The history of Soho is marked by stark contrasts. Before cholera and poverty left their indelible mark on the district, the area had already undergone a long and turbulent transformation. In the seventeenth century it was an enclave of aristocracy on the city’s fringes, home to more than a hundred noble families living in luxury and splendour.

By the eighteenth century the elite had drifted westward to fashionable Mayfair, and Soho’s grand houses began to be divided into modest lodgings. In their place came impoverished artists, craftsmen and immigrants; among those who passed through the district were Wagner, Liszt, Mozart and Karl Marx. Ornate gardens gave way to scrap yards and makeshift outbuildings.

In 1854, long forgotten by most, Soho briefly returned to public attention during one of the deadliest cholera outbreaks in London’s history – an event that would forever shape the development of medicine and public health.

On the Eve of the Epidemic

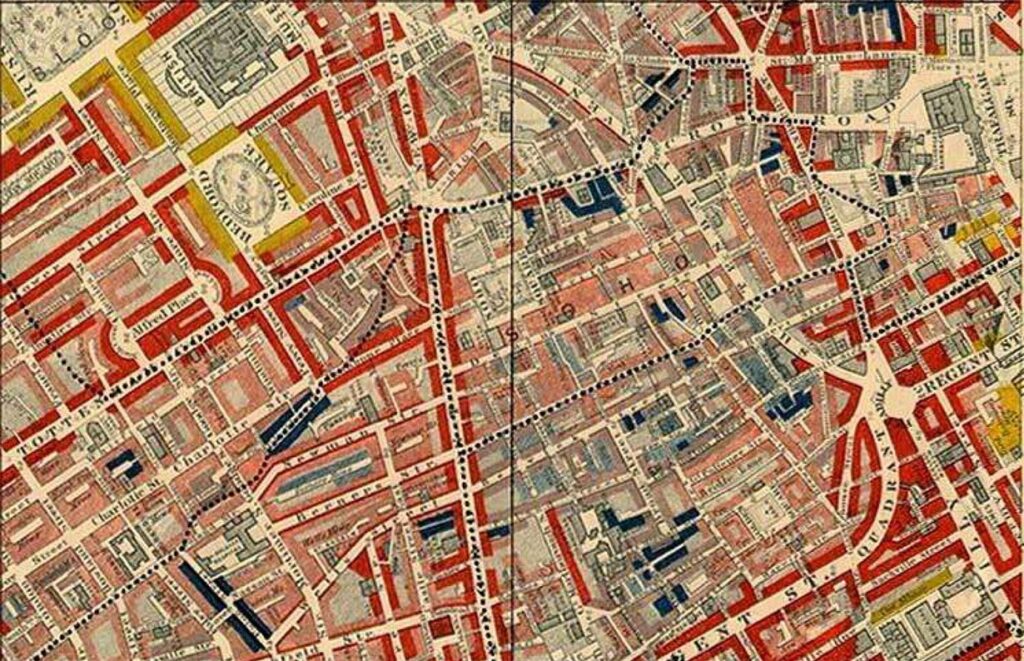

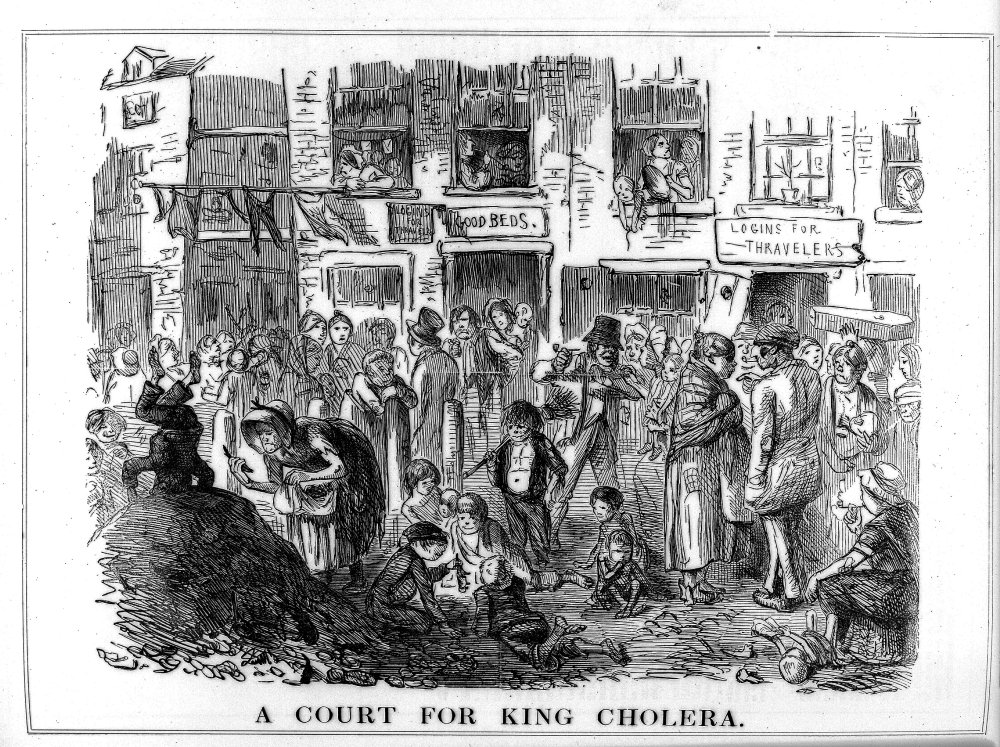

In 1854, the area around Berwick Street was one of the most densely populated parts of the city, filled with visionaries, eccentrics and radicals living in decaying former mansions. The cramped maze of two- and four-storey houses, artisan workshops, slaughterhouses, tanneries and small factories producing soap, shoes and pickles – all without proper drainage or a safe supply of drinking water – provided the perfect conditions for an outbreak to spread. Most residents lived in poverty, and the district formed a grim anomaly: an island of stench and destitution in the very heart of the affluent West End.

The Waste Removal System

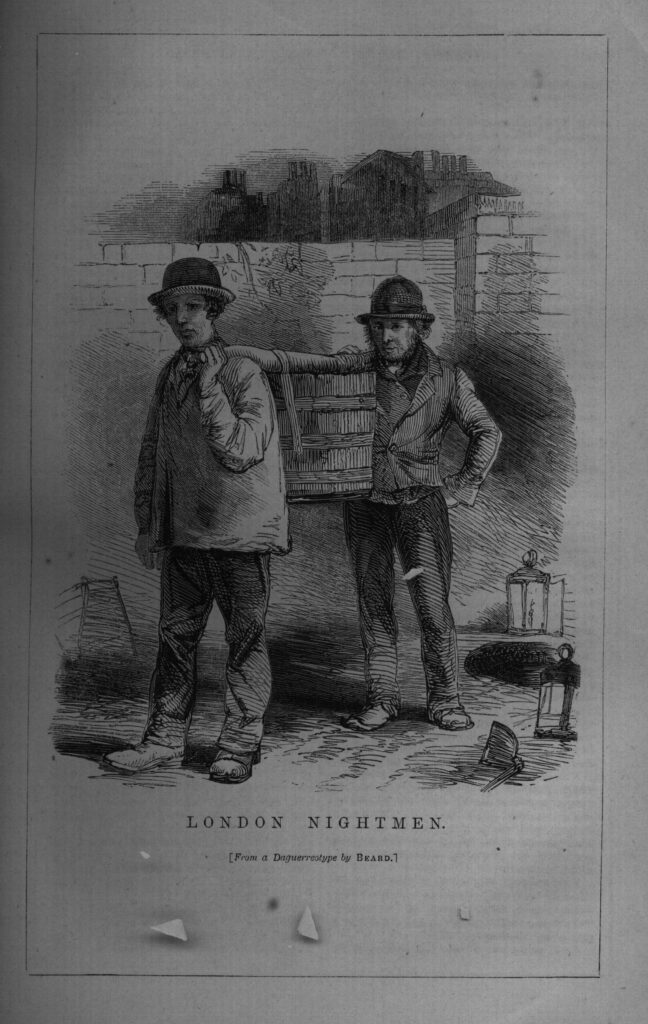

To understand the true character of Soho during the 1854 cholera outbreak, one must consider the system of waste disposal at the time. Victorian London still lacked a city-wide sewer network. The removal of human waste, a practice dating back to the early Middle Ages, fell to labourers known as “night soil men.”

Hired by property owners as subcontractors, they emptied overflowing cesspits at night in teams of four. Using buckets, they extracted excrement from open pits and transported it under the cover of darkness to be sold to farms on the city’s outskirts. It was one of London’s oldest urban professions, essential to the city’s survival. Though it was well paid, it was simultaneously foul and hazardous work. Cases of workers drowning in cesspits – such as one recorded in 1326 – were far from uncommon.

Sanitary Conditions in London

The medieval system of collecting waste and using it as fertiliser, which had served the city for centuries, could no longer cope by the early nineteenth century. London had grown into Europe’s largest metropolis, stretching far beyond the old Roman walls. For the night soil men, this meant much longer journeys to the suburban farms, now located not just a few but many miles from the centre. As a result, the cost of emptying a cesspit rose sharply. In Victorian times, a single removal could cost a shilling – nearly double the average daily wage of a manual labourer. Therefore, for many Londoners, paying for waste disposal was a far greater burden than living above a leaking, overflowing cesspit.

Filth and Decay

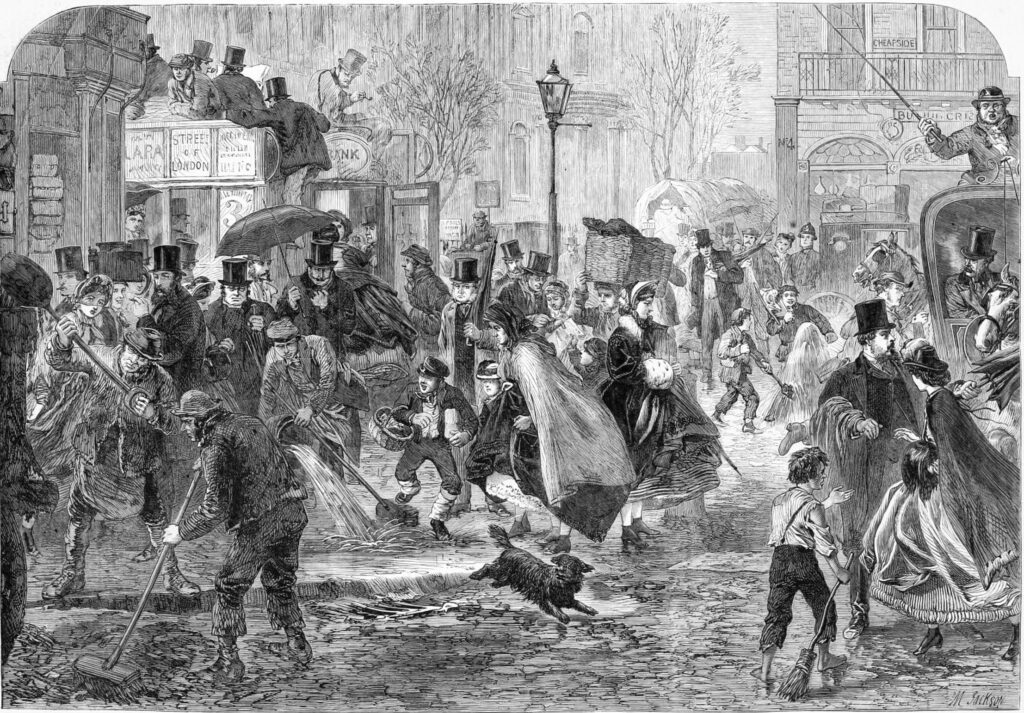

Numerous historical sources meticulously document the state of London at this time. People used their cellars to empty chamber pots when the cesspits could hold no more. Many cellars were filled with excrement up to the level of the pavement. Once the cellars became unusable, residents turned to inner courtyards and backyard gardens. The stinking sludge from overflowing privies lay 15-20 centimetres deep, forcing tenants to navigate improvised walkways to avoid wading through filth. In the Spitalfields area, at the junction of several streets, a mound of manure and waste grew as large as a local house. Beside it, an artificially dug pond served as the daily dumping ground for the contents of nearby residents’ chamber pots.

What is Cholera?

Cholera is an acute diarrhoeal disease caused by infection of the intestines with the toxin-producing bacterium Vibrio cholerae. The bacteria are typically found in water or food contaminated with the faeces of an infected person. The disease spreads rapidly in areas lacking proper sewage and clean water systems. Infection does not usually occur through direct person-to-person contact, so casual interaction with an infected individual poses little risk. It takes at least a million cholera bacteria to cause infection – yet a single glass of contaminated water can contain up to 200 million, without any change in taste or appearance. This explains why, in the 19th century, long before microscopes were invented, understanding the true cause of outbreaks was exceptionally difficult.

Symptoms of the Disease

Symptoms usually appear 2–3 days after ingestion, though onset can range from a few hours to five days. The bacteria attack the small intestine, triggering rapid loss of body fluids through diarrhoea and vomiting. In severe cases, patients can lose up to 30% of their body weight – equivalent to 20 litres of water. The expelled fluid often contains white flecks from the lining of the small intestine, giving rise to the historic description of “rice-water” stools. In the final stages, muscle cramps occur in the legs and the skin takes on a bluish tint. Without treatment, death can occur within hours of symptom onset.

The primary cause of death in cholera is usually dehydration. With such massive fluid loss, vital organs fail to function correctly. Which organ fails first depends on timing and the individual’s physiology. Today, global mortality rates for cholera infection range from 1.6% to 3.6%. In the 19th century, however, the rates were far higher. In 1854, Soho’s mortality rate reached approximately 12.8%, while other London districts experienced rates as high as 20% during similar outbreaks.

Cholera in London

Cholera was a direct consequence of the Industrial Revolution and the growth of global trade routes. Historical records show no cases of cholera on British soil prior to 1831. Yet the disease had been known at least since 500 BCE, evidenced by Sanskrit records describing its symptoms. For over two millennia, cholera remained largely confined to the Far East.

In the summer of 1831, the disease made it to England by sea and struck the crews of several vessels docked on the River Medway, around 50 kilometres from London. On 8 February 1832, John James became the first recorded Londoner to die from the infection. The first major outbreak in England ended in 1833, claiming over 20,000 lives and forever changing British understanding of this once distant and mysterious disease.

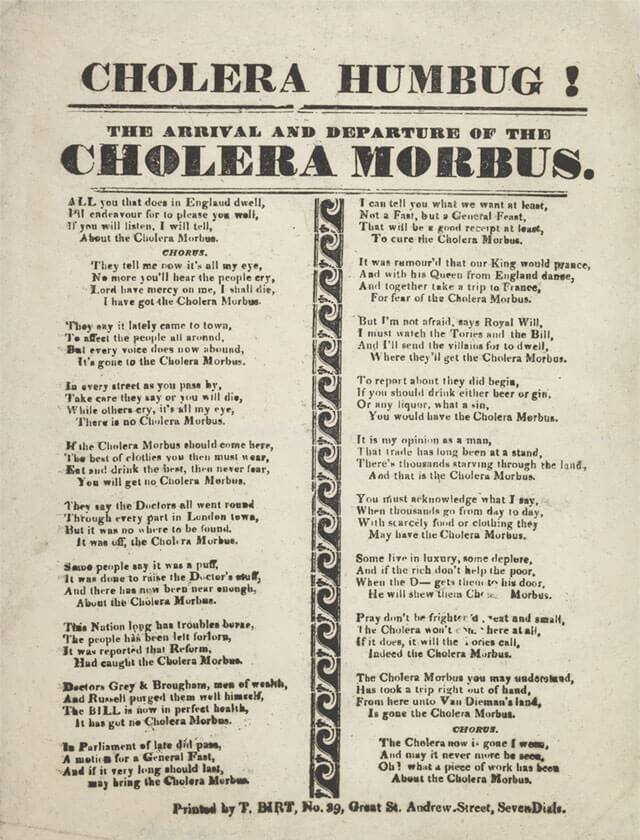

Cholera and the Miasma Theory

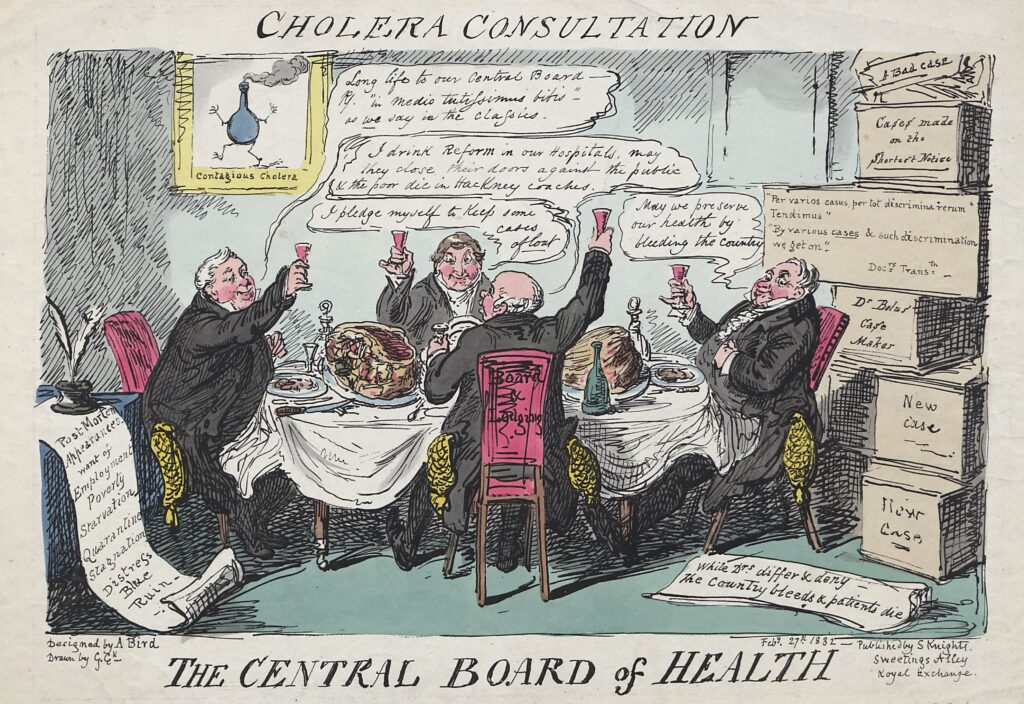

In 19th-century London, countless theories circulated about cholera, each contradicting the others. To contemporary doctors, the idea that microscopic organisms could spread disease through water was as credible as tales of elves. By 1848, the medical world was divided into two main camps: those who believed the disease was transmitted from person to person via an unknown agent, and the adherents of the miasma theory, convinced that cholera arose from poisoned, foul air.

The miasma theory played a pivotal role during the 1854 cholera outbreak, worsening conditions for Soho residents. Most scholars of the time believed that cholera, like plague and other infectious diseases, emanated from miasma – the stinking, corrupted air rising from overcrowded cemeteries, open cesspits, and cellars used as privies. According to contemporary social reformers, the best way to combat epidemics was to purify the air of all foul odours.

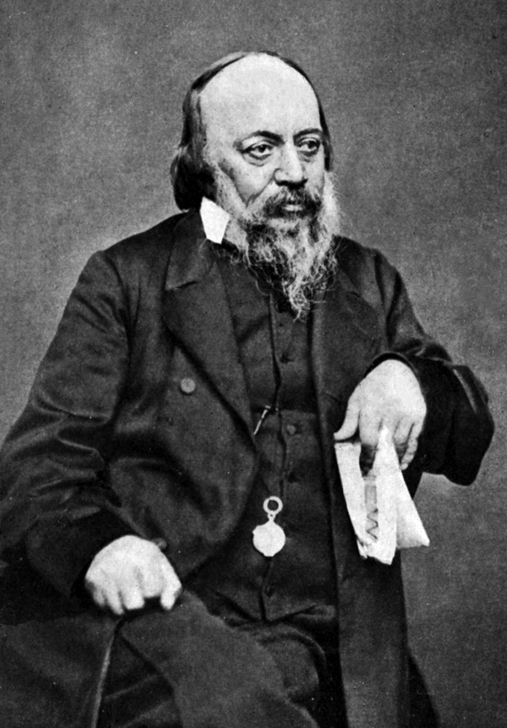

The Reforms of Edwin Chadwick

One of the most influential reformers of the period, who unwittingly contributed to the city’s worsening epidemiological conditions, was Edwin Chadwick. A staunch proponent of the miasma theory, Chadwick focused on improving urban air quality without recognising the potentially harmful effects of his actions. In the 1840s, he introduced a series of reforms aimed at eliminating foul odours from London’s streets. During his six-year tenure at the General Board of Health, over 30,000 cesspits were filled in, and the city’s privies were connected to a new sewer system that emptied directly into the Thames.

Prior to 1815, discharging waste into the city’s main river was prohibited. When a cesspit became full, residents were obliged to summon the “night soil men” to empty it. This outdated system generated a pervasive stench from the occupants’ waste-filled basements – particularly among those who could not afford the service – but it helped to keep the Thames relatively clean.

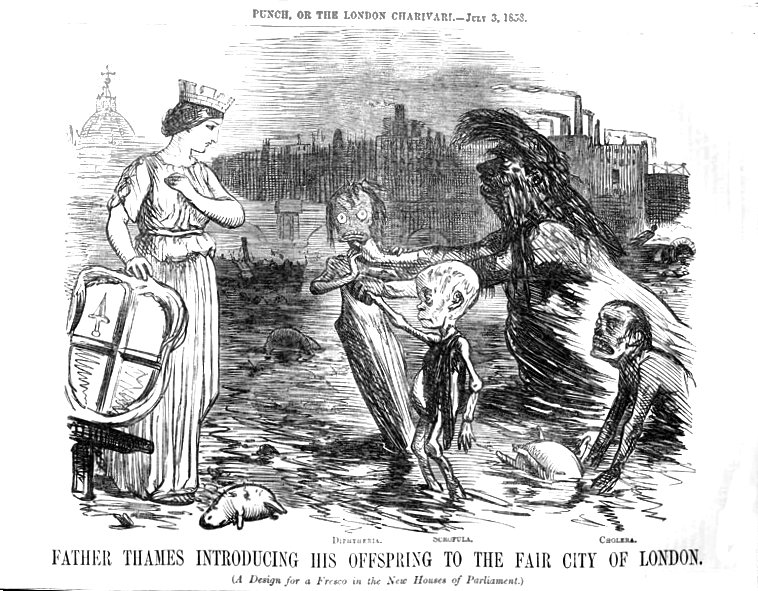

The Thames in Decline

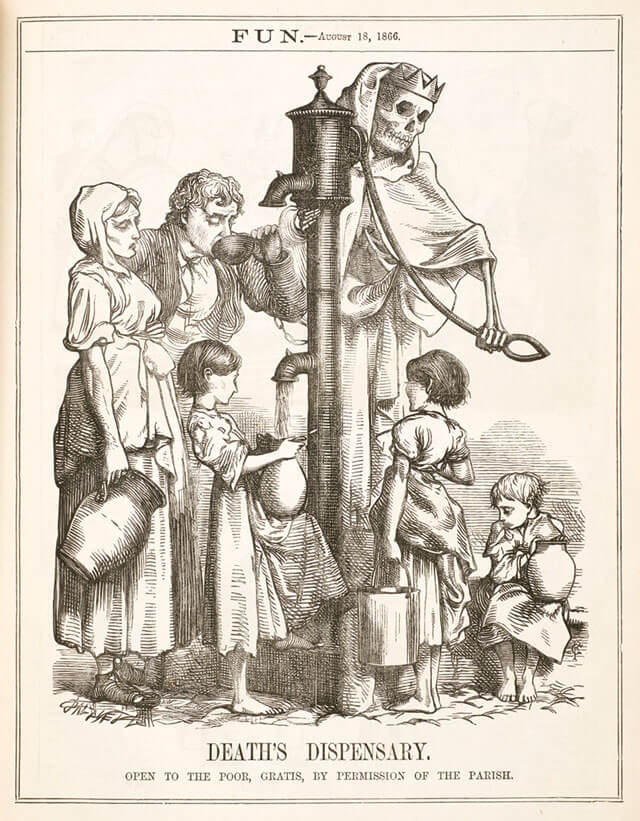

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Thames provided a livelihood for countless fishermen along its entire length, from Greenwich to Putney. Yet over the course of thirty-five years under the rule of miasma theorists, the river was transformed from a salmon-rich waterway into an open, biologically dead sewer — all in the name of public health. Reformers applauded the new sewer system and the “improvement” of urban air, noting spectacular results: 29,000 cubic metres of waste discharged into the Thames in the spring of 1848, and over 80,000 cubic metres the following winter.

The irony of Victorian Britain’s public health system was cruel. In the same city, at the same time, Dr John Snow was developing evidence that cholera was spread through contaminated water, while Edwin Chadwick was building a complex sewer network that delivered cholera directly to Londoners’ drinking water. Residents drew their supply from the very river into which they emptied their excrements. Since the introduction of miasma-driven reforms, cholera returned repeatedly, each time with greater force. During the outbreak of 1848–1849 alone, over 15,000 Londoners perished.

Cholera in Soho

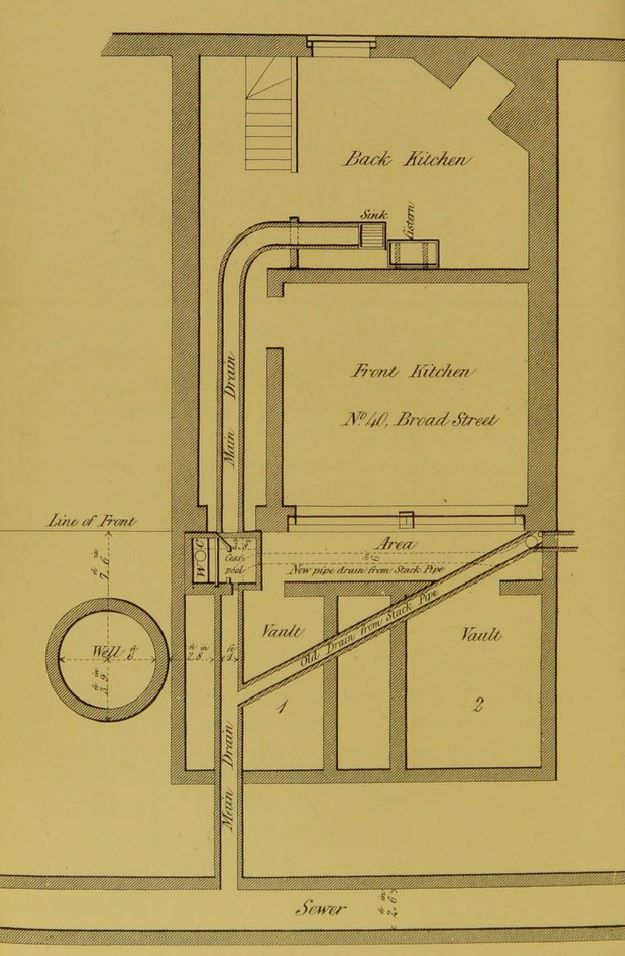

By the late 1840s, Police Constable Thomas Lewis and his wife Sarah had moved into 40 Broad Street. The house, originally designed for a single family, contained eleven rooms now occupied by twenty residents. Thomas and Sarah lived there with their son, who tragically died at ten months. In March 1854, Sarah gave birth to a healthy daughter, who initially seemed more fortunate than her deceased brother. Unfortunately, the mother was unable to breastfeed due to her own health problems and instead fed the child rice and milk from a bottle. The baby remained healthy throughout the summer. How she contracted cholera in August 1854 remains unknown, and her name has been lost to history.

The Outbreak Begins

At the time, cholera outbreaks occurred in London with some regularity, especially in the city’s poorer districts. In the summer of 1854, the disease was concentrated along the south bank of the Thames, and Soho saw only isolated cases. Everything changed on Monday, 28 August.

Around 6 a.m., after an exceptionally hot and sultry night, the Lewises’ infant began vomiting and passing watery, green stools with a pungent, foul odour. Sarah summoned a doctor, who maintained a private practice a few streets away. While waiting for his arrival, she soaked the soiled nappies in a bucket of warm water. In rare moments when the child briefly slept between bouts, Sarah would carry the dirty water outside and pour it into an open cesspit by the garden fence. This simple, tragic act marked the beginning of the outbreak.

The Broad Street Pump

For 48 hours after the Lewis infant fell ill, life around Golden Square carried on as usual. Outside number 40 Broad Street, just a few metres from the sick child, one spot drew a constant stream of passers-by. On that hot summer day, everyone came for one thing – drinking water.

The Broad Street pump had long enjoyed a reputation as a reliable source. Its well reached 7.5 metres deep, placing the water below the level of the waste and filth lurking beneath London’s streets. Many Soho residents who lived nearer pumps on Rupert Street or Little Marlborough Street preferred to walk further for a refreshing drink from Broad Street.

The water was notably cooler than other wells and had a pleasant, slightly effervescent taste. Cafés, sorbet shops, and local pubs all drew from the same source, as did nearby factories filling large barrels for workers. No one suspected that the overflowing cesspit beside number 40, its contaminated contents slowly seeping into the groundwater, could pose any danger.

The Epidemic Unfolds

On Wednesday, a tailor sharing an address with the Lewises began suffering severe stomach pains. By evening, his condition worsened – relentless diarrhoea was accompanied by vomiting, causing a rapid loss of fluids. By Friday morning, his pulse was barely perceptible, his face a bluish hue, and by 1 p.m., he had died. In the following hours, another dozen Soho residents succumbed, while hundreds more experienced their first attacks.

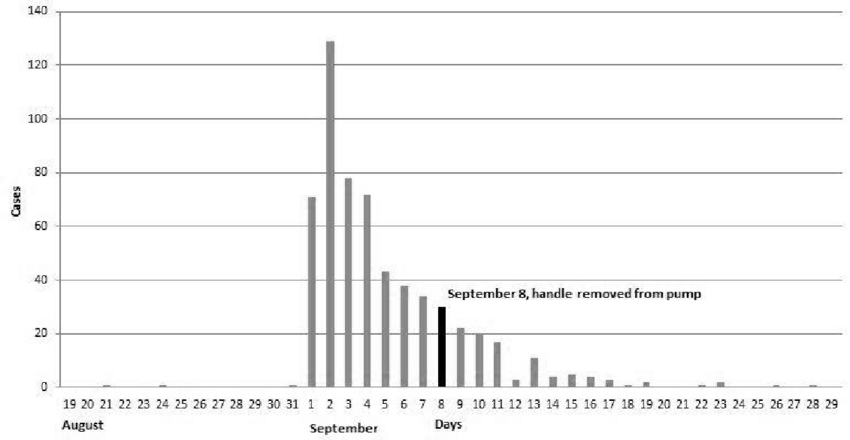

Soho emptied. Many locked themselves indoors – some from illness, others to avoid infection. Half the population fled, leaving homes deserted. By the end of the first week, 70 had died, with hundreds on the brink of death. Normally, cholera in London claimed so many over months; in Soho, one week sufficed. The usual bustle of markets and workshops gave way to a sombre stillness, with priests and doctors racing from house to house. At the mouth of Berwick Street, city authorities raised a yellow flag warning of cholera – a futile gesture when wagons filled with corpses rolled visibly toward cemeteries.

The Peak of the Outbreak

By the second week, a brief relief seemed to emerge. Although the disease still claimed lives swiftly, the pace had slowed compared to the first week. Over five days, more than 500 residents around Golden Square had perished. The General Board of Health sent representatives, including its new chairman, Sir Benjamin Hall, replacing Edwin Chadwick. Their intervention was visible: convinced of the disease’s miasmatic origin, officials ordered all pavements to be drenched in lime chloride. The usual stench of refuse gave way to the acrid smell of bleach.

The True Scale of the Epidemic

Early death counts failed to include those treated in nearby Middlesex Hospital, including many local prostitutes. As patient numbers exceeded Middlesex’s capacity, they were sent to University College Hospital. Westminster Hospital admitted another 80 patients, while St Bartholomew’s bore the heaviest burden – almost 200 admissions in the epidemic’s opening days. The grim events near Golden Square represented only a fraction of the tragedy, and the death toll far exceeded official local records.

Fatalities in Soho continued throughout the following week. By the time the final tally was compiled, the numbers shocked all. Nearly 700 people living within 200 metres of the Broad Street pump had died in under two weeks. Of the 45 houses near the well, only four escaped without loss. While previous London cholera outbreaks had claimed more lives overall, none had killed so many in such a concentrated area, over so short a span.

Dr. John Snow

John Snow was born into a poor working-class family. A quiet and intelligent child, his ambitions far exceeded his humble origins. At the age of 14, he completed an apprenticeship with a surgeon in Newcastle, where he first encountered cholera among miners working in a local pit. The young Snow noticed that the disease might be linked to the fact that the workers ate and defecated in the same cramped quarters.

At 23, Snow moved from northern England to London, where he completed his studies in pharmacy and surgery. Two years later, he opened his first medical practice on Frith Street, just five minutes from Golden Square. In 1843, he passed his final examinations at the University of London, earning his medical degree and gaining access to wealthy patients from aristocratic circles. Yet Snow had no interest in serving the rich or expanding his fortune. He remained in the Soho area, residing in a house on Sackville Street.

By the time of the 1854 cholera outbreak, the 42-year-old doctor had already amassed over a decade of medical experience and was recognised as an outstanding anaesthetist. Snow conducted pioneering research on ether and chloroform and contributed to the design of the first inhaler. He quickly became the city’s most sought-after anaesthetist, assisting in hundreds of operations, including the birth of one of Queen Victoria’s children.

Dr. Snow’s Investigation

Dr. John Snow was convinced that the Soho outbreak stemmed directly from a contaminated water source. He first published his ground-breaking theory on cholera in 1849, but his conclusions were met with scepticism. Miasmatists dismissed his ideas as absurd, and even supporters of contagion theory remained cautious. The medical community largely maintained that, if an external factor indeed caused disease, it would spread through the air rather than being ingested.

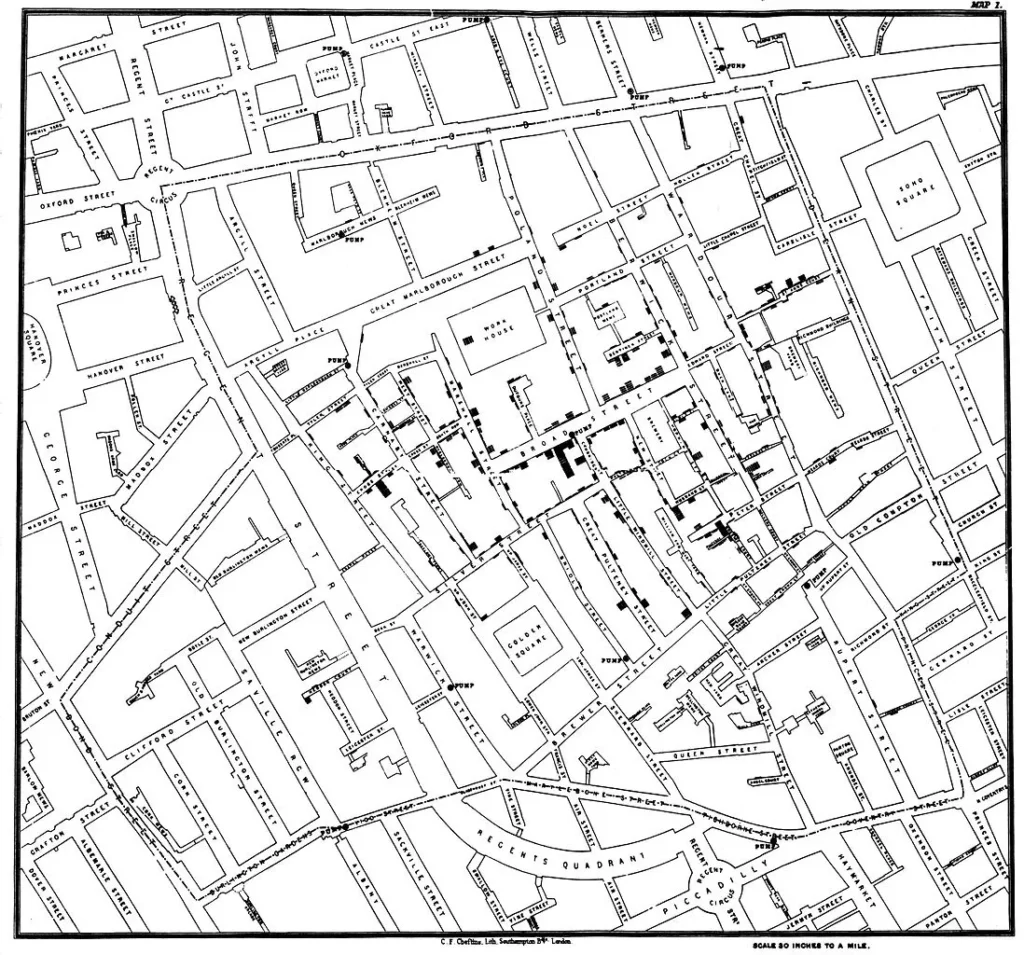

Undeterred, Snow patiently awaited another outbreak to gather more evidence. From the outset, he closely monitored events around the Broad Street pump. Carefully plotting every cholera case in Soho onto a simplified map, he noted a stark concentration of infections around the water source. This unassuming map would later become one of the most important nineteenth-century studies of cholera, reproduced in countless publications.

Father of Epidemiology

In addition to his map, Snow conducted interviews with local residents and discovered that nearly all cholera victims had drunk water from the Broad Street pump. Crucially, he identified a few exceptions, such as a woman from Hampstead who had her sons fetch water from Soho specifically for her. These few anomalies, which clearly linked the victims to the pump, ultimately convinced the medical establishment. The evidence was compelling enough that local authorities removed the pump handle, effectively halting the outbreak.

Snow’s ground-breaking investigation provided key proof that cholera was transmitted via contaminated water. This discovery fundamentally transformed public health strategies and laid the foundation for modern epidemiology. The miasma theory began to crumble, and London adopted a radically new approach to sewage and potable water management.

Discover more from London Macabre

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.