Few places revealed the realities of Victorian poverty as starkly as London’s East End. Behind the narrow alleys and soot-blackened tenements lay a world of hunger, makeshift meals, and street-side dining born of necessity. Here, food was not a matter of pleasure but survival – a daily struggle waged with a penny in hand and hope for something hot to eat. Yet amid the smoke and grime, the streets of Whitechapel and Spitalfields buzzed with life: the cries of vendors selling roasted potatoes, the scent of fried fish, the clatter of coffee cups, and the murmur of countless accents blending into one. This was where London’s street food culture was born – improvised, resourceful, and as diverse as the city itself.

Eating in the East End

The diet of the poor in Victorian East End London was shaped above all by the appalling living conditions in the local slums. Owning a private kitchen was an unattainable dream for most residents. A family renting a single room in a tenement might have access to a modest cooking recess, shared with a dozen or more other families crammed into the same building.

A few households had access to a stove and basic utensils, but the majority possessed neither plates nor spoons. As a result, meals eaten at home were often limited to bread and gruel, while everything else had to be bought in the street. The monotonous diet was made more bearable by the sheer number of street stalls selling cheap snacks and drinks. More substantial meals could be found in coffee houses and eateries, while evenings were spent over beer in the local pub.

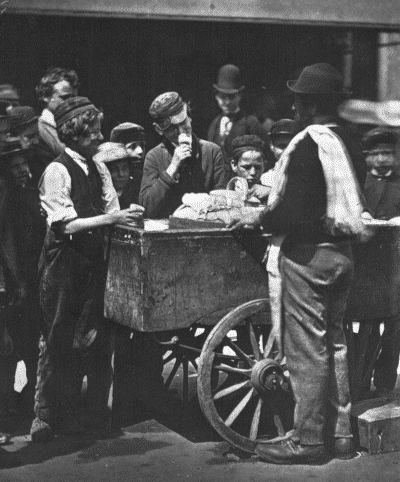

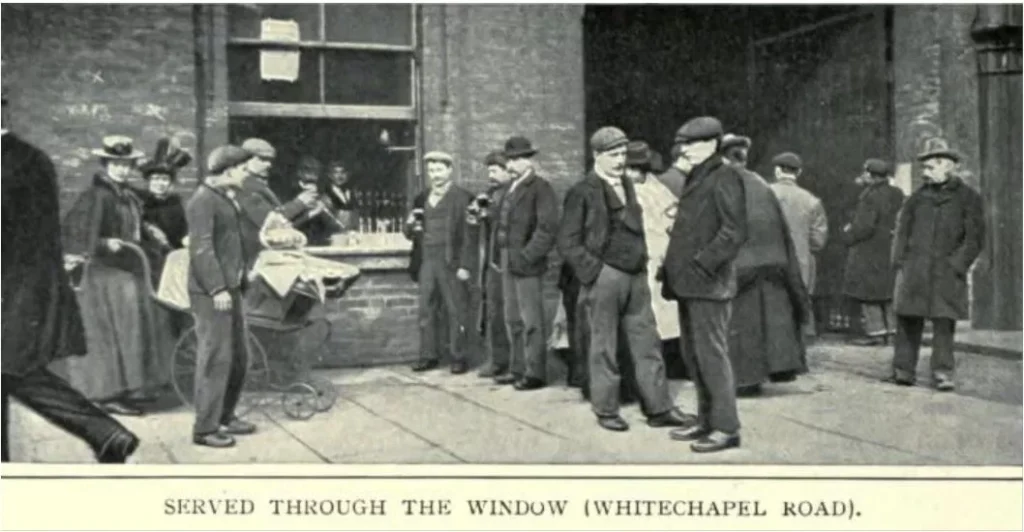

All food sold in the East End was simple, quick, and made from the cheapest ingredients available. It could be eaten on the go, or taken away and consumed during the day. It required no cutlery or crockery. With the influx of poor labourers – many living in lodging houses and shelters – the demand for London’s street food grew even further. By the mid-nineteenth century, over 6,000 itinerant vendors were working across the city’s poor districts, selling oysters, eels, pea soup, fried fish, meat and fish pies, puddings, sheep’s trotters, pickled whelks, roasted potatoes, gingerbread, teacakes, cough sweets, ice cream, ginger beer, hot cocoa, and peppermint water.

Breakfast of the East End Poor

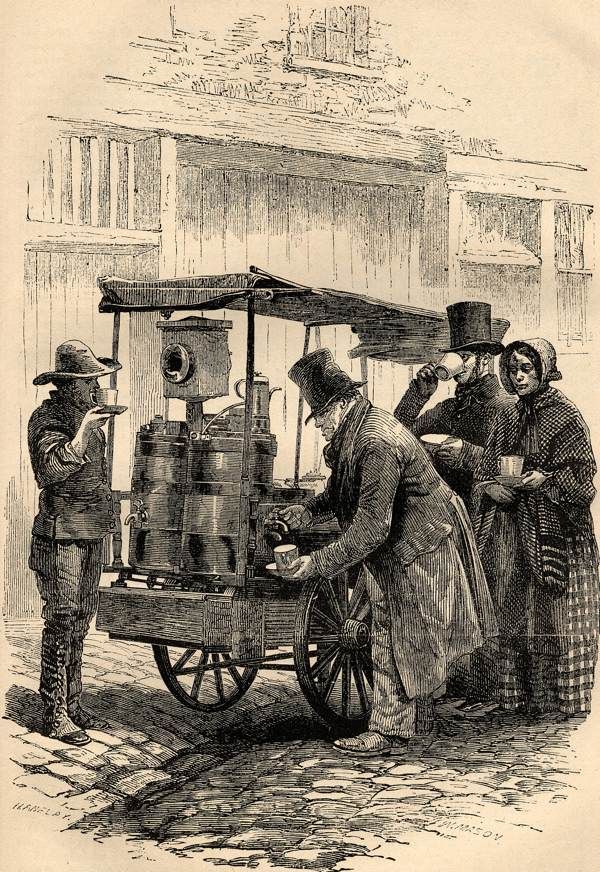

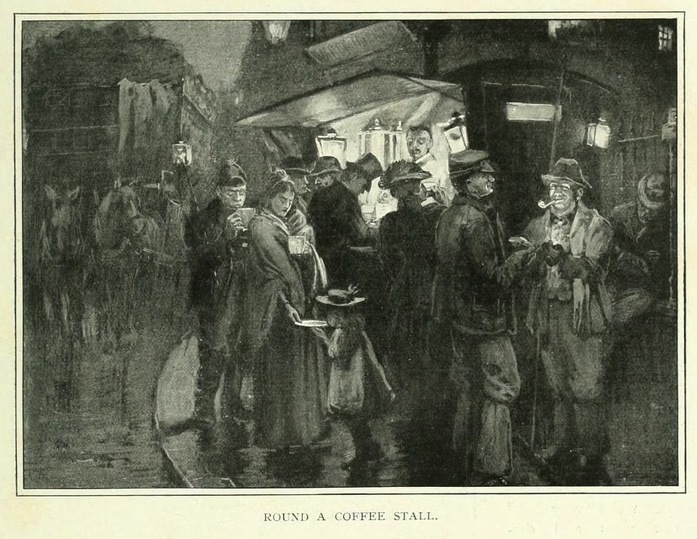

Breakfast in the East End was most often eaten outdoors, at small coffee carts. The sale of hot drinks became widespread in the 1840s and was carried out mainly by women. Mobile stalls were stationed at busy street corners, near markets and factories. The biggest takings were made early in the morning, when workers and traders set off to work, and late at night, when the homeless and drunkards sought warmth and comfort.

The entire stall consisted of a cart fitted with several tin containers of hot drink, kept at temperature by a small coal fire, and a set of mugs for customers. The coffee itself was of poor quality – half coffee, half chicory – and was boiled with peeled carrots to give it a touch of sweetness. It was cheap, and therefore immensely popular. For one penny, one could buy a small cup of coffee and two slices of bread and butter.

Better-off customers might add a slice of currant cake or a sandwich filled with ham, hard-boiled eggs, and watercress. Those who chose to eat at home usually settled for a piece of bread, sometimes with a bit of butter, washed down with a glass of beer.

Traditional dark ale was the most popular drink among the poor and was consumed habitually throughout the day by both adults and children. Beer provided extra calories and essential minerals – priceless in a diet made up mostly of bread and potatoes. With the rise of the Victorian temperance movement, supported by the upper classes, morning beer was gradually replaced by coffee and tea. Paradoxically, this had a harmful effect on the health of the poor, as these drinks were of low quality and offered no nutritional value.

Traditional Breakfast Pastries

East Enders with slightly larger budgets could occasionally diversify their breakfast by buying English muffins or round, soda-leavened yeast cakes known as crumpets from street vendors. Both were served with butter and, for an extra charge, jam. During Easter, the hot cross bun – sweet, spiced, and dotted with raisins or currants, marked with a symbolic cross – was a seasonal favourite.

Pastries were sold mainly by young boys, often the sons of bakers, who walked the London streets from dawn carrying baskets lined with thick cloth to keep the bread warm. The arrival of the seller was announced by a small bell, a familiar sound across the capital. The best sales were made early in the morning and around five in the afternoon, when it was time for tea.

Daytime Street Food

During the day, London’s poor turned to quick and cheap snacks, replacing the morning coffee carts at street corners. The cheapest – and therefore most popular – were seafood and shellfish caught near the Thames estuary. Among the best-selling snacks were cockles (heart-shaped clams) and winkles (sea snails).

Street stalls served portions of cockles in paper cups, while cafés offered them as side dishes. Winkles were kept alive and boiled in small batches as needed. In the evenings, shellfish vendors would even visit public houses, serving clams to beer-drinking patrons. A mix of shellfish seasoned with salt and white pepper was a near-obligatory accompaniment to a pint of ale for every self-respecting East End worker.

Today, such traditional fare is increasingly rare. Pickled cockles can still be found as starters in a few Brick Lane pubs, which otherwise specialise in oysters and more refined seafood. For whelks, one must now travel as far as Charlton.

The Eels of the East End

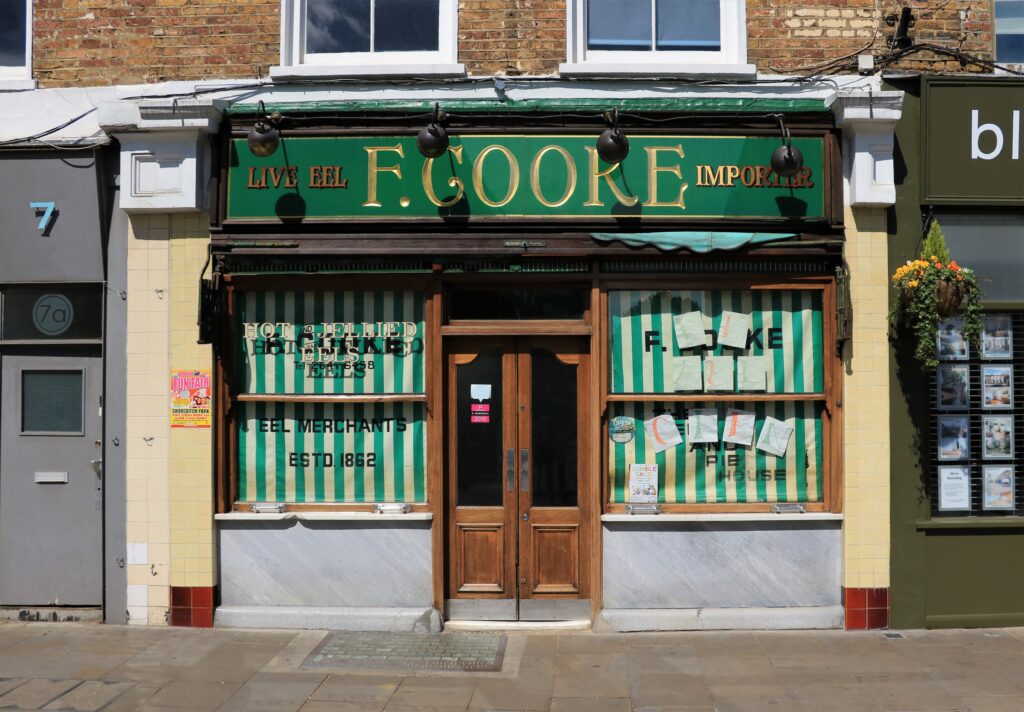

Jellied eels are one of the most famous East End delicacies, known since the eighteenth century and still eaten in the capital today. Eel was a cheap, readily available, and nourishing fish that quickly became a staple of the poor man’s diet.

In Victorian times, the Thames was home to a vast population of European eels – the only fish capable of surviving in the foul, polluted waters filled with waste and sewage. The fish, chopped up with its skin, was boiled in a spiced broth with vinegar, nutmeg, and lemon. Being fatty and gelatinous, the eel released collagen into the liquid, which turned to jelly once cooled. Served cold with vinegar, salt, and white pepper, it became an iconic dish of the East End.

Some of the oldest cafés selling traditional eels can still be found around Spitalfields, Poplar, and Bethnal Green. These places remain popular with locals, although today’s eels are sourced from coastal towns rather than the Thames. There’s still a saying that anyone who hasn’t tried this peculiar delicacy at least once cannot call themselves a true East Ender – or cockney.

Roasted Potatoes

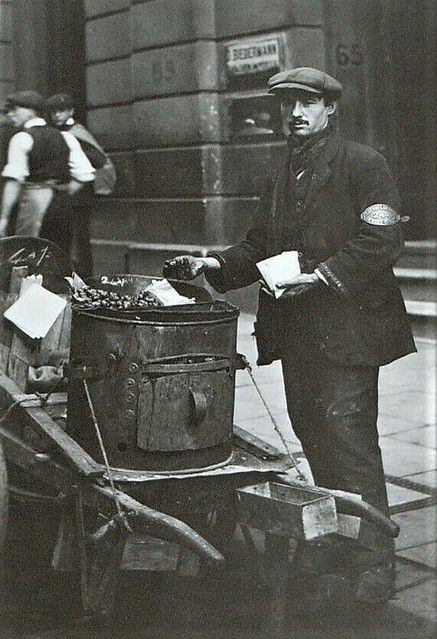

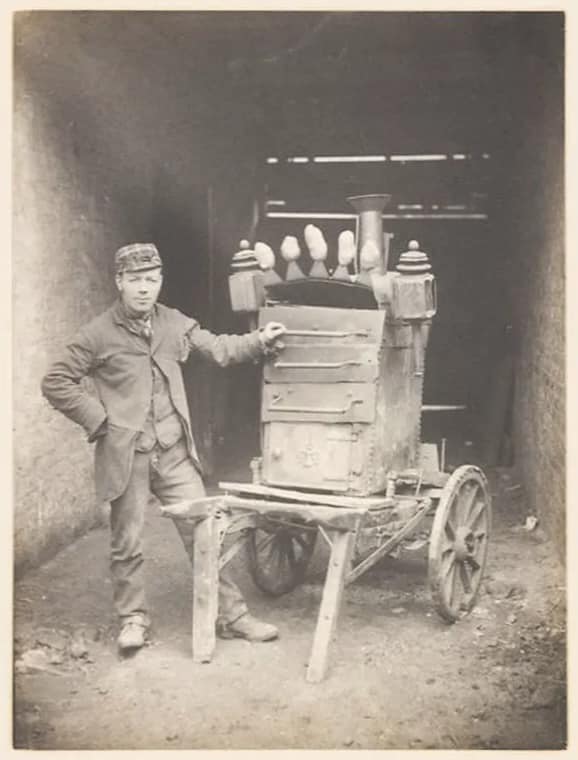

Equally popular were the roasted potato stalls, open roughly from August to April. Vendors would buy large potatoes at the market, wash them, and pay a baker eight pence to roast them in their skins for about an hour and a half. The roasted potatoes were then carried home under heavy cloth, transferred into a half-open tin can, and placed in a water bath heated by a coal fire.

Served hot with salt, pepper, and butter, the humble baked potato was the cheapest way to warm cold hands – and as such, caused quite a sensation on the streets of nineteenth-century London. The modern version, known as the jacket potato, is now a staple of every British café serving breakfast, typically topped with baked beans, butter, or grated cheese.

Dinner in the East End

The main meals of those living on the brink of poverty usually consisted of bread and a few basic items. Sprats were among the cheapest “luxury” goods available to the poor – sold at the market for about ten weeks from November onwards, and eaten daily during that time.

Other popular combinations included smoked or salted herring with potatoes or bread. Fried fish stalls often offered cheap saveloy sausages, made from highly seasoned minced pig brains, distinguished by their deep red colour and pungent smell.

At other stands, one could buy hot pies filled with seasonal fruit, minced meat, or eels. The eel pies were the cheapest and least desirable, avoided especially by fishmongers who knew the risks of stomach illness from spoiled fish.

The very poorest could buy small scraps of inferior meat, cut from better joints and displayed by butchers at the end of the day. For a modest fee, this could be cooked in a nearby pub. A pint of dark beer or a shot of gin usually accompanied dinner – helping to explain the countless alcoholics that filled the slums of Victorian East London.

The Birth of Fish & Chips

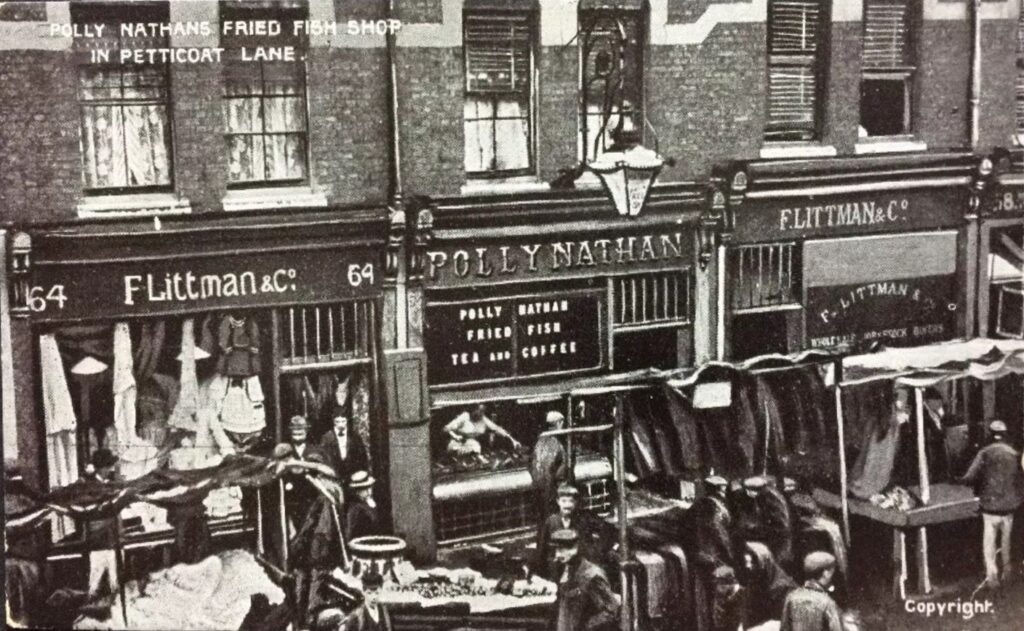

Fried fish was known to London’s working classes from the early Victorian era. The development of the railway facilitated the transport of goods to the capital and boosted imports from seaside towns. Prices dropped, making domestic fish – especially herring – an essential part of the poor man’s diet. Mackerel, plaice, and sole were also common.

Fish coated in a batter of flour and water and fried in lard were sold at small street stalls, especially on Saturday evenings and Sundays, near pubs. The fish was served wrapped in newspaper with a slice of bread, which over time was replaced by chips. Containers with salt, pepper, and vinegar were provided for customers.

These Victorian stalls gave birth to today’s Fish & Chips – the national dish of Britain, loved by people of all ages and backgrounds. The first London shop to sell fried fish with potatoes opened in 1860 on Cleveland Way in the East End. It was founded by Joseph Malin, a Jewish immigrant. Fish & Chips quickly became one of the most popular working-class meals and remain so to this day. Interestingly, the practice of wrapping the dish in newspapers ended only in the 1980s, when the risk of ink contaminating the food was finally acknowledged.

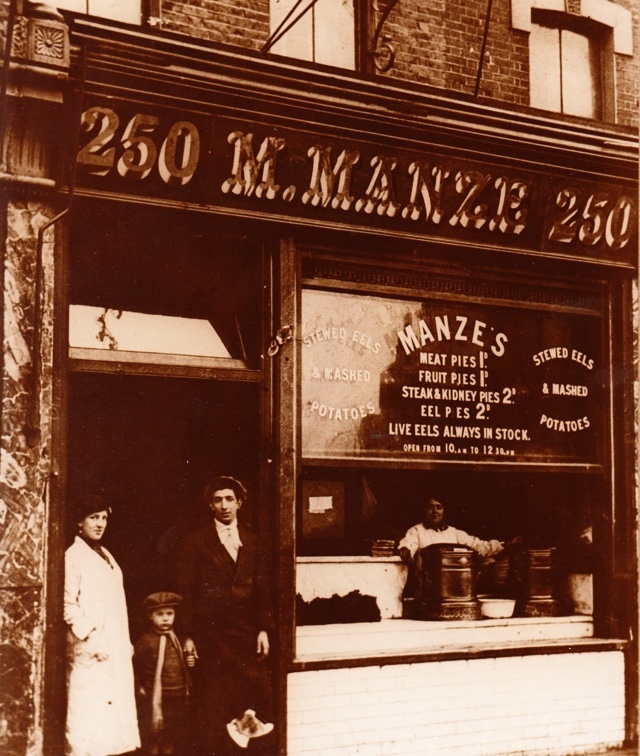

Traditional Pie & Mash

Pie & Mash is another traditional poor man’s dish originating in nineteenth-century East London. Its popularity stemmed from how easily it could be carried in a pocket and eaten during a lunch break without a plate.

The crust, made with beef suet, was filled with minced eel stew or cheap minced mutton. Initially sold at street stalls, pies also came in sweet versions with seasonal fruit. Later, cafés began serving meat pies with mashed potatoes and a green parsley sauce known as eel liquor, made from eel stock.

Many traditional Pie & Mash cafés still operate in East and South London today. Their interiors have retained a distinctly Victorian character: white tiled walls, mirrored décor, and marble floors, tables, and counters – spotlessly clean and easy to maintain.

Jewish Beigels of Brick Lane

The Jewish presence in nineteenth-century Whitechapel brought the beigel into East End cuisine. The history of the beigel on Brick Lane dates back to the late nineteenth century, when Jewish immigrants from Poland arrived in London fleeing persecution in Eastern Europe.

By the 1930s, Brick Lane was home to a thriving Jewish community, full of cafés serving traditional dishes. Although the Jews later moved north, authentic beigel bakeries remain to this day. Beigel Bake and Beigel Shop are the last two establishments recalling a time when street signs were written in Yiddish, the present mosque was a synagogue, and kosher butchers traded where Bengali curry houses now stand.

Traditional Jewish beigels are made from yeast, flour, water, salt, and a sweetener. Their distinctive round shape with a hole in the middle and the method of boiling before baking give them a chewy texture and crisp crust.

Modern mass-produced American versions, known as bagels, are steamed rather than boiled, resulting in a soft, bread-like texture. The spelling “beigel” is therefore used to distinguish the traditional Jewish original from its Americanised counterpart.

At the Brick Lane cafés, the most popular fillings include chopped pickled herring, cream cheese with smoked salmon, and the undisputed favourite: salt beef with gherkins and fiery English mustard. The salt beef – perfectly tender and savoury brisket – is so beloved that Beigel Bake produces over 7,000 beigels every day, with long queues constantly forming outside. Fortunately, both shops are open 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Victorian Sweets and Puddings

Desserts of the working class were typically limited to bread pudding, popular among the city’s poor since the eighteenth century. The pudding consisted of stale bread soaked in milk, mixed with raisins and sugar, and baked in the oven.

Another favourite was jam roly-poly, known colloquially as dead man’s arm or dead man’s leg. Originating in the early nineteenth century, it was made from rolled suet dough spread with jam, wrapped in cloth (often the sleeve of an old shirt, hence the nickname), steamed, and sometimes baked for a crisp crust. The first official recipe appeared in 1845 in Eliza Acton’s cookbook.

Modern versions no longer require grating hard beef suet, as ready-made alternatives are available. Interestingly, despite today’s obsession with healthy eating, the main British producer of suet – Atora – still sells an astonishing 2,300 tonnes of it every year.

Though many of the alleys and street corners of Victorian London have long vanished, much of its humble fare endures. Pies, eels, puddings and pickles – once the food of the poor – remain woven into the city’s culinary memory. Eaten now more for nostalgia than necessity, they still tell the story of London that fed itself with grit, ingenuity, and a stubborn appetite for life.

Discover more from London Macabre

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.