an inescapable part of urban existence, while roaming packs of stray dogs and cats completed the grim portrait of the capital.

Naming the Plague

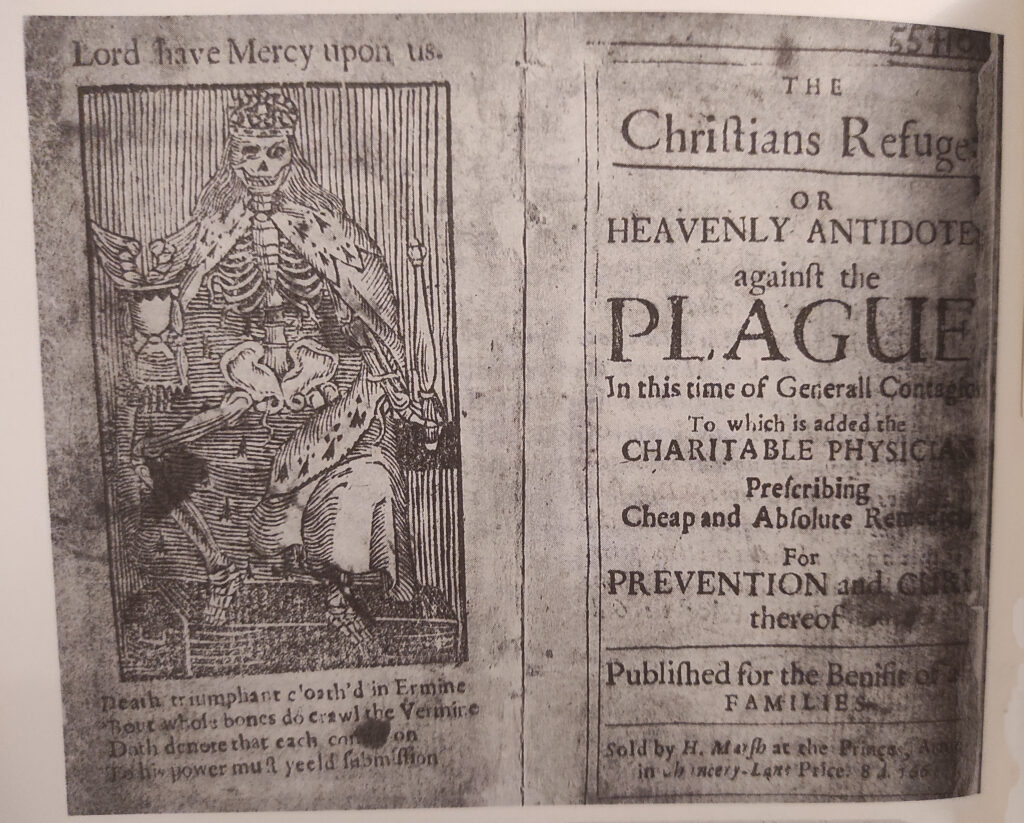

The term Black Death is a relatively modern one. In 1665, Londoners most commonly referred to the plague as the Great Mortality or the Great Pestilence, while contemporary writers favoured the expression the Great Death. The phrase Black Death first appeared in sixteenth-century Swedish and Danish chronicles. Contrary to popular belief, it does not seem to have referred to the extensive necrotic and gangrenous changes to patients’ skin, which could turn black or purplish in colour, but rather to blackness as a symbol of fear, mourning, and despair – intended to emphasise the terror and mystery of the disease.

In Britain, the term came into use only towards the end of the seventeenth century, applied retrospectively to the epidemic of 1346 in order to distinguish it from the Great Plague that struck London in 1665. Whatever the true origin of the name Black Death, it has endured to the present day, inspiring artists to portray the epidemic as a dark rider on horseback, mercilessly cutting down his victims with a scythe – an image that remains synonymous with death to this day.

Agents of Contagion

In 1894, Alexandre Yersin discovered that plague was caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, transmitted primarily by infected fleas feeding on black rats. These parasites were capable of surviving for more than six months within bales of wool without a host. Modern researchers also believe that human lice – ubiquitous among London’s poorer classes – may have played a significant role as vectors. The Great Plague of 1665 was conclusively identified as an outbreak of plague in 2016, following DNA analysis of teeth recovered from victims buried beneath the present-day Liverpool Street Underground station.

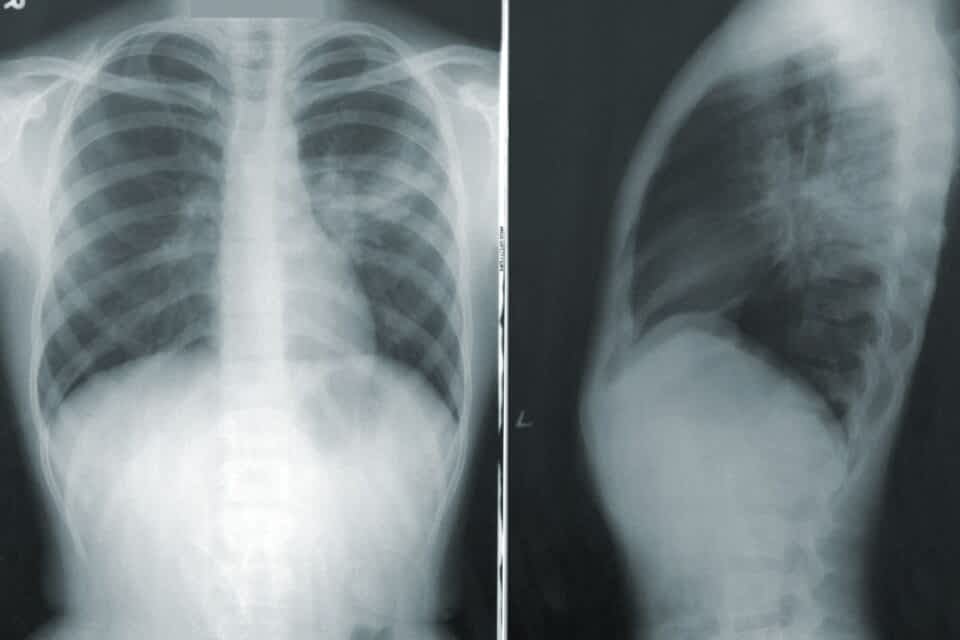

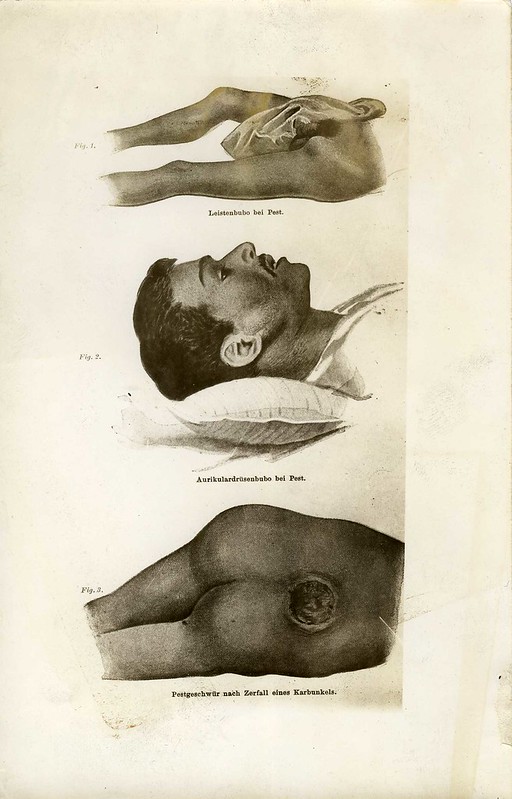

Bubonic Plague – The Swollen Death

The most common form of the disease was bubonic plague, spread by the parasites already described. Within hours of a bite, the infection manifested as high fever, chills, uncontrollable vomiting, severe headaches, and profound weakening of the body. Within a dozen hours, the lymph nodes – most often in the groin or under the arms – began to swell into painful lumps known as buboes. These growths were intensely tender, soft to the touch, and could reach the size of an apple. As the disease progressed, black or dark blue patches of gangrene appeared near the sores, most commonly on the thigh or upper arm.

In the final stage of the illness, around the fifth day after infection, the swellings often burst, releasing dark pus and unbearable stench. A common practice among the physicians was to lance the buboes in the hope that draining the infected blood might improve the patient’s condition. In reality, cutting open and emptying these growths without any form of anaesthesia or antiseptics resulted in excruciating end in the vast majority of cases. The last symptom – small red spots surrounded by bluish or black rings, known as tokens – often appeared on the chest or back, usually signalling death within a matter of hours.

Pneumonic Plague – The Airborne Curse

The second form of the disease was pneumonic plague, still regarded today as one of the most contagious and severe infections known to humanity. It spread through airborne droplets when plague bacteria entered the respiratory tract, triggering inflammation of the mucous membranes and gradually invading the lungs along the lymphatic and blood vessels.

The prognosis for this form of plague was rather grim. Respiratory failure and circulatory collapse were common, frequently ending in death. Fever and headaches appeared within hours of infection, followed by rapidly worsening symptoms resembling severe pneumonia: shortness of breath, coughing, chest pain, and coughing up blood. Untreated pneumonic plague could kill within as little as three days.

Septicaemic Plague – Bloodborne Doom

The final recognised form was septicaemic plague, which proved exceptionally violent and utterly incomprehensible to physicians of the time. In this variant, plague bacteria entered the bloodstream directly, reaching the organs within hours. Historical sources describe numerous cases of individuals who went to bed in perfect health only to be found dead the following morning. This course of illness inspired particular terror among witnesses, as it bore little resemblance to other forms of plague and progressed at a speed that seemed explicable only as immediate divine punishment. Among the few patients who survived for several days, the most common symptom was a dark purple or black discolouration of the hands and feet, caused by circulatory failure and advancing gangrene.

Fear Without Understanding

In the seventeenth century, the plague was a disease shrouded in mystery and universal terror. Many believed it rose from the depths of the earth itself, accidentally released during volcanic eruptions. A cloud of noxious vapour was thought to drift over human settlements, infecting all who lay beneath it. Others sought explanations in strange weather, aberrant animal behaviour, and the sudden explosion in local populations of moles, frogs, mice, and flies.

Medical knowledge of the period was equally limited, often rooted in superstition and folk medicine. Alongside the plague, Londoners suffered from numerous other illnesses, including smallpox and tuberculosis, whose early symptoms closely resembled those of the pestilence and made accurate diagnosis difficult. Although years entirely free of plague were rare in London, many practising physicians had never encountered a confirmed case in person.

The Medical Collapse

During the years of Cromwell’s Republic, the rules governing medical practice were relaxed. Many practitioners in London had received no university training, and apothecaries were frequently regarded as physicians. The distinction between qualified, experienced doctors and healers, quacks, and charlatans was dangerously blurred. At the onset of the epidemic, around 80 per cent of Fellows of the College of Physicians, along with numerous apothecaries and surgeons, fled the city. Of more than six hundred medical practitioners in London, only about two hundred and fifty remained – most of them unlicensed and lacking the knowledge required to prevent their patients’ deaths.

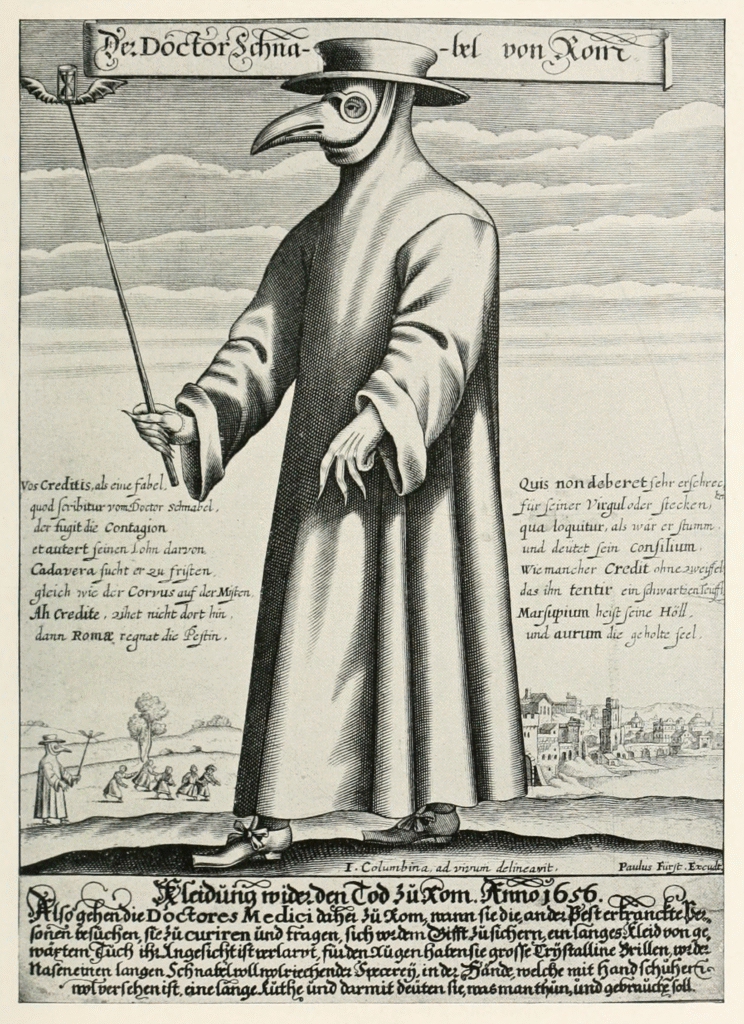

The Plague Doctor

Those physicians who stayed adopted a distinctive costume, designed by a French doctor and widely used across Europe. According to contemporary belief, plague was transmitted by miasma – a poisonous stench hanging in the air. For this reason, doctors wore masks with long beak-like protrusions stuffed with fragrant herbs and flowers. The rest of the outfit offered some protection against infected fleas. Floor-length coats, gloves, hoods, and hats were made from thick cloth or leather, waxed and oiled to allow for easier cleaning and disinfection before returning home.

Physicians also carried long staffs, which served as symbols of their profession. These allowed them to examine patients without touching clothing or bedding and to keep infected passers-by at a distance. The staffs were also used as gags during painful procedures carried out without any form of anaesthesia.

Popular Remedies & Rituals

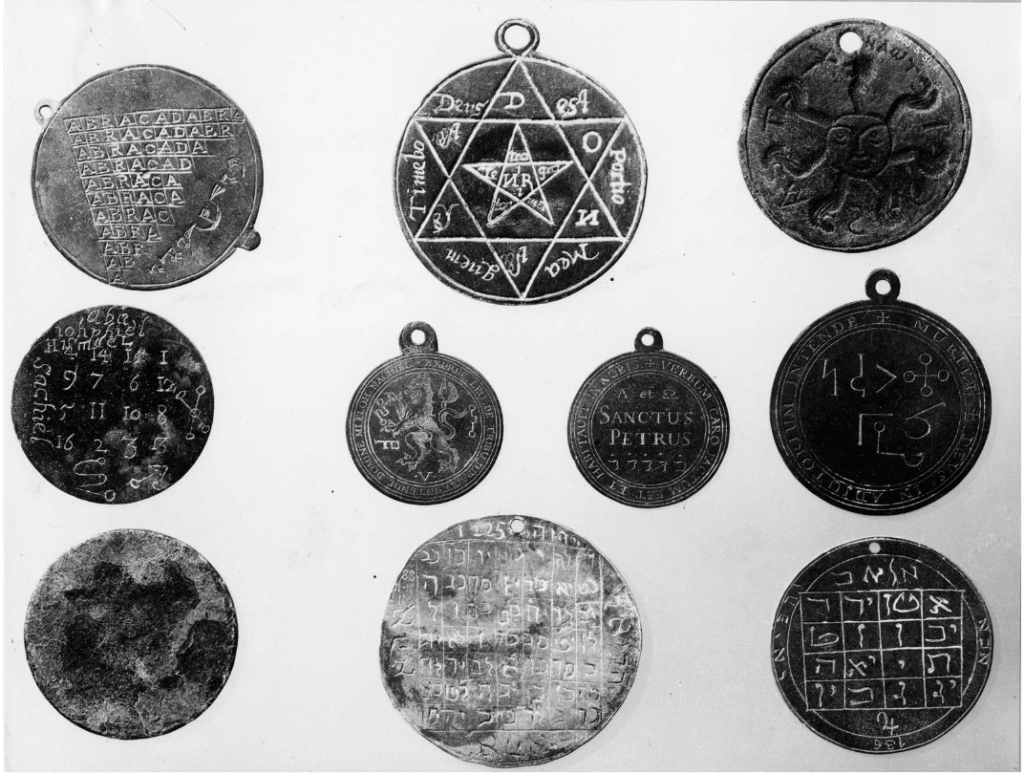

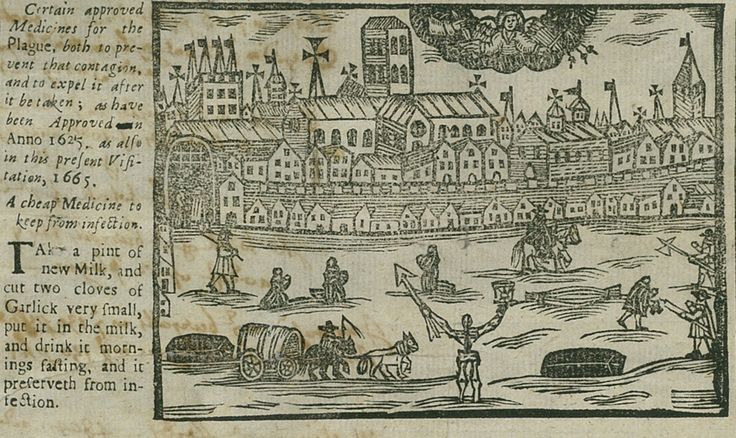

Medical treatments of the time were based largely on herbal lore, folk superstition, and even elements of alchemy. Although none of these methods had any real effect on the course of the disease, they at least offered the desperate population an illusion of hope. One of the most popular preventive measures was carrying small bouquets of flowers held close to the nose, believed to block the harmful miasma drifting through the air.

Those employed to dig mass graves rarely parted with tobacco, convinced that smoking disinfected the airways. Even children were encouraged to take up the habit. Other disinfectants included vinegar, widely used to cleanse coins at London markets. To avoid direct contact, customers dropped payment into buckets of vinegar prepared by the seller.

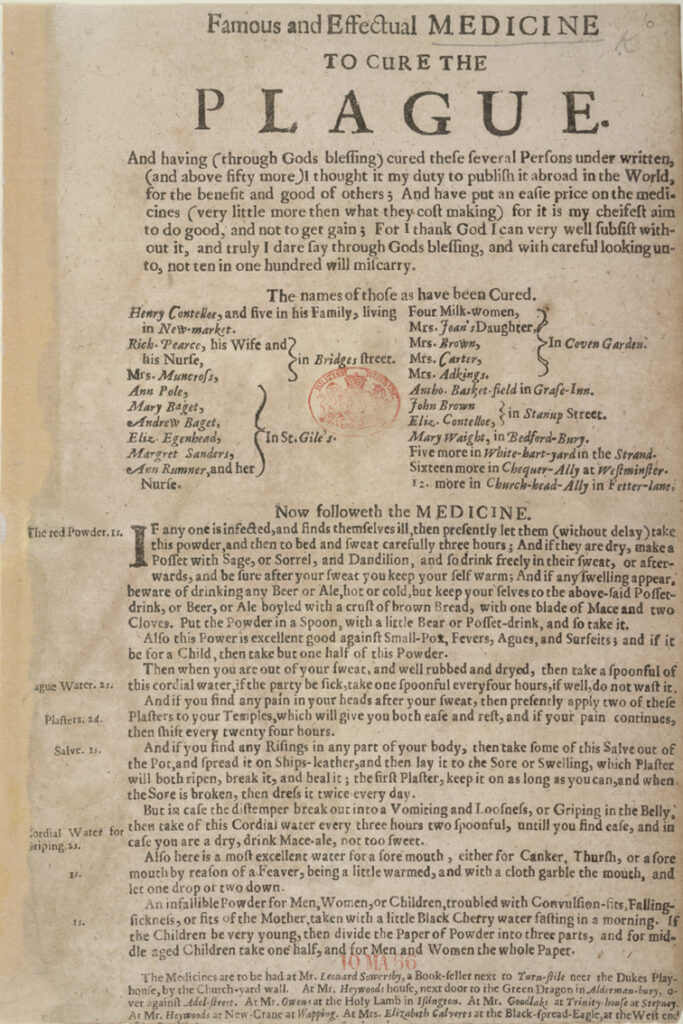

Merchants of False Hope

Healers treated their patients with a range of methods that were often absurd. These included powders made from unicorn horn, applying leeches to the arms or legs, and tying a live, plucked chicken to the buboes, leaving it there until it died. Healers also wore various talismans intended to ward off the plague: scraps of paper inscribed with the word abracadabra arranged in a triangle, lucky rabbit’s feet, and dried toads.

The flight of qualified physicians created fertile ground for fraudsters and opportunists seeking quick profit. Around St Paul’s Cathedral, numerous shops sold miraculous elixirs, pills, and plasters that supposedly protected against the plague. Popular remedies included pills containing hellebore and opium to induce excessive sweating, and purgative tablets intended to expel the plague germs from the body. In reality, such treatments often hastened death. One particularly audacious quack spread the rumour that infection with a venereal disease rendered a person instantly immune to the plague.

Public Regulations

As the epidemic advanced, the College of Physicians issued a series of preventive guidelines for the capital’s inhabitants. Travel without a certificate of health was banned, as were social gatherings. Public venues such as theatres, fairs, dance halls, and most taverns and alehouses in affected districts were closed.

Parishes were tasked with providing financial relief to the poor, alongside organising weekly prayers and fasts to appease God. Beggars and the homeless were forbidden from wandering the streets, the sale of spoiled food at markets was restricted, and residents were instructed to maintain absolute cleanliness in their homes and streets.

The Lord Mayor ordered daily sweeping and washing of pavements, but as the number of cases rose, these measures became increasingly difficult to enforce. After weeks of quarantine in many households, the condition of the streets deteriorated to levels worse than before the epidemic. Slaughterhouses were moved to the outskirts of the city, as were burial grounds for plague victims.

Smoke, Vinegar and Fire

The College of Physicians supplied significant quantities of medicines, distributed by an apothecary at Amen Corner. Orders were also issued for the fumigation of homes, especially rooms occupied by the sick. Strong-smelling substances with supposed disinfectant properties were burned – most commonly mixtures of sulphur, tar, saltpetre, and powdered amber. Those unable to afford such materials burned old shoes, scraps of leather, and horn in their hearths to achieve a similar effect.

Windows were kept tightly shut, and some even stuffed keyholes with rags. Household fires and fireplaces were kept alight even during the hottest days, regularly sprinkled with disinfectant mixtures that filled the sickroom with thick, acrid smoke. Reports of the effectiveness of fumigation likely stemmed from the fact that the fumes drove rats elsewhere. Physicians also recommended inhaling vinegar vapours and often sucked on pieces of pure gold during visits to patients.

Spring Unleashes Death

The bitter, unforgiving winter that had kept the epidemic at bay loosened its grip on London in early March 1665. Almost at once, the plague began to reap a grim harvest among the poor of St Giles-in-the-Fields. A dry, unusually warm spring followed, accompanied by vast swarms of flies so dense they coated walls, furniture, and bedding alike – an ominous portent of what was to come.

Two suspicious deaths in December 1664 and another in February 1665, none officially recorded as plague cases in parish reports, were quietly ignored by the authorities. By the end of April, only four victims of the disease had been acknowledged across the city, yet overall mortality had risen sharply from 290 to 398 deaths – a clear indication that infections were being deliberately concealed for fear of compulsory household quarantine.

The Plague Spreads

By the first half of May, the plague had already escaped St Giles-in-the-Fields and reached the parish of St Clement Danes, where four deaths were recorded. By the end of the month it had spread steadily through Westminster, Holborn, Whitechapel and Cripplegate, advancing along Chancery Lane, the Strand and Fleet Street. At last it breached the walls of the City of London itself, claiming a life in the parish of St Mary Woolchurch, on the site of today’s Mansion House. In the final week of May, parish bills recorded seventeen plague deaths within the city.

The close of a hot, parched June brought more than one hundred deaths in St Giles-in-the-Fields alone. Only then did the authorities order the isolation of the district. Guards patrolling the parish streets were instructed to detain anyone attempting to leave the quarantined area. Had such measures been taken three months earlier, the plague might never have claimed one hundred thousand Londoners. By June, however, it was already far too late.

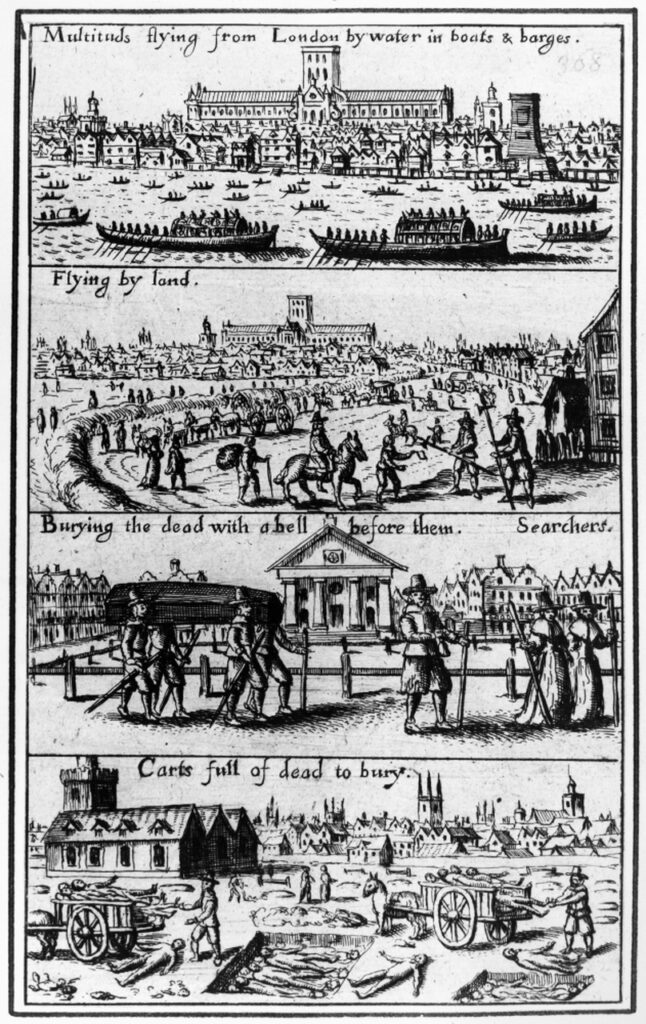

The Great Flight

May also marked the beginning of a great exodus of the city’s wealthy. Those with means gathered their portable possessions, dismissed most of their servants, bolted their doors, and fled to country estates. The earliest fugitives were met with scorn and cynical comments from fellow aristocrats, yet within a month those same critics were hastily arranging their own escape.

Lawyers and barristers of the Inns of Court shut their chambers and abandoned London en masse. Affluent physicians followed suit, awkwardly justifying their departure by claiming that wealthy patients required their care in the countryside. Only a shamefully small number of trained doctors chose to remain behind to treat the poor.

Clergymen deserted their congregations and vanished from the city within the same month. The governor of Newgate Prison and the Lord Chief Justice suspended all sentences and left the capital as the disease tore through the prison population. From June until the end of 1665, the city records contain no mention of a single execution.

Capital Without the King

On 7 July, news spread that King Charles II had fled London with his court and taken refuge in Isleworth. What remained of the aristocracy, along with wealthy merchants and much of the middle class, followed swiftly in his wake. In the emptied City of London remained only the resolute Lord Mayor, a diminished City Council, and a populace of poor already decimated by disease. The districts beyond the city walls were left in the hands of a handful of officials whom the king had expressly forbidden to leave. The selfish conduct of the monarch and his court during the epidemic remains one of the darkest stains on the reputation of Charles II.

The Poor Flee

Terrified by the advancing plague, the city’s poor also attempted to flee – but for them, escape often proved fatal. Lacking transport, sufficient food and water, or a secure destination, impoverished families were forced into days of wandering towards nearby villages. As infection rates in London climbed, rural communities grew increasingly hostile to travellers and frequently denied them entry, even when health certificates were presented.

Unable to enter any town, the refugees were driven back towards London across fields and pastures, surviving on whatever they could beg or steal. Many perished from hunger and dehydration before reaching the city gates again. Fearing for their own safety, local inhabitants often left the bodies of strangers where they fell, abandoned to birds and wild animals.

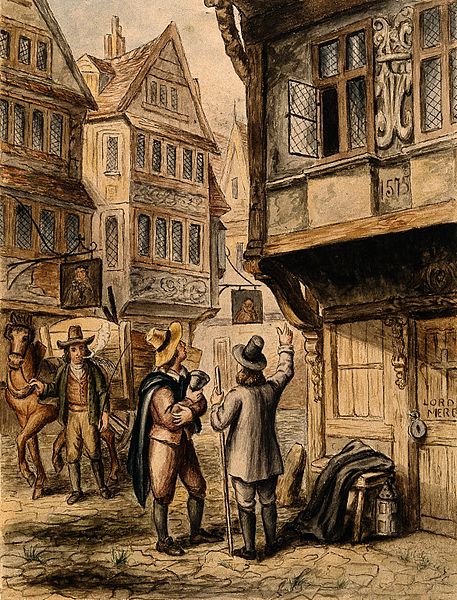

Marked for Death

One of the earliest measures imposed by the authorities was the locking of houses in which infection had appeared – a practice known in London since at least 1518. If a single member of a household fell ill with the plague, the entire house was sealed at once, even if no one else showed symptoms. This ignorance, and the forced confinement of the healthy with the infected, contributed directly to the appalling mortality rates and encouraged families to conceal the true cause of death.

A red cross was painted on the door of the house, accompanied by the words “Lord have mercy upon us”, warning passers-by of the danger within. A watchman was stationed outside to ensure that no friends or neighbours attempted to communicate with the family. Parish records from 1665 frequently list several individuals bearing the same surname who died within days of one another – grim evidence of how swiftly the plague consumed households condemned to quarantine. The merciless confinement lasted forty days, during which the only person permitted to enter the house was a nurse employed by the parish.

Guardians and Thieves

Trapped families were entirely at the mercy of the watchman, who was responsible for supplying food, water, medicines, and messages to the outside world, as well as warning passers-by to keep their distance. It was a job few were willing to take. Overburdened by the costs of the epidemic, parishes offered the lowest possible wages to both guards and nurses. As a result, these roles were rarely filled by honest individuals, and more often by drunkards, petty criminals, and the desperate unemployed.

Nurses of Misery

The nurses themselves were usually illiterate, elderly women living in extreme poverty, with no understanding of medicine. Their task was to tend to the sick within sealed houses, yet neither their character nor their background was ever examined by the parish. Many of them, instead of providing care, robbed families who had no legal right to refuse them entry. Lured by the prospect of plunder, some were said to suffocate the dying on their beds or deliberately infect healthy children using pus taken from the ruptured buboes of deceased parents.

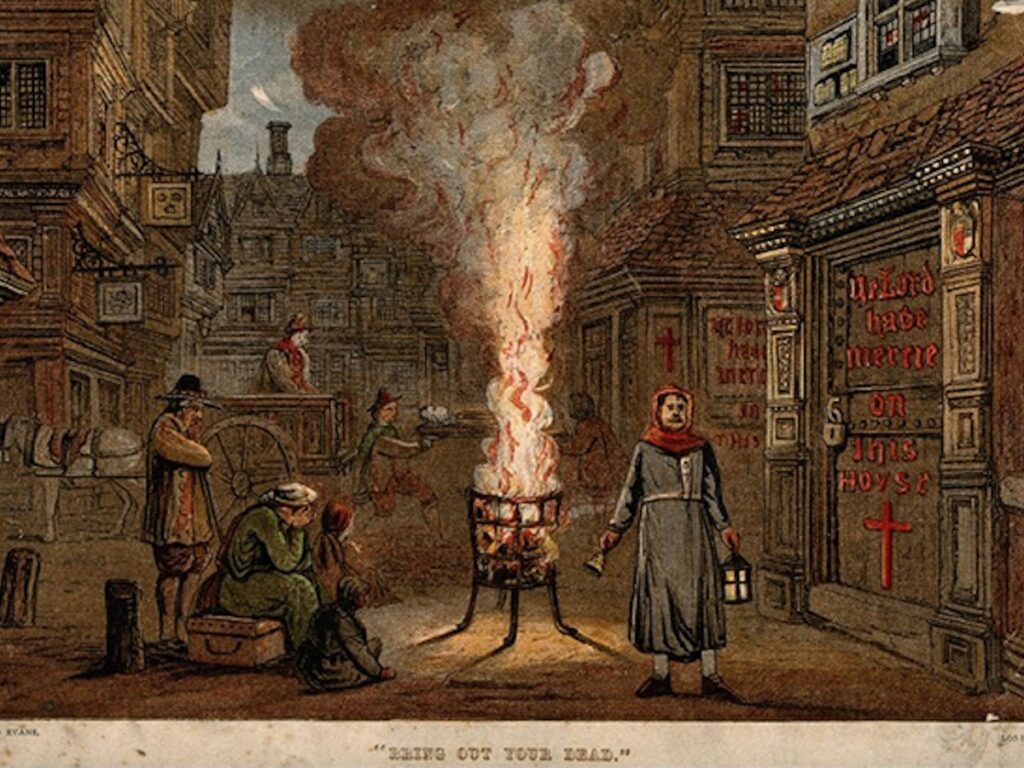

Bring Out Your Dead

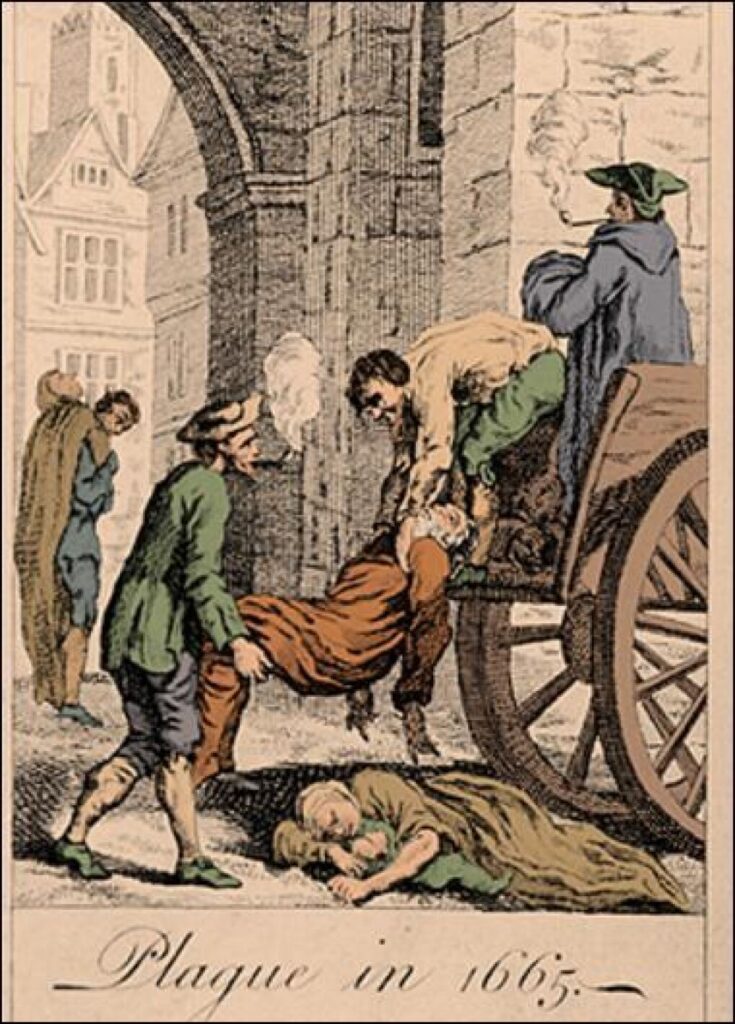

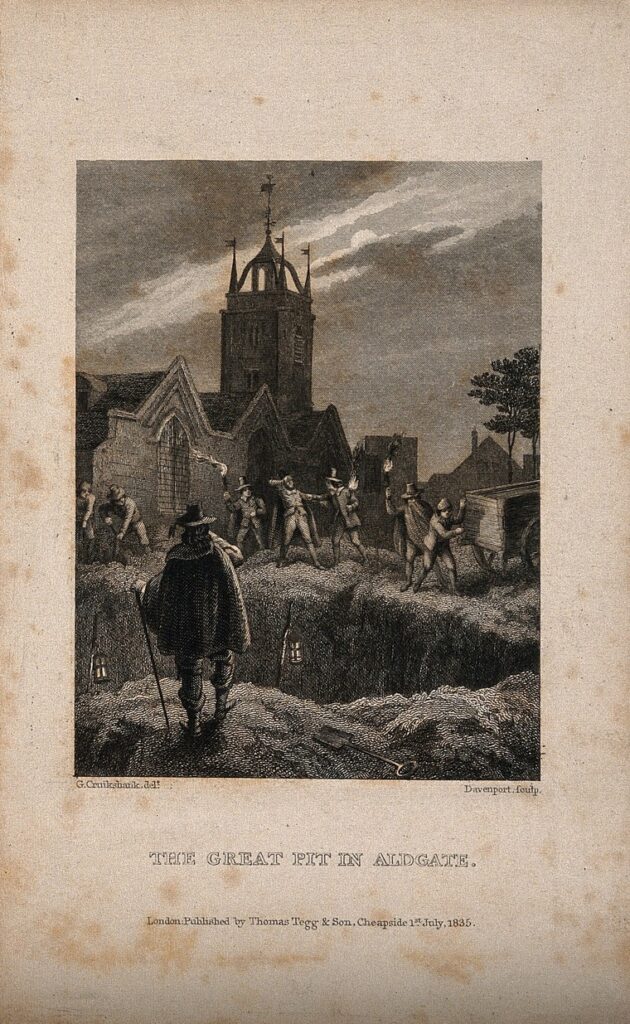

London’s churchyards, rapidly filled with fresh graves, were soon replaced by deep pits dug in unconsecrated wasteland beyond the city limits. Before burial, the bodies were covered with quicklime as a precaution. Fearing that the scale of death would provoke panic, the authorities restricted the collection of corpses to the night hours.

Families carried the bodies of their loved ones outside at the cry of “Bring out your dead!” shouted by grave-diggers perched upon their carts. Soon the number of deaths overwhelmed the city’s capacity to respond, and bodies began to pile up against the walls of houses, awaiting the night patrol. The law was hastily amended to permit the collection of corpses during daylight hours as well. To avoid direct contact, grave-diggers commonly used iron hooks to drag the dead to the cart.

Mass graves, meanwhile, became heaped with decomposing bodies due to a lack of labour to dig new pits. London was crushed beneath the sheer speed and scale of death’s advance. Wooden coffins, used at the beginning of the epidemic, were soon abandoned in favour of sheets and lengths of rope. At the height of mortality even these were discarded, and bodies were delivered to the pits naked, in frantic haste.

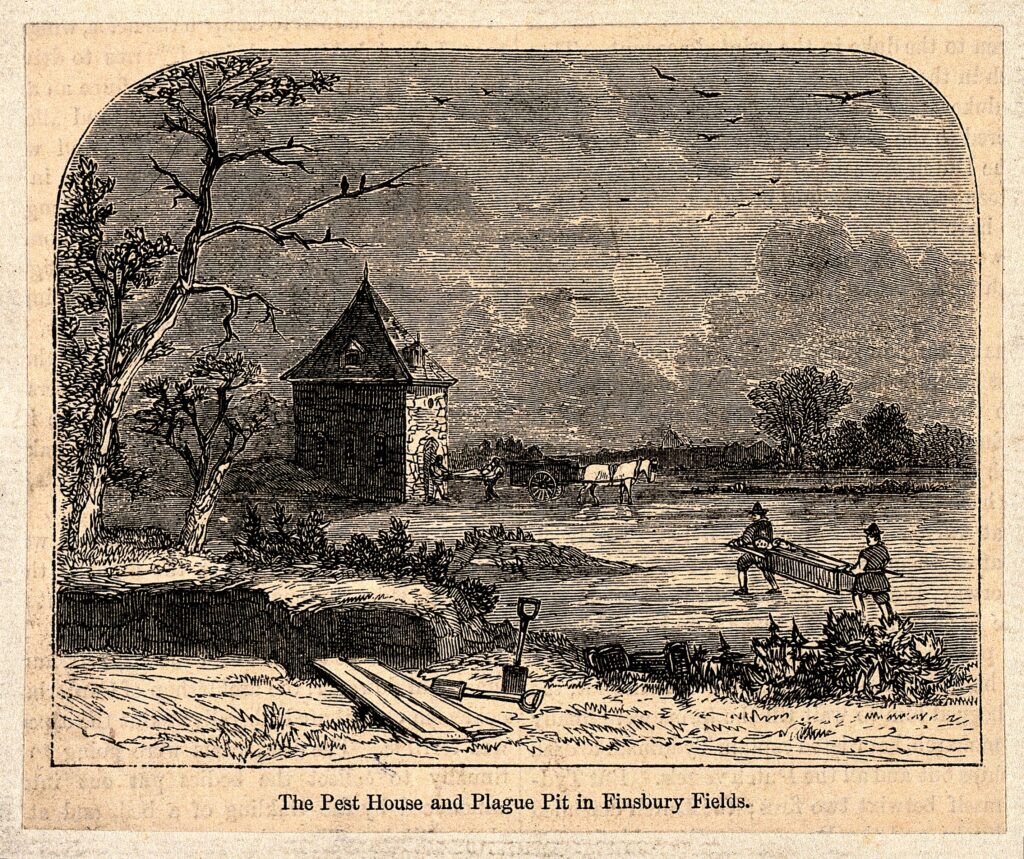

Plague Hospitals

Since the reign of Elizabeth I, London had maintained several makeshift plague hospitals, known as pest-houses, intended to isolate the infected from the rest of the population. In the spring of 1665, the city authorities received official orders to purchase land for the construction of new facilities, as the existing hospitals had fallen into ruin. This decree suggests that, despite low early death figures, the authorities were fully aware of the epidemic’s progress from the outset.

Purging the City

At the same time, men were employed to slaughter London’s dogs and cats, believed to be carriers of the plague. It is estimated that around 40,000 dogs and 200,000 cats were killed. The measure proved disastrously counterproductive: with their natural predators gone, the rat population flourished. Curiously, historical records make no mention of any attempt to exterminate the city’s rodents.

In September, as the epidemic reached its peak, desperate authorities ordered the lighting of hundreds of fires at intervals of twelve houses, hoping that flames would cleanse the air of its poisonous, disease-bearing stench. Like so many other measures, the effort proved entirely futile.

The Plague’s Climax

In July 1665, the plague epidemic in London reached its tragic climax. During the final week of that month alone, more than 2,000 people died, while over 1,800 wealthy families fled the city. Unfortunately, the well-to-do left behind most of their servants and apprentices, who, having nowhere else to go, swelled the ranks of the poor in the overcrowded districts where the plague took its greatest toll. The Lord Mayor of London attempted to avert famine by paying merchants a premium to continue supplying food to the city, a measure that ultimately saved the population from starvation.

The district hardest hit within the city walls was St Giles Cripplegate, where uneven ground allowed filthy water to stagnate, while the nearby Moorfields served as a vast, foul-smelling dumping ground for organic waste from London’s markets. From Cripplegate, the plague spread to other neglected and impoverished areas, including St Botolph and Aldgate.

By early September, the weekly death toll within the city walls had reached a terrifying 8,000. Faced with utter helplessness, the authorities abandoned the policy of quarantining families and sealing houses for forty days, as the scale of infection far exceeded the available number of guards and nurses. The city grew unnaturally silent and bleak; empty streets slowly became overgrown with grass. Carts laden with corpses rolled towards mass graves, while the moans and cries of the dying pierced the mournful stillness.

Decline of the Plague

Weekly mortality began to decline with the arrival of cooler weather, with the sharpest drop recorded in late autumn. In February 1666, the King and his court deemed London safe enough to return to. Following the monarch’s decision, aristocrats, judges, parliamentarians, merchants and entrepreneurs streamed back into the city. Most shops and places of entertainment reopened, although cases of plague continued to be recorded regularly until mid-1666.

The plague had not yet fully loosened its grip on the capital when London was struck by another catastrophe. In early September, the Great Fire broke out, destroying most of the City of London within the walls. It is often claimed that the Great Fire finally eradicated both rats and the plague. In reality, the fire had no direct connection to the end of the epidemic.

Most plague cases were recorded outside the city walls, in poor districts on the outskirts – such as St Giles-in-the-Fields, Holborn, Drury Lane, St Martin at Long Acre, Westminster, St Clement Danes, Clerkenwell, Cripplegate, Shoreditch, Whitechapel, Stepney, Ratcliffe, Southwark and Bermondsey – areas largely untouched by the fire of 1666.

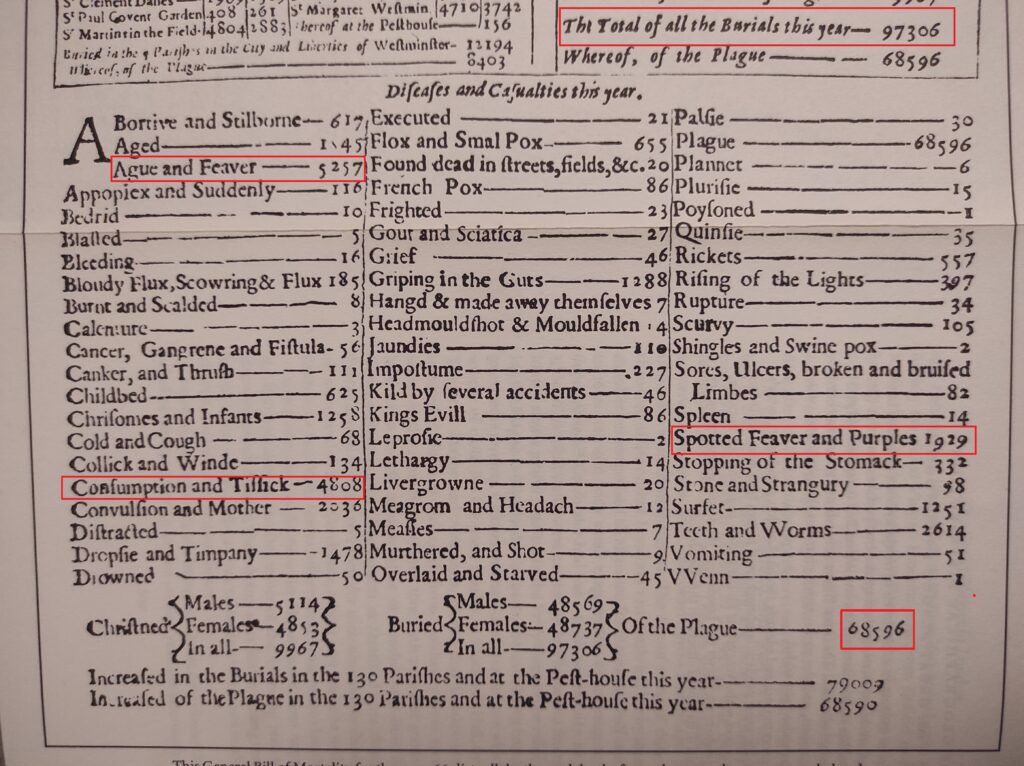

Counting the Dead

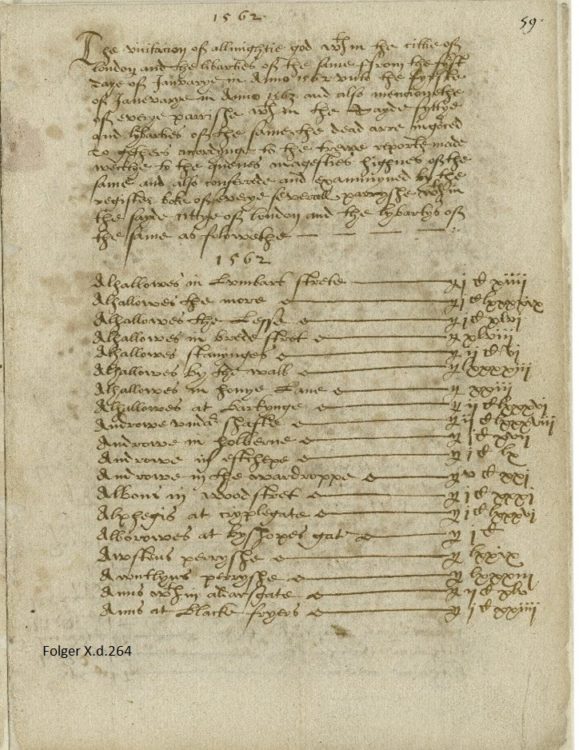

According to the Bills of Mortality for 1665, a total of 68,596 people died of the plague. Modern historians, however, believe the true figure exceeded 100,000 out of a total population of approximately 460,000 – an estimated mortality rate of 21.7 per cent. There are several reasons to suspect that contemporary figures were significantly understated.

Firstly, parish clerks may have left gaps in the records, particularly if they themselves succumbed to the plague. In addition, many documents were destroyed during the Great Fire, complicating efforts to reconstruct accurate data. At the height of the epidemic, countless victims were buried in mass graves without proper registration, due to the sheer urgency of disposal.

Moreover, religious groups such as Quakers, Jews and Anabaptists, who existed outside the established church, did not report deaths to parish authorities. As a result, the mortality of nonconformists was excluded from the official records of 1665.

Lastly, physicians at the time were under no obligation to report new infections to city authorities, even when they recognised plague symptoms in their patients. This further delayed alarms and obscured the true scale of the epidemic. Consequently, the real magnitude of the disaster was almost certainly far greater than official documents suggest.

Searchers of the Dead

Laws and procedures governing death registration during seventeenth-century plague outbreaks were far less regulated than today. Death certification and the attribution of cause were not overseen by doctors but entrusted to so-called searchers of the dead. These were women employed by parishes who, despite lacking medical training, played a crucial role during epidemics.

Like the nurses mentioned earlier, they were typically elderly, often illiterate women living on the margins of society. During outbreaks, they were required to reside in parish-assigned accommodation and were permitted to leave only to perform their duties. In the streets, they carried white staffs, warning passers-by to keep their distance.

The False Records

At the end of each day, they reported the number of deaths in their district and the stated cause of each one. Based on these reports, the city compiled the Bills of Mortality. However, these women were not always honest. For bribes from families hoping to avoid quarantine, they falsified causes of death. As a result, death registration was vulnerable to error, neglect and manipulation.

Today, we can only speculate how many plague cases were concealed under diagnoses such as smallpox, influenza, tuberculosis or consumption. Shockingly, this flawed system of death registration remained in place until 1836, when Parliament reformed the law and introduced a more formal and controlled procedure.

Fields of the Dead

Mass graves and pest-houses were profoundly traumatic for London’s poor. Many resisted the removal of the sick to places where care was minimal and burials took place in communal pits, without ceremony. Yet as the epidemic intensified and bodies multiplied, the city had no choice but to use surrounding fields, where the dead were usually buried at night, hastily and without rites.

The issue of burial space posed a particularly intractable problem. The Bishop of London, bound by canon law, refused to consecrate land not intended for permanent ecclesiastical use. On the other hand, transferring vast grounds to church ownership to allow for consecration was an impossible condition for both private landowners and the city authorities.

A City of Graves

Over time, many unmarked burial sites were forgotten, and only a handful have been officially identified by archaeologists as plague pits from 1665. Some locations cited in historical sources can no longer be precisely traced. Various urban legends and theories circulate online about other possible sites, but without firm evidence.

Those seeking morbid adventures in the capital can safely assume that much of central London rests, to some extent, upon layers of the dead – and that many small gardens and public squares were once churchyards of forgotten, vanished churches. Their lawns often rise noticeably above pavement level, the result of centuries of earth piled atop buried bodies. With that in mind, I wish my fellow dark tourists a most enjoyable picnic on London’s green spaces.

Discover more from London Macabre

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.