Cleopatra’s Needle is an ancient red granite obelisk that now stands on the Thames Embankment, near Waterloo Bridge. Though its presence beneath London’s clouded skies seems somewhat unexpected, it is not the only Egyptian obelisk to have found its way, quite improbably, to the other side of the world. Monuments of this kind were usually built in pairs and placed on either side of a temple’s entrance. Such was the case with Cleopatra’s Needle, whose identical counterpart has stood in New York’s Central Park since 1881.

Origin of the Artefact

Despite its name, London’s obelisk has little to do with Cleopatra herself, for it was created more than a thousand years before her reign. It was carved in the Egyptian city of Heliopolis around 1450 BC from stone quarried in the Nile Valley near the First Cataract. The monument was commissioned by Pharaoh Thutmose III, who ordered that a central line of hieroglyphs be inscribed in his honour – these can still be seen on all four sides today. The two outer lines of inscriptions were added later by Pharaoh Ramesses II, commemorating his military triumphs.

Around the 12th century BC, the twin obelisks were moved to Alexandria and placed before a temple, which Cleopatra is thought to have built in honour of Mark Antony. And that, it seems, is where the famous queen’s connection to the monument begins and ends.

A Gift to the British Empire

The obelisks remained in place until 1877, when the Ottoman governor of Egypt and Sudan, Muhammad Ali, decided that the 200-ton monument would make a splendid gift for the British Empire. It was meant to commemorate Lord Nelson’s victory over the French at the Battle of the Nile in 1798, as well as Sir Ralph Abercromby’s triumph at the Battle of Alexandria in 1801. The unusual present was received with gratitude – but the obelisk stayed in Alexandria for another sixty years. Though delighted with the gift, the British were less eager to finance its immensely costly transport to London.

The Impossible Journey

Sixty years later, the plan finally began to take shape, thanks to the combined efforts of General Sir James Alexander, engineer John Dixon, and the deep pockets of Sir William James Erasmus Wilson – a distinguished anatomist and dermatologist who contributed the staggering sum of £10,000 (equivalent to roughly a million pounds today) to finance the endeavour.

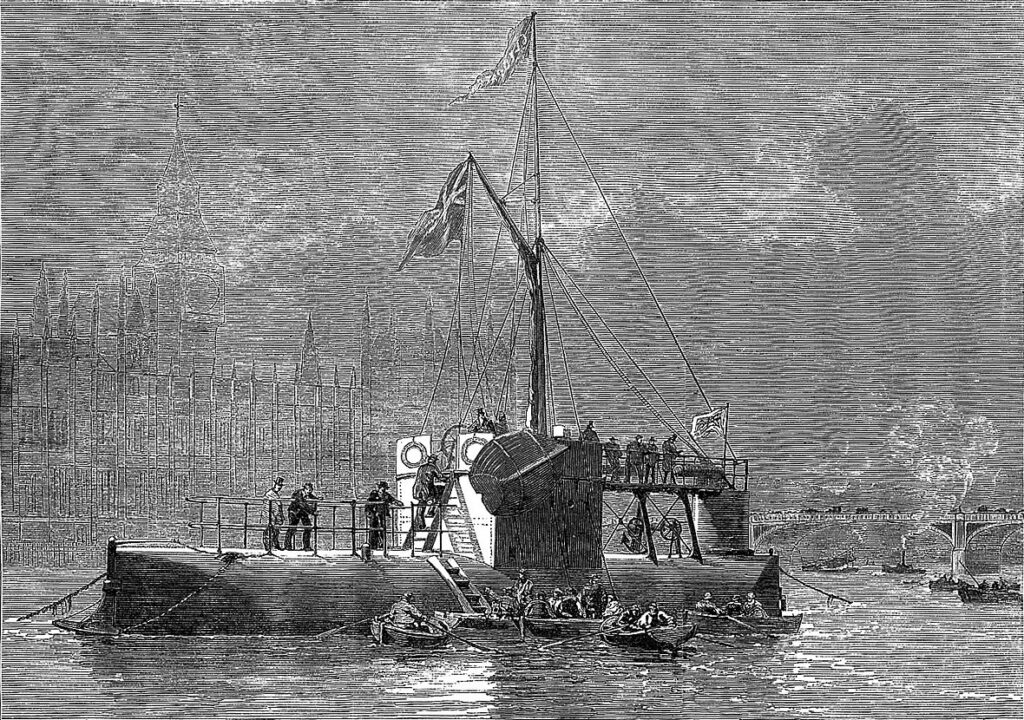

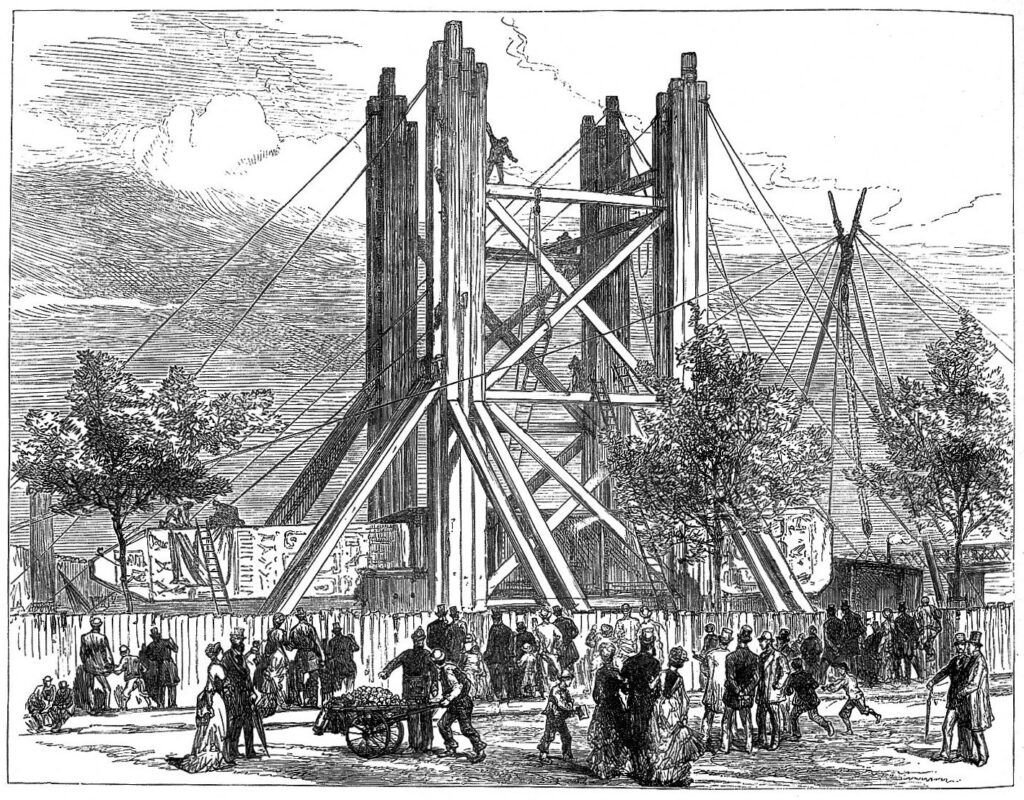

Dixon’s ship design was an extraordinary blend of ingenuity, engineering skill and sheer faith. After excavating the stone monument from the sand where it had rested for nearly two millennia, the obelisk was encased in a watertight metal cylinder, built around it on the very spot where it lay. Using cranes, ropes and wooden ramps, the cylinder was then rolled to the sea. There, the massive “cigar” was fitted with a mast, rudder and steering mechanism, christened Cleopatra, crewed by a small team under Captain Carter, and attached to a steamship, Olga, commanded by Captain Booth, who was to tow the vessel all the way to London.

It was an ambitious plan – especially as Cleopatra had been constructed in a London shipyard and transported in parts to Egypt, where it was assembled around the obelisk without endangering the ancient stone. Yet the greatest challenge still awaited them: the sea itself.

Across the Waters

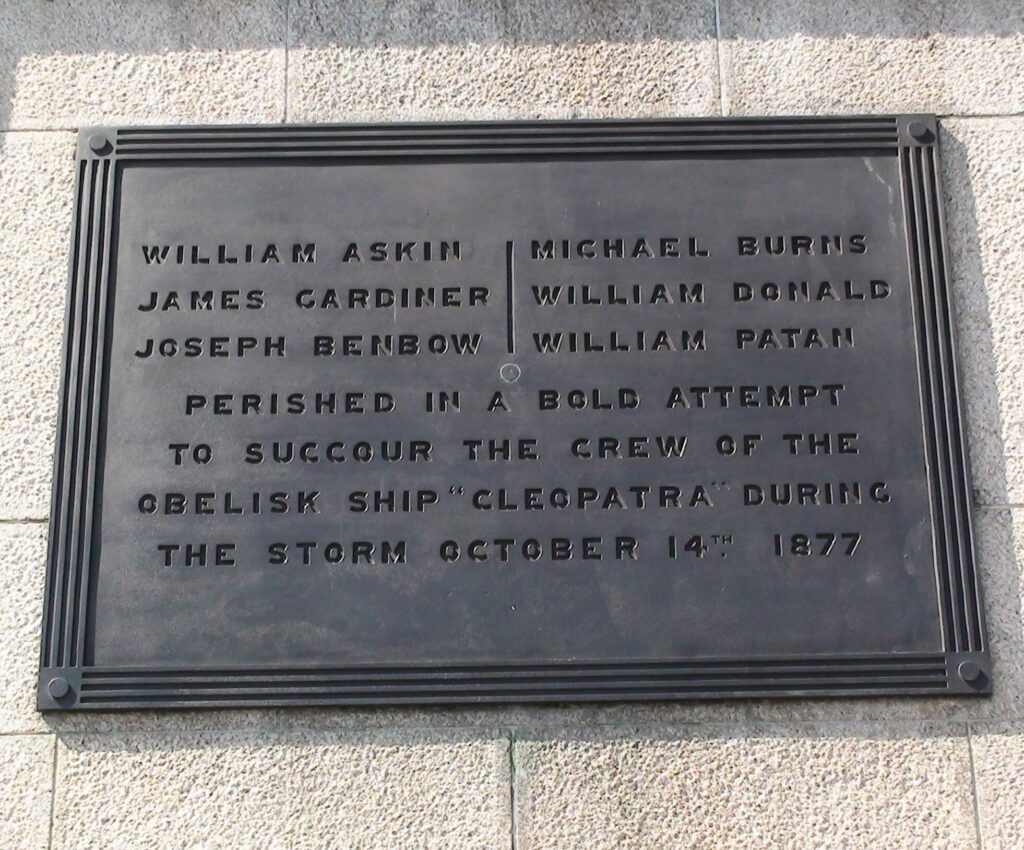

On 14 October, as the ships entered the Bay of Biscay off the western coast of France, a violent storm erupted. The Cleopatra, towed behind Olga, went out of control in the raging sea. Captain Booth sent six volunteers in a lifeboat to reach Cleopatra and rescue her crew. Tragically, they never managed to grasp the lines thrown to them; the lifeboat capsized and all six men vanished without trace into the foaming waves. Their bodies were never recovered, but their names are now inscribed on a bronze plaque at the base of the obelisk.

Determined to save those still aboard, Booth manoeuvred Olga closer and successfully cast new lines. Captain Carter and his crew escaped in relief. Yet Booth was forced to cut the tow rope and let Cleopatra drift away – the storm unrelenting, the situation hopelessly beyond control. London received word that the priceless artefact had been lost at sea. But the obelisk was not so easily claimed by the deep. Days later, to the astonishment of all, Cleopatra was found intact, drifting off the northern coast of Spain. The monument finally reached London in January 1878.

The Shadow of a Curse

Even before the obelisk was erected on the Embankment later that year, it had already gained a dark reputation among Londoners. Sailors who had witnessed the deaths in the Bay of Biscay and the subsequent miraculous reappearance of Cleopatra whispered of an Egyptian curse and sinister omens.

Victorian London was then gripped by an obsession with Egyptology, the mysteries of the pharaohs and supposed proof of their immortality and time-defying powers. It was hardly surprising, then, that many believed the disturbance of such an ancient relic would bring with it strange and unholy consequences. Some even claimed that the very soul of Ramesses II was trapped within the red granite itself.

Dark Echoes on the Thames

Since the obelisk took its place upon the Thames shore, the surrounding area has acquired an unsettling reputation for attracting suicides. Veteran officers of the Thames River Police have long claimed that more suicides and attempted suicides occur near the monument than anywhere else along the river.

There have also been persistent reports of a mocking, muffled laughter heard near the obelisk at night. The sound has been linked to the apparition of a tall, naked man, seen on several occasions. The ghost reportedly rushes out from behind the monument and plunges into the river – yet no splash is ever heard. The first such accounts appeared mere weeks after the installation, leading many to believe the ghost was one of the sailors who died in the Bay of Biscay.

The Nightmares of Miss Davies

Another tale from nineteenth-century London tells of a twenty-seven-year-old woman, Miss Davies of Pimlico, who around 1880 was walking along the Embankment when she suddenly felt an irresistible pull towards Cleopatra’s Needle. As she approached, she heard a scornful laugh that left her legs paralysed with terror. Stumbling forward, she fell into the river, but was rescued by a vagrant who had witnessed the scene from afar.

Though physically unharmed, Miss Davies was plagued thereafter by terrible nightmares. In them, she saw a tall woman with a white face and dark almond-shaped eyes, clad in crimson robes. The spectre opened her mouth to reveal razor-sharp teeth, and the skin of her face peeled away as if torn off. Her attire suggested she might have been an Egyptian priestess or noblewoman. Miss Davies was convinced that her visions were linked to the cursed obelisk.

A Warning from the Future

A more recent account tells of a river patrol officer who, one night near Cleopatra’s Needle, heard hurried footsteps behind him. Turning, he saw a well-dressed woman in visible distress. She implored him to follow her – she had seen someone standing on the wall above the river, seemingly ready to jump. The officer ran after her and indeed spotted a figure poised to leap. He lunged forward just in time, pulling the person to safety. To his astonishment, he realised it was the very same woman who had moments earlier fetched him for help. She was identical in every way, wearing the same clothes. When he looked around, the first woman had vanished without a trace.

What Lies Under the Stone

City officials buried a time capsule beneath the Needle’s pedestal, intended to preserve the spirit of the Victorian era for generations yet to come. Inside were twelve photographs of Britain’s most beautiful women, a box of hairpins, a box of cigars, several pipes, a baby’s feeding bottle, toys, a razor, a full set of current British coins, several copies of the Bible in different languages, a railway timetable, a map of London, ten daily newspapers and a variety of other everyday objects.

Some speculate that the source of the obelisk’s haunting phenomena may not be the ancient monument itself, but one of those seemingly trivial items – perhaps cursed or burdened with the misfortune of its former owner.

Whatever the truth, Cleopatra’s Needle remains one of London’s most fascinating monuments – and those who have laid a hand on its cold granite on a windy November night will understand why such stories are born in the first place.

Discover more from London Macabre

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.